Once the design team has fine-tuned a design that has been more or less quickly approved by management, the mock-up – physical and/or virtual – needs to be transformed into a rolling prototype. The manufacturer then launches a long but imperative test phase to approve the new product. Read more about the ‘overview of the Mercedes design centre in Sindelfingen’ here : https://lignesauto.fr/?p=18876

At Mercedes, in addition to the test tracks on the edge of the Sindelfingen factory and above all those at the new Immendingen test centre (see Bonus 2 at the end of this post), the oldest Mercedes test track still in use is in Stuttgart, in the heart of the Untertürkheim factory and… at the foot of the Mercedes museum.

These Untertürkheim tracks are legendary. They were used in particular for communication following the ABS development tests in the 1970s (see Bonus 1 at the bottom of this post) and for the first passive safety tests under the responsibility of Bela Beranyi. The first phase of construction of the test tracks was completed in 1956, while the proving ground was significantly enlarged in 1967.

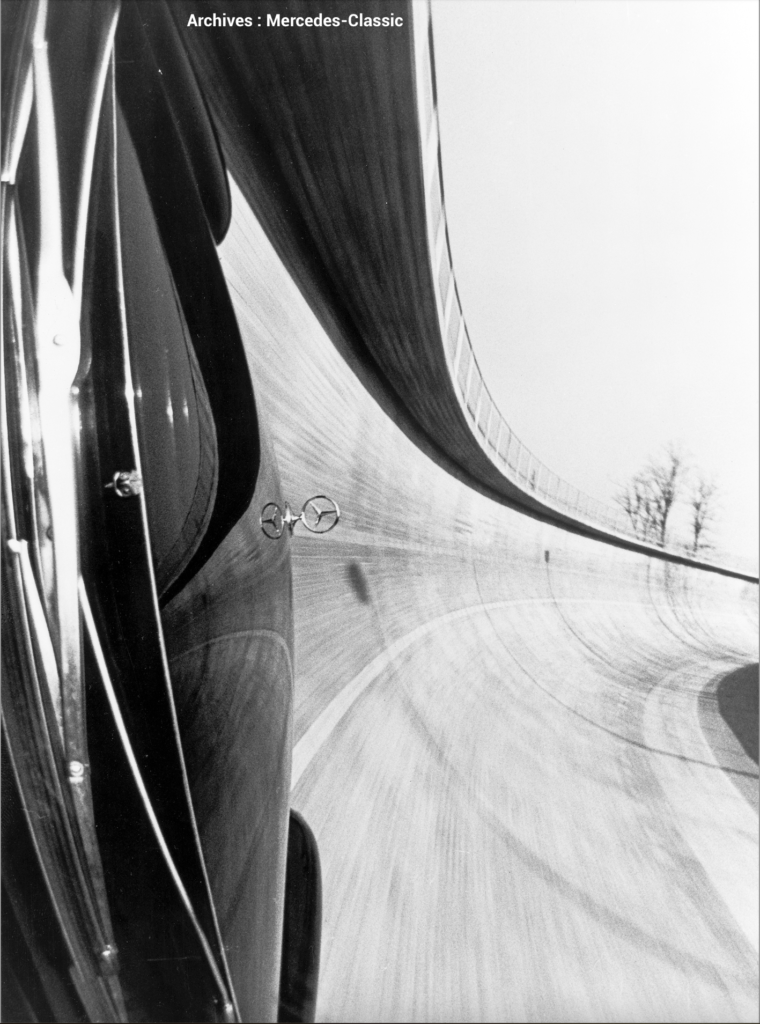

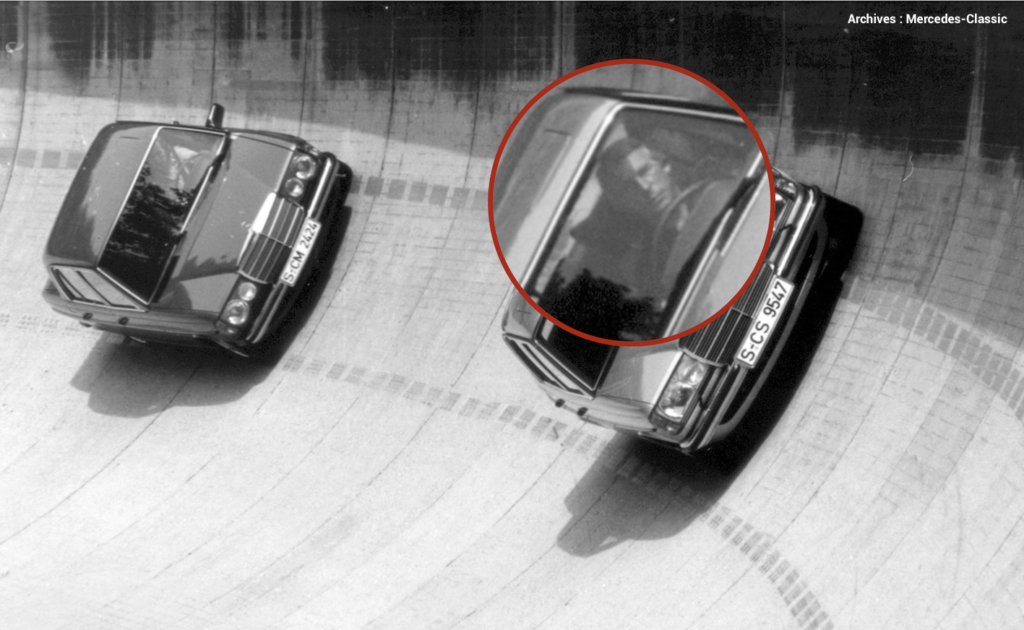

The test tracks adjacent to the Mercedes factory in Untertürkheim total almost 16 kilometres in length, and at the very end of the test site there is still a high-speed section with a very high-speed curve. Its incredible incline is… 90° ! Mercedes was very proud of this curve when it was inaugurated. It’s a curve that we’d like to call the ‘death curve’, even though fortunately no one has ever encountered the reaper on this very special stretch of road.

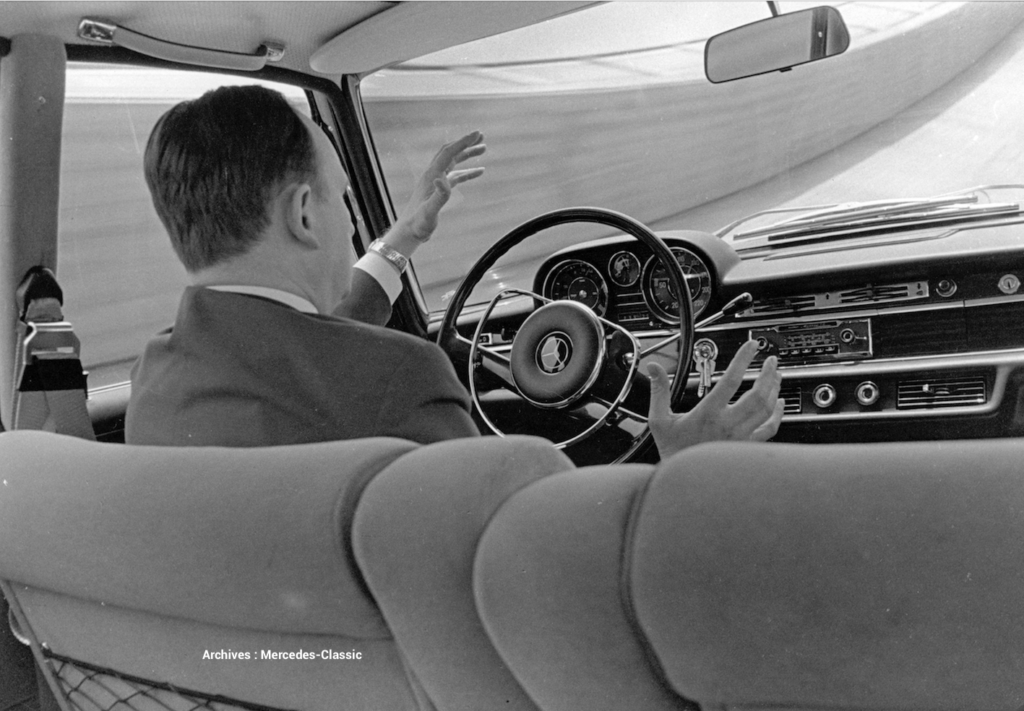

The manufacturer announced at the time that ‘in theory, it can reach speeds of 200 km/h. However, the physical constraints to which the driver and any passengers are subjected limit the speed to 150 km/h.’ The many photos taken ‘in’ this curve testify to the superhuman effort made by the driver to hold his head steady and withstand the totally distorted view through the windscreen, with the huge protective shield at the top that the car sometimes licked!

By 1967, the site had evolved considerably, while remaining constrained on one side by the River Neckar and on the other by the Untertürkheim factory. Caught between water and rail, with a huge marshalling yard on the edge of the site, the tracks are still in use, although those at Immendingen are now operational. Today, you can see part of the Untertürkheim runways from the motorway 14 in Stuttgart below.

So it’s to the famous ‘death curve’ that we turn our attention today. In 1967, the manufacturer’s advertising put it succinctly: ‘The driver of the camouflaged black saloon presses the accelerator once more. He accelerates to 150 km/h and turns into the large curve sheltered by the trees. The curve literally ‘catches’ the car and rotates it along its longitudinal axis in a breathtaking banked position.’

‘It’s as if the horizon suddenly shifted. The driver’s body is pressed into the seat and, from the outside, you can make out the contours of his face. It only takes a few seconds for everything to return to normal: the steep bend brings the car back to level, freeing it on the long straight back to the test site. All the passengers breathed a sigh of relief.‘ You can imagine…

The press was invited to discover these tracks when they were developed at the end of the 1960s. It was one of the brand’s flagships, and it’s worth remembering that they were – and still are! – located in the heart of the factory, a stone’s throw from the fabulous Mercedes museum inaugurated in 2006. At the time, Mercedes explained that ‘rigorous testing of new vehicles is part of the preparation for full-scale production.’

‘These tests are carried out all over the world, not just here. In scorching heat or extreme cold, and in every conceivable environmental condition, the passenger cars and commercial vehicles of tomorrow have to prove their worth on a daily basis. However, it’s not always possible to carry out tests on public roads, particularly in the case of early prototypes. That’s why we’ve had dedicated test tracks at the Untertürkheim plant since 1956.‘

The new test track was presented to the press on 9 May 1967. But people were already asking questions – in fact, my colleagues at the time, because I was only 6 years old and I was storing my Norevs in a herringbone pattern on the chest of drawers in the living room – about this extreme solution of imposing a 90° incline… Mercedes simply replied that this choice was linked to the congestion of the track. ‘It was the solution to the space problems of the old Untertürkheim test track. The test track, which opened in 1956, included a wide range of test facilities, but was too small for high-speed and endurance testing.‘

So, in order to be able to add this type of test, the steep curve was built at the end of an oval extended to a length of three kilometres. Mercedes explained that ‘the previous two-kilometre track has been retained’. A top speed of 200 km/h is theoretically possible in the steep bend, but no test driver could sustain the centrifugal forces exerted on him at that speed over the long term.

As mentioned above, the speed limit was set at 150 km/h from the outset. The guide line painted along the curve, at a distance of 2.50 metres from the outside edge of the track, serves as a marker to be followed at a speed of 150 km/h without using the steering wheel. The angle between the track and the horizon at this point is 71°. The force G exerted on the driver and the car is equal to 3.1 times his weight and that of the car. At a speed of 200 km/h, the driver would be subjected to a force of 5.3 times his own weight… The top of the structure of this curve is 5 m above the ground!

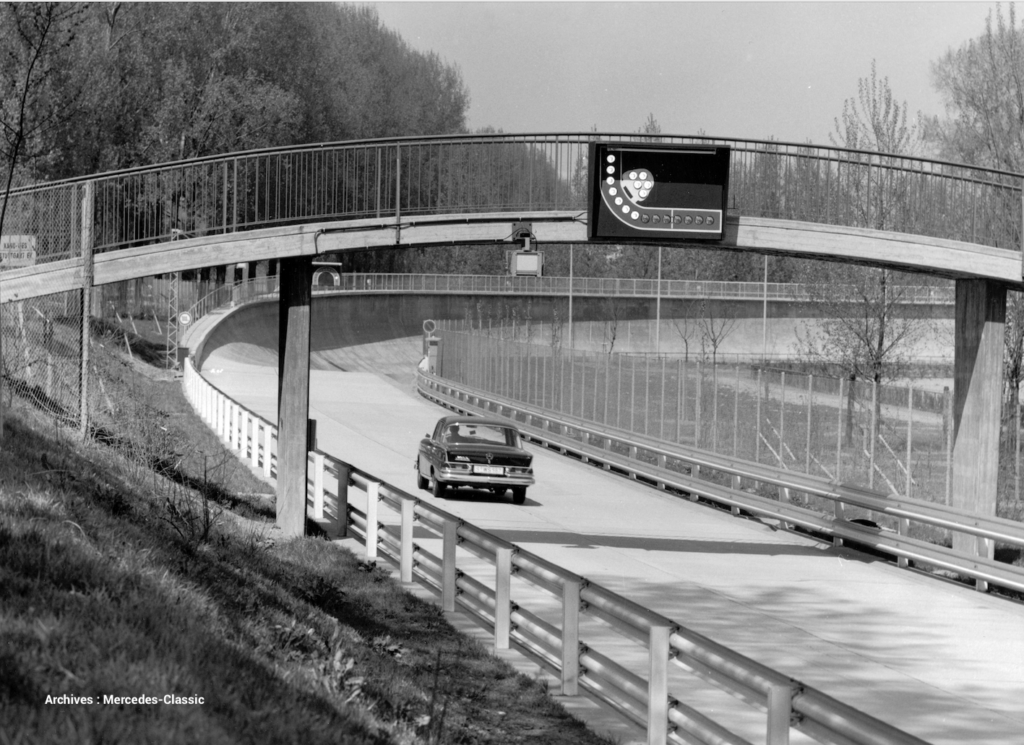

The transition from the relatively flat straight along the Neckar to the crest of the 60-metre-radius curve takes the form of a ‘spiral’, with angles that approach each other as you enter the 90° curve. At the same time as this steeply banked curve, the track was home to a bridge with various ascending and descending ramps, specially built for commercial vehicles, with gradients ranging from 5 to 70%, below, in 1984.

There were also grating tracks, torture tracks and pothole tracks. One of these is a faithful reproduction of a particularly bad stretch of road on the Lüneburg Heath in northern Germany. In order to better understand the level of test driving from the 1960s to the 1990s, Mercedes explained that ‘ each surface is precisely documented and, when a section is damaged by the enormous stresses of test driving, a subcontractor specialising in road surfacing is commissioned to restore it in accordance with the relevant specifications. Fording basins and salt baths for corrosion testing are also available. ’

Apart from the ‘death curve’, the best-known feature of the Untertürkheim tracks is the 100-metre diameter skidpad made up of seven different surfaces: the skidpad, above, in the late 1950s before the motorway was built over it. ‘This track is used for lateral dynamics and powertrain testing,’ Mercedes stated in its press release.

‘The outside lane of the skid track is a steep curve with a 20-degree gradient and allows relatively high speeds. Equipped with all these facilities, the test track represented a major step forward in 1967, as engineers were finally able to carry out series of tests and measurements under identical conditions, as well as taking a test vehicle to its breaking point without serious risk to human beings.’

Another facility was added in 1967: the above fan machine capable of reproducing side winds.No fewer than 16 powerful wind tunnels were installed to simulate and accurately measure the deviation of the prototype in these conditions, which we all encounter on motorways when overtaking lorries, for example. But these test tracks are not just external: test benches measuring exhaust gases were set up at Untertürkheim in response to the first emissions laws that came into force in California in the 1960s. Compliance with these laws was obviously a prerequisite for exporting to the United States.

In the end, since its development in 1967, the test tracks, which have a footprint of 8.4 hectares, have proved their worth in this configuration. There have been no major modifications since 1967, with the exception of a section of road with tram tracks, a common feature in Germany in the 1960s. This section of road was subsequently transformed into a smooth section of road with a quiet asphalt surface for noise measurements.

The brand new tracks at Immendingen have certainly largely supplanted those at Untertürkheim and Sindelfingen, without killing them off, quite the contrary. It should be added that the Stuttgart-Untertürkheim site enabled test drivers to cover around two million kilometres a year on tracks with an average of 750 cars, which in the end represented only a fraction of the 20 million kilometres covered each year as part of the car tests that are also carried out on ordinary roads.

Today, digital testing has shattered some of these tests. A small part or a large part? It varies from one car group to another. Here we must salute Mercedes, which has kept its Untertürkheim and Sindelfingen test tracks alongside its brand new Immendingen test site, while at the same time Stellantis sold its exceptional site and legendary test tracks at La Ferté Vidame this year…

The straight today runs alongside the river Neckar and at the end, the finish on the ‘death curve’. The vegetation has re-grown a little…

Bonus 1

Untertürkheim and ABS

The ABS braking system was first launched in 1978 by Mercedes in partnership with equipment manufacturer Bosch. This anti-lock braking system was unveiled from 22 to 25 August 1978 on the test track at the Untertürkheim plant. ABS was offered on the S-Class (116 series) from the end of 1978. This development was also the starting point for a unique history of innovation in digital assistance systems. It should be remembered that this system makes it possible to retain total control of the car’s steering, even in the event of emergency braking, since it prevents the car from locking up.

Order the bilingual LIGNES/auto #05 mook dedicated to Mercedes here: https://lignesautoeditions.fr/?p=790

Bonus 2

The new Immendingen test site

Mercedes has invested over €200 million in the Immendingen test site located around 130 kilometres south of Stuttgart, which has been operational since September 2018. This site, which enjoys absolute discretion where it is perched (!), enables ALL vehicle testing worldwide to be concentrated on a single site. Mercedes points out that ‘ Immendingen plays a key role in the development of the mobility of the future: it is here that all vehicle tests on a global scale are consolidated, including the development of other types of hybrid and electric drive systems under the EQ product and technology label. Future assistance systems and autonomous driving functions are also tested here ‘. This test and technology centre took more than three years to build in Baden-Württemberg.

‘Narrow roads like in the Alps, wide multi-lane motorways like in North America, tedious traffic like in a southern European city: many traffic situations can be realistically simulated on the site. In the process, we see time and again that reality always holds surprises that the computer hasn’t taken into account‘, says Reiner Imdahl, who heads up the site. This gigantic testing ground was built on a former training ground belonging to the German army. When the route was laid out, the impressive topography with its different levels and altitudes ranging from 660 to 880 metres above sea level was exploited to the full for the countless road tests.

For completeness, below are the test tracks at the Sindelfingen industrial site, very similar to those at the Untertürkheim plant. In 1, the factory and in 2, the tracks with a raised curve – but not as high as the ‘death curve’ – where you can also make out the presence of a Skidpad.