In the mid-1960s, two programmes took shape in Citroën’s design offices. Both concerned the DS. The first was to breathe new life into the 1955 saloon by refining its modern, powerful engines. There were also plans for an aesthetic refresh which, surprisingly, mainly concerned the rear of the car, although it was ultimately the front that was radically changed in 1967, for the 1968 model year, with its famous rotating headlights.

The second had more distant ambitions and imagined what the large Citroën saloon of the 1970-1980s would be like. This was the ‘L’ project. While Pierre Bercot gave complete freedom to the creative team led by Robert Orpon, Citroën’s styling director since 1964, the brand’s management, with Raymond Ravenel and Claude Alain Sarre in particular, seemed much more reserved.

According to these two men, the ‘L’ should be a sensible three-seater saloon with a boot, to appeal to a wider customer base than the DS. As early as 1969, the first projects were sketched out. Opron’s loyal customers could be counted on practically the fingers of one hand. There was, of course, Henri Dargent, who had been responsible for styling under Bertoni in 1957. Jacques Charreton, Régis Gromik and Jean Giret, the sculptor with the golden hands, complete the team with Michel Harmand, the man of art.

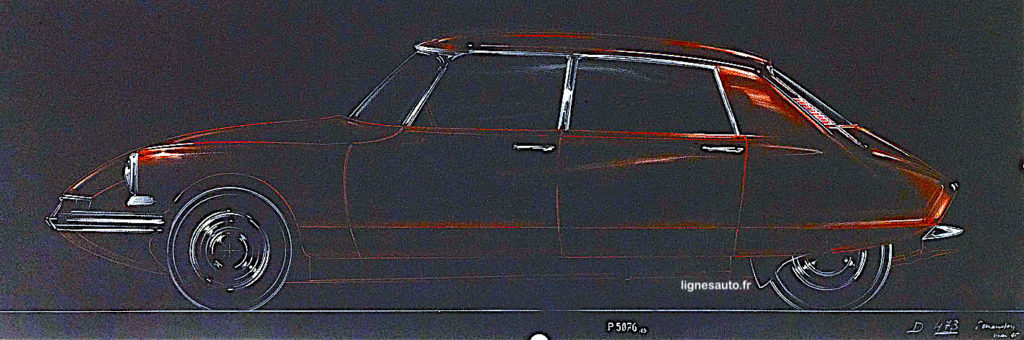

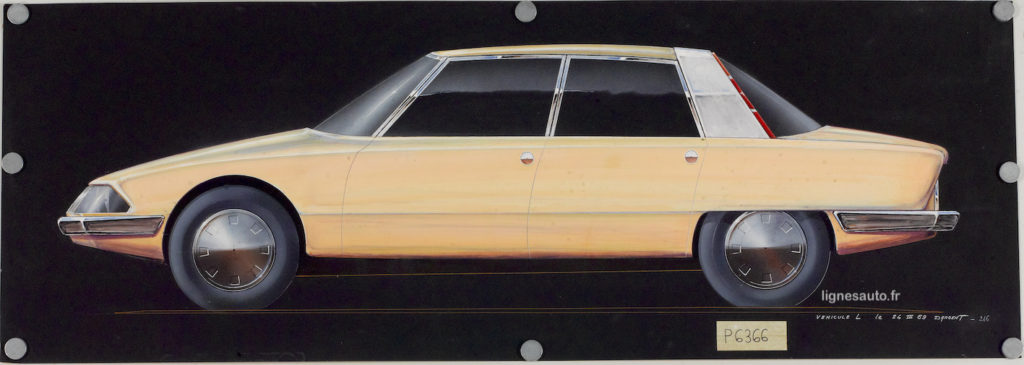

Henry de Ségur Lauve, an American, was added to the team during the holidays (!). He would remain so until the arrival of Peugeot in 1974. They all set to work, and Robert Opron, in order to be left in peace at the top, decided to satisfy both camps by simultaneously launching a classic project and another with the brand’s innovative DNA. It’s some of these early projects, produced solely in the form of drawings, that we invite you to rediscover today. Firstly, the visions of a classic three-box, as imagined by Henri Dargent and Michel Harmand.

And to think that the CX could have been this classic, ancestral saloon! Then came the search for a hatchback capable of satisfying both Raymond Ravenel’s desire for classicism and Pierre Bercot’s demand for originality.

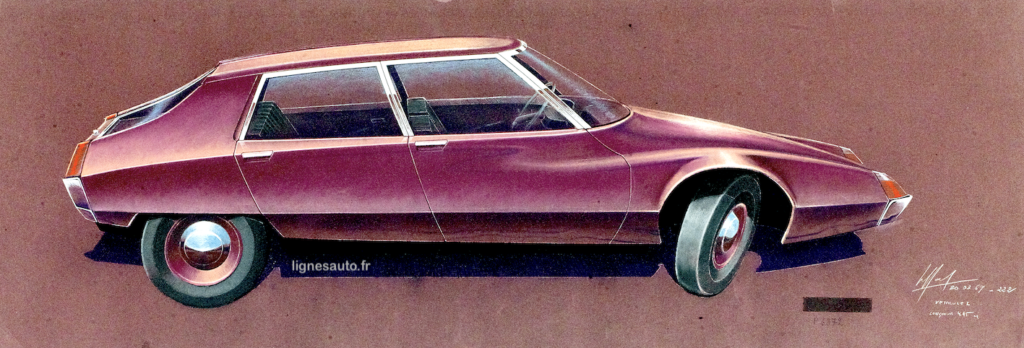

Henry de Ségur Lauve came up with these strange, slightly American silhouettes. At the time, there was no customer or competitor analysis department. Robert Opron didn’t care, and worked on instinct, even if his GS (1970) and CX (1974) bore a strong resemblance to the Pininfarina BLMC concepts of 1967 and 1968…

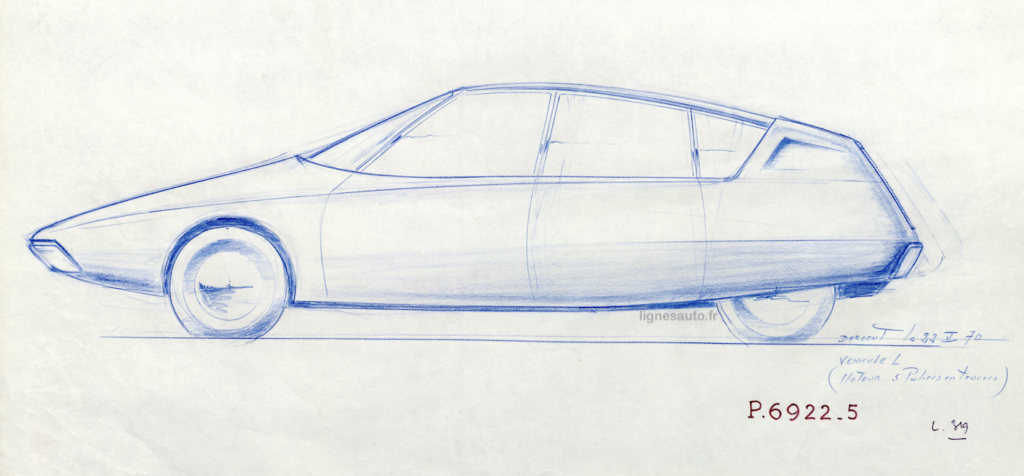

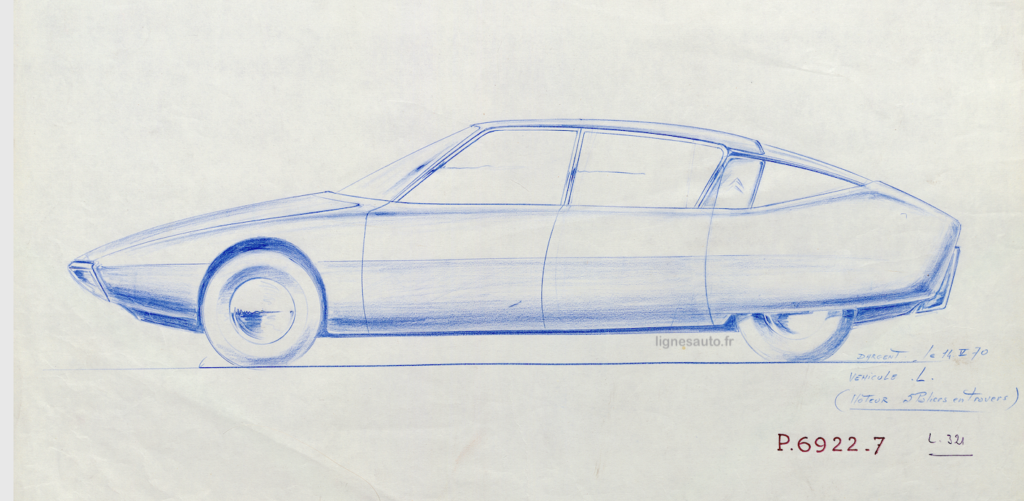

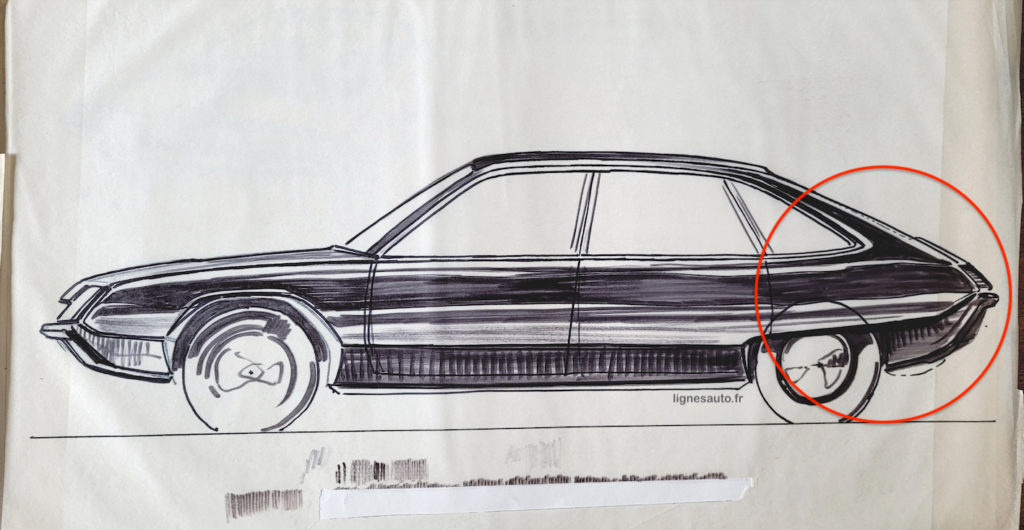

Henri Dargent, for his part, offered a number of drawings of hatchback versions, one of which, below, begins to lay the foundations for the stylistic architecture of the future CX. The two sketches date from May 1970 and the designer specifies that the engine is “positioned across the body”.

At the first major meeting with Citroën management to decide on the styling theme for the saloon that was to become the future DS, Robert Opron first unveiled a mock-up of a classic, well-balanced model with a well-integrated boot lid and a slightly pretentious stature. Ravenel liked this proposal. Bercot did not. Bercot was then led by Opron behind a screen where, under a tarpaulin, was hidden the model of an elegant, aerodynamic saloon… two volumes.

The CX was in its infancy at the time, but it immediately won over the big boss. Robert Opron was relieved and amused by his feint. Work could begin on refining the styling of what would become the CX four years later…

BONUS NO. 1: WHAT NEXT?

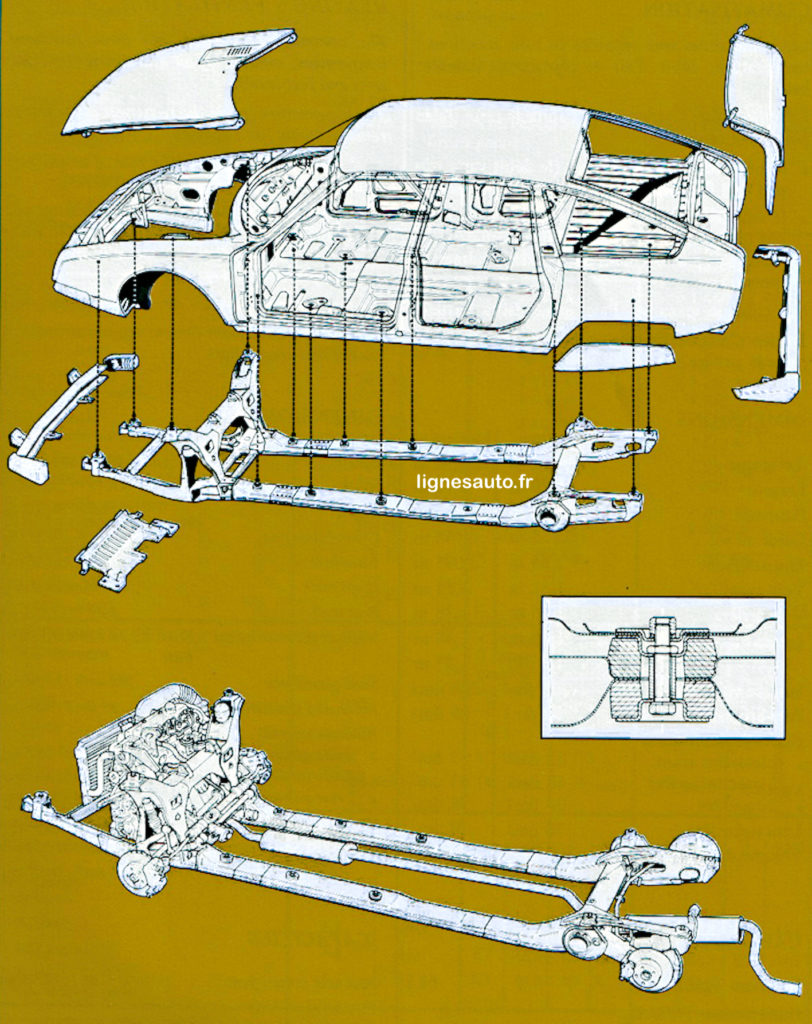

As always with Citroën, design is only part of the product revolution. For the CX, the hydraulics are still present, but the large saloon also offers an architecture with a ‘false’ chassis on which the monocoque rests for greater comfort and soundproofing.

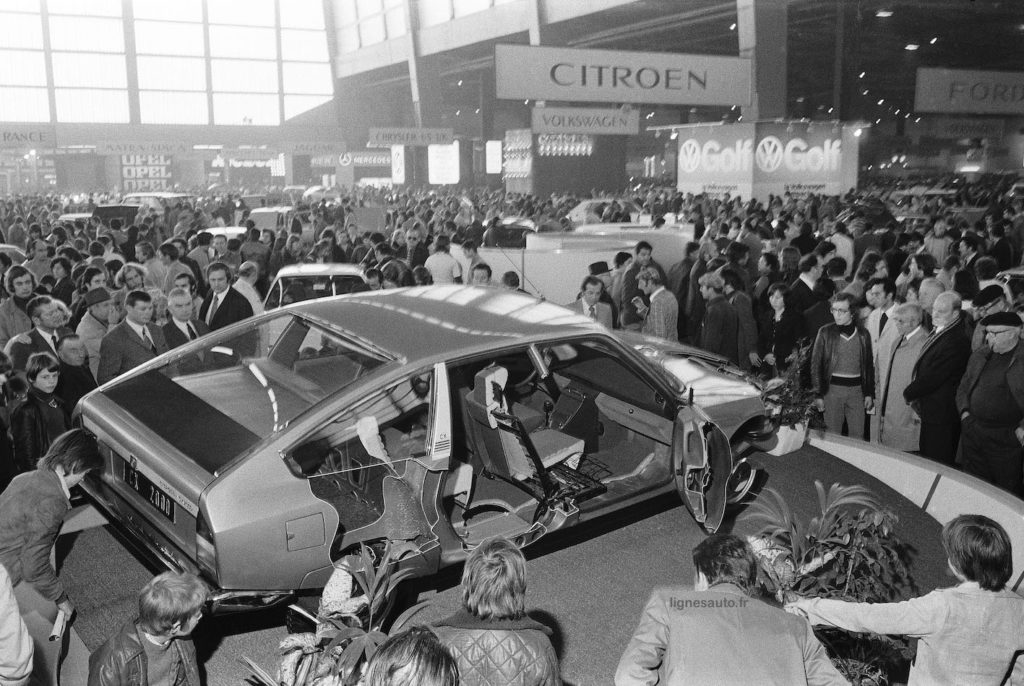

The 1974 Paris Motor Show provided an opportunity to discover the two versions of the CX: CX 2000 (1,985 cm3, carburettor, 102 bhp) and 2200 (2,175 cm3 carburettor, 112 bhp). Contrary to what was planned at the outset of the ‘L’ project, the Wankel rotary piston engine is not on the programme. Two variants were planned: a 110bhp 995cc twin-turbo (the same as on the GS Birotor) and a 160bhp 1.5-litre triple-turbo.

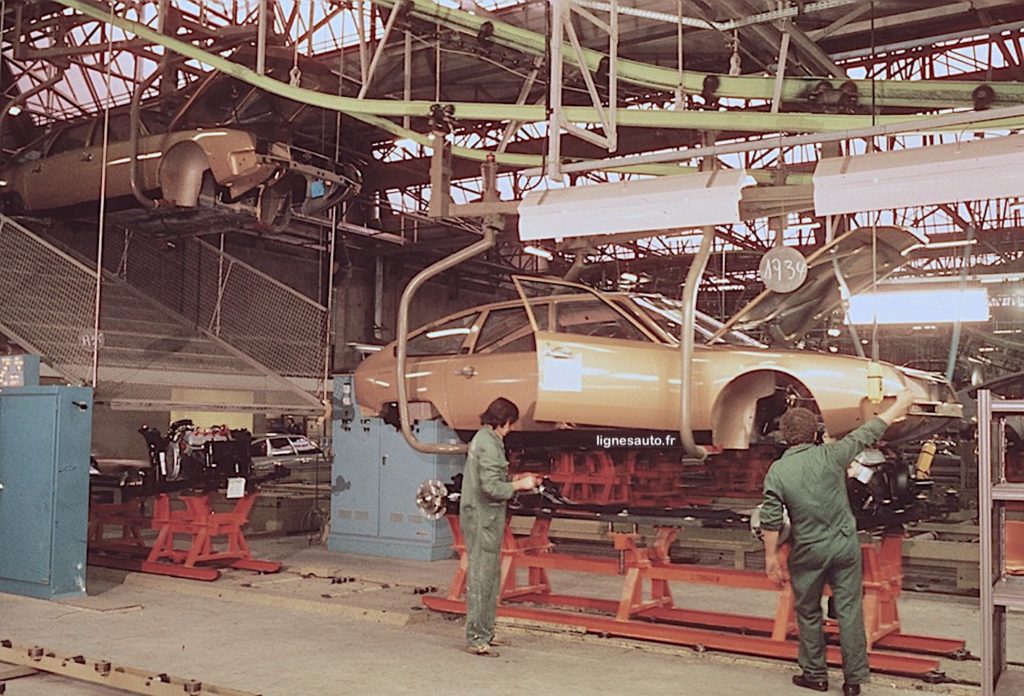

Above, press tests of the CX are taking place in Lapland, while at the same time, the production rate at the Aulnay-sous-Bois plant is increasing: this industrial site has been designed and built for the new queen of the road!

Below, the spirit of the CX will be reborn at the 1999 Geneva Motor Show with the C-Lignage concept car designed by Marc Pinson. The latter was trained by the master Michel Harmand, and the concept of the original saloon was respected. The production C6, closely based on this concept car, was produced from 2005.

The CX continues to inspire the brand’s designers. In 2016, the CXpérience concept car (pictured below) was unveiled at the Paris Motor Show. It was designed by Grégory Blanchet and the interior by Jérémy Lebonnois.

BONUS NO. 2: WHEN THE CX WAS (ALMOST) A RENAULT 30!

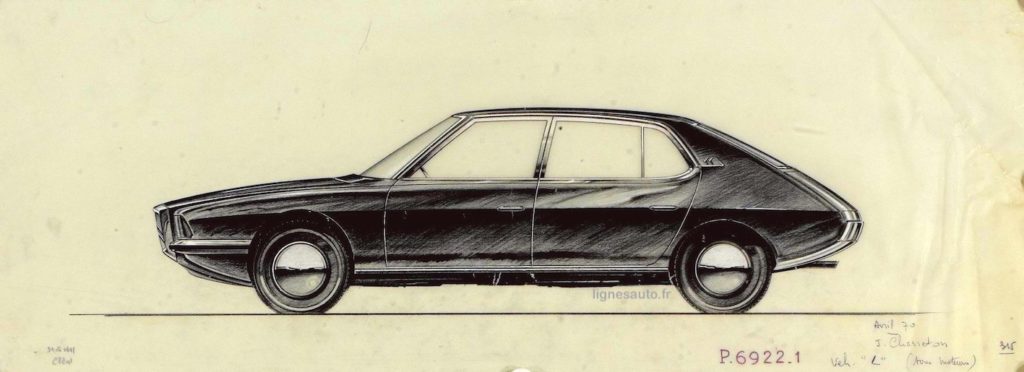

In April 1970, stylist Jacques Charreton of the team led by Robert Opron proposed this design (above) for the ‘L’ project of the future CX. In the end, a strict hatchback with a rather compact rear end was chosen, far removed from the slender profile. But this elevation view is reminiscent of a rival Renault project: project 120 studied in 1968, as can be seen from the profile below taken from the archives of Gaston Juchet, then head of Renault styling.

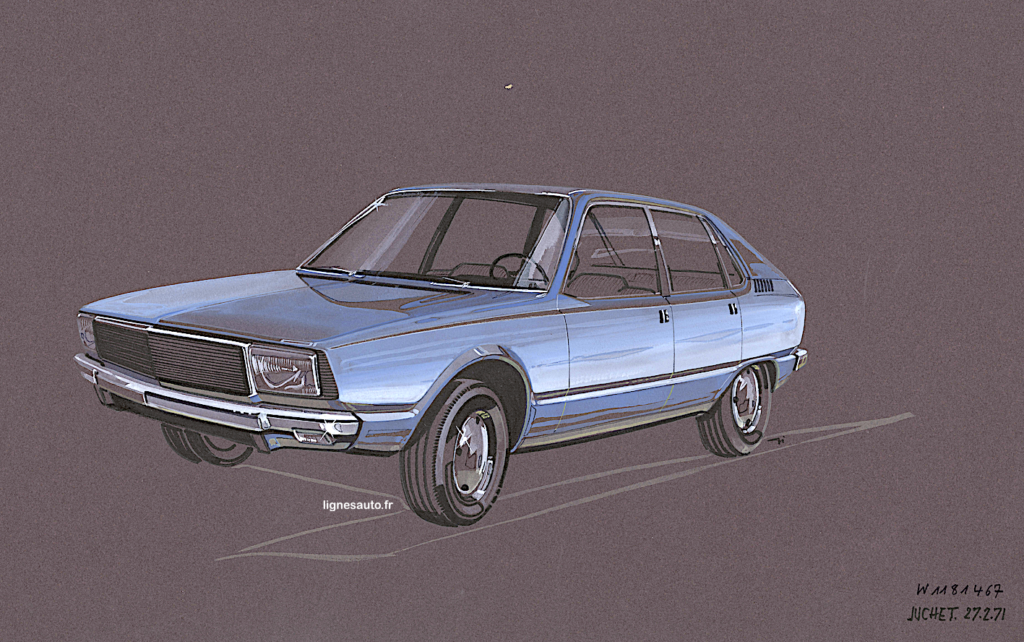

This Renault 120 project evolved into project 127 and gave birth to the Renault 30 in 1975, the same year that the Citroën CX came onto the market. It was carried out at virtually the same time as the big Citroën, as can be seen from the date of creation of the R30 drawing below: February 1971. Gaston Juchet, head of Renault design (he would be supervised in 1975 by… Robert Opron, who left Citroën to avoid working with the Peugeots following the creation of the PSA group) continued to study the 127, and his project was finally selected.

To find out everything you need to know about the Gaston Juchet era at Renault, from 1960 to 1987, read the bilingual book dedicated to him, which won the “Grand Prix du livre Historique 2023”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9veCCVXckE