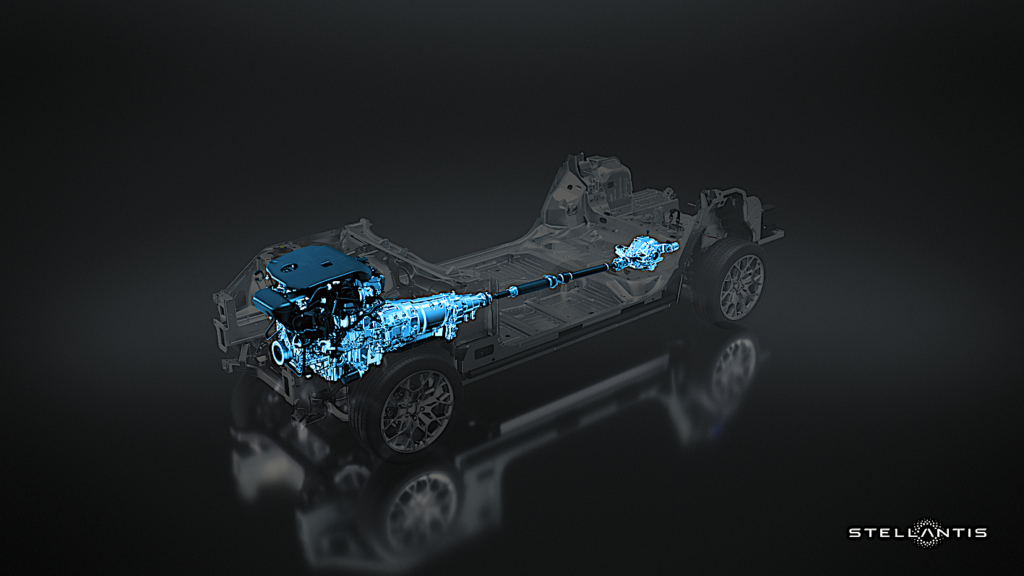

Have the majority of designers on the automotive planet been betrayed by the mirage of the electric platform? A chimera into which they plunged with delight and envy. The electric platform was sold to them as inventive, because it is freed from the cumbersome combustion engine powertrain (engine, gearbox, exhaust system, fuel tank, etc.) and from the invasive crash-test structures required by the powertrains of ” life before “.

The electric platform is the Holy Grail: a small motor at the front, or even at the rear – or even two compact electric motors -, control electronics and a battery pack housed flat in the floor. The icing on the cake is that exterior designers can play around with large wheels at all four corners, always a pleasing way of magnifying proportions, and putting an end to ‘Cyrano de Bergerac’-style overhangs. Their interior design counterparts can revel in the flat floor, the reinvigorated space on board thanks to the relocation of the air conditioning to the front end, and the ever-slimmer, if ever-more-present screens. In short, customers were in for a real treat, and design enthusiasts were expecting a veritable revolution in concepts, proportions and silhouettes.

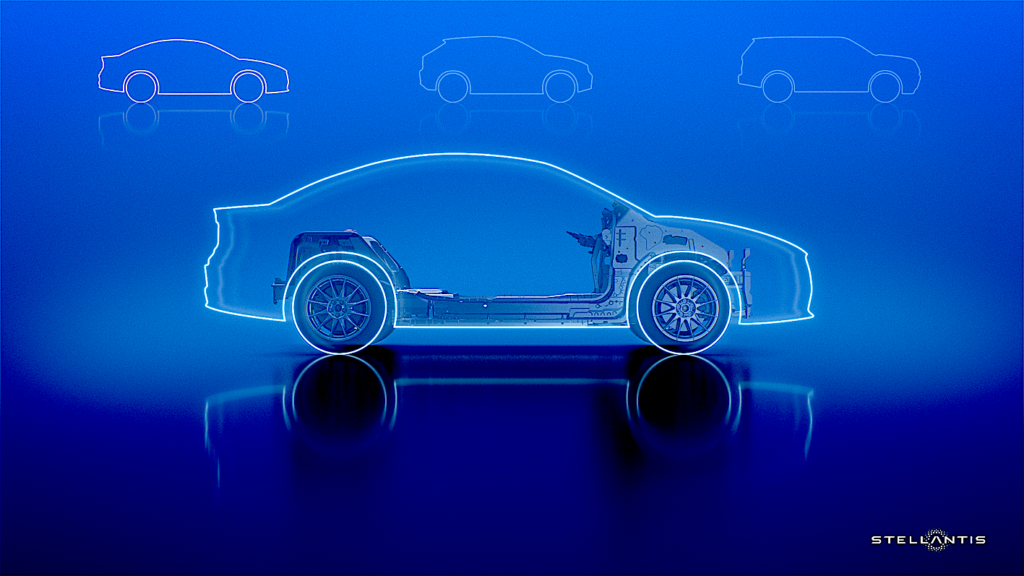

Patatras. Nothing of the sort, because the designers were somewhat betrayed by this mirific scenario. Take the example of Stellantis and the new Alfa Romeo Milano above (it will be presented on 10 April) with the Peugeot 2008. It is striking to note that the Italian manufacturer’s designers did not have the opportunity to modify the structural architecture of the ‘source car’, the Peugeot 2008. The same applies to the new Lancia Ypsilon in relation to its Opel Corsa and Peugeot 208 cousins, the latter also playing the role of ‘source car’.

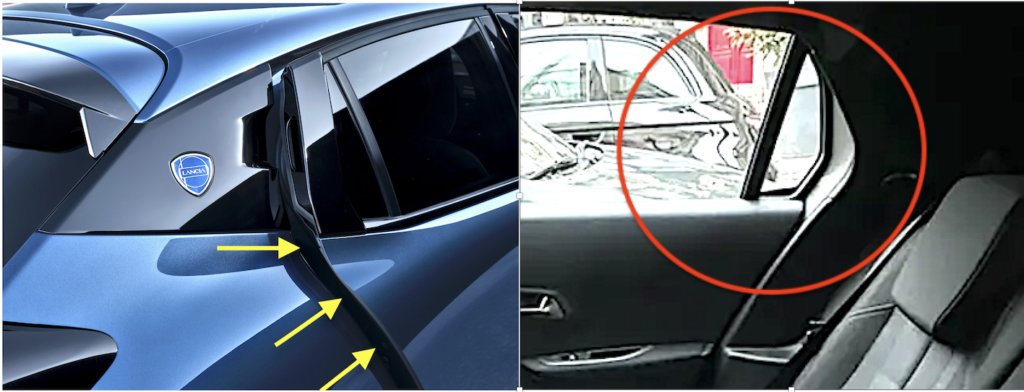

We’re not just talking about their electric motors or their underpinnings, but many other structural elements that have a direct impact on design. The problem for designers is well known: it’s called ‘ carry over ‘, or to put it more clearly, the recovery of as many common parts as possible between models in the same segment but from different brands within the same automotive group. At Stellantis, the ‘carry over’ often includes the recovery of the front end, the windscreen bay, the technical canopy and the windscreen itself. Add to this the ‘hard’ (untouchable) points of the structure at the level of the heads of the passengers in row 2 and the hinges of the tailgate, and you will understand that the latitudes offered to the designer to dare new silhouettes are limited.

The designers will tell you hand on heart that this “carry over” is, on the contrary, a rich source of creativity. Backstage, when the tape recorder cuts out, they will tell you that, yes, it is extremely restrictive. To take away their desire to create new concepts for good, you also have to add the doorway to the ” carry over ” basket. This is what you see when you open the door and discover a complex structure with, in particular, this black seal that follows the contour. Carrying over all or part of this structure is more than a constraint for the designer, it’s a prohibition on him generating modifications in this complicated and structuring area. He is therefore confined to designing a skin with predefined contours.

In short, there is no longer any question of differentiating the architectural concept of an Opel from that of a Peugeot or a future Lancia, other than by retouching the vehicle’s skin. Of course, there will be a legitimate argument that not all manufacturers are in the same boat. Volkswagen did not wait for the all-electric euphoria to set in motion its ‘copy-paste’ machine between the Volkswagen, Audi or Skoda brands, in the internal combustion era. Except that the context is no longer the same. With the electric architecture, the platforms offer new horizons which even Volkswagen has seized by differentiating its internal combustion vehicles from its electric vehicles. And for the latter, the Volkswagen Group’s former head of design, Klaus Zyciora, dared to come up with concepts – alas, not very innovative ones – such as the almost one-box ID.3.

What’s more, the Volkswagen group doesn’t have fourteen brands to manage, which is a complication for the Stellantis group with its various divisions. The fact that a Peugeot 208 was chosen at the time as the basis for the Corsa can be explained by the time needed to create it: it had to be done quickly. It’s a much harder pill to swallow when it comes to the revival of the Lancia brand, with a Ypsilon that could have – and should have? – had been given more freedom and boldness in its concept, by leaving the designers free rein in terms of structure. But this would have meant abandoning the pooling of components, investing in new parts and drastically reducing the famous ‘ carry-over’. And, by the same token, reduce the double-digit profitability that is the foundation of the Stellantis Group’s economic success.

Carry-over is one of the keys to the profitability of a project, whether managed by Stellantis, Volkswagen or Renault. In the case of the latter, for example, the R5 E-Tech will lend all its interior furnishings to the next R4 and R4 Van, to ensure a more definite, and even rapid, return on investment. The same applies to the next DS (project D85 below), which will be produced in Italy at the Melfi plant and will lend its platform to the next Lancia Gamma in 2026, which will also be produced at this plant. This Stellantis STLA Medium platform, which has been used by the Peugeot 3008, will impose some of this ‘carry over’ on its two Franco-Italian cousins. And if we look even further ahead, what can we expect from the next generation DS4 compared with the Lancia Delta of 2028? Will it share many of the same structural components that restrict designers’ creativity?

We write that ‘ carry over ‘ is one of the keys to Stellantis’ economic success. Yes, this is true, and it is to the credit of a boss, Carlos Tavares, but also of all the employees concerned working for Stellantis. But just how far should we push the boundaries of this community of parts, particularly structural parts, which make those responsible for managing tomorrow’s product plans pull their hair out? The brands in Stellantis’ Premium division (Alfa Romeo, DS Automobiles and Lancia) have a soul, like so many others. And a soul is hardly compatible with the idea of excessive pooling. What can we say about Lancia which, unlike Alfa Romeo, is having to rebuild itself from almost nothing: a Ypsilon hitherto sold only in Italy. Like Lancia, DS is currently targeting the European market and, unlike its two rivals in the Premium segment, has no history. Or very little: just 10 years.

Ferdinand Piëch gave Audi 30 years to become Premium, so let’s give the DS brand the time it doesn’t have! Rival Alpine, with its aggressive product plan (which includes crossovers that will compete with future DS models) and its American ambitions, has no intention of waiting for DS to finally make its move! An Alpine will never resemble a Renault or a Dacia from the same group. It’s not certain that this will be the case with the future compact cars from Stellantis’ Premium group, Alfa-Romeo, DS and Lancia… The Alpine brand can also draw on Renault Group platforms, but it has just demonstrated that the Group has also given it the means to create its own platform dedicated to the future A110, A110 Roadster and A310 sports silhouettes.

What’s more, DS Automobiles has yet to market a sports silhouette, despite the fact that many of its concept cars have such genes, and that the brand is present in the 100% electric Formula-E world championship. Which is a bit rich, at a time when DS Automobiles is moving towards all-electricity! Is it just because the existing platforms are not capable of it? We doubt it… The answer undoubtedly lies in this famous double-digit profitability. But DS will have an advantage: this year, it will unveil its D85 project for a crossover saloon of fairly generous size, before Lancia does the same with its similar project in two years’ time, the Gamma. Will this leadership bonus be enough? And for the record, one of DS Automobiles’ master designers (Ugo Spagnolo) joined… Lancia some three years ago. So let’s keep it in the family!

Today, Stellantis is working on the various product plans for its many brands with its platforms, which should be ‘e-native’, i.e. designed for 100% electric power. The STLA Medium platform inaugurated by the Peugeot 3008 and the STLA Large unveiled earlier this year are both capable of carrying combustion, hybrid or 100% electric powertrains. This could be an advantage if legislation in Europe – and the United States – shifts towards 100% electric vehicles in the future. For the time being, the new models are suffering from the disadvantages of this multi-energy choice: weight, overhang, space-length ratio.

The example of the Peugeot e-3008 compared with the Renault Scénic (below), designed on a platform entirely dedicated to 100% electric power, speaks for itself: shorter, with just as much interior space and much lighter, the Renault beats the Peugeot in certain areas of the game. But unlike the 3008, the Scénic won’t be able to change its tune if the all-electric wind shifts. Renault does, however, offer its own hybrid internal combustion models. The Losange is no fool either. Two strategies, two management models for a future that is not yet fully defined at regulatory level… As we have seen, with 14 brands, four platforms and a formidable ‘carry over’ imposed, the people who manage the product plan for each of the Stellantis group’s labels have their work cut out for them! Of course, architects can play around with wheelbase ‘steps’ (around 5 to 6 cm more or less for each ‘step’ on the same platform) or track width, not to mention wheel size.

But, for each of the four platforms, with common windscreens, common awnings, common row 2 passenger compartments, common front ends, etc., the designer sometimes (often?) finds himself with a limited range of creativity. Fortunately, as head of design for the Stellantis Group’s European brands, Jean-Pierre Ploué (below) has mastered the manifestos of each of the brands, which set out their own stylistic language, the reference colours for each of them, their graphic language and the whole context of creation and communication. But is this enough now that the game has changed: four platforms and the virtual impossibility of modifying those famous hard points that determine the strength of a design?

Given this situation, it is to be feared that there will be fewer and fewer silhouettes, shrinking the Group’s offering. What will become of the soul of these brands? Faced with the forthcoming DS 4 and Lancia Delta, which embody French luxury in the case of the former, and the Italian touch in the case of the latter, what will be the criteria for choice other than on-board materials if the two silhouettes are identical in their proportions and concept? Style, and style alone?

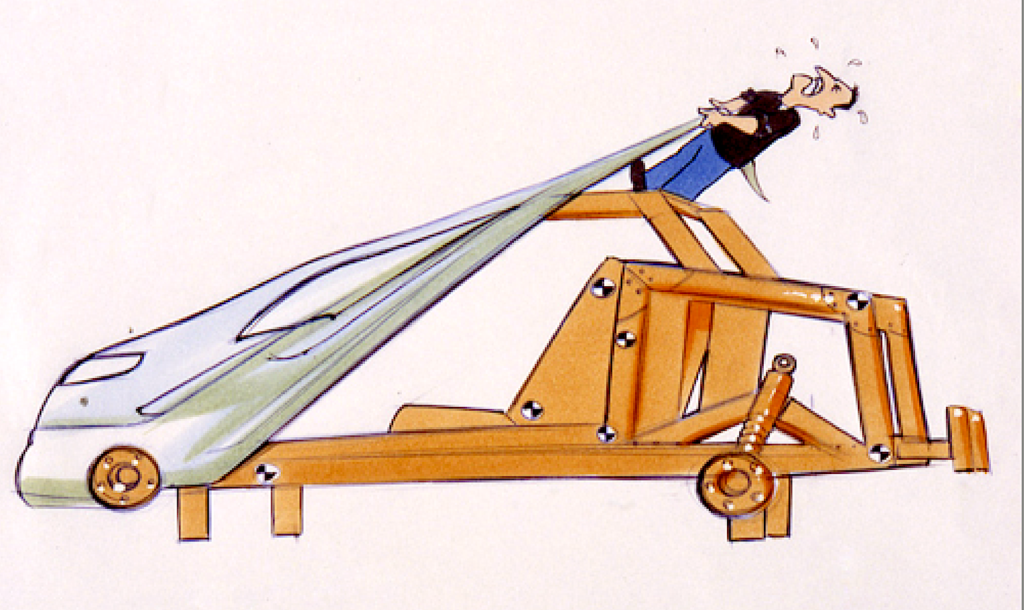

It is incredible that, with the arrival of electric platforms, today’s designers are all too often faced with such constraints. In 2024, many of them have fallen back to a time when the stylist was content to ” dress the hunchback “. This brilliant phrase, heard at Renault in the 1980s, was a reminder that from the 1960s to the 1980s, the stylist, under the yoke of the product department, was content to dress up structures without being able to modify them. From the 1990s to the present day, designers have moved brilliantly from the era of style to the era of design. Now, thirty years later, a large number of them are forced to regress from the era of innovative concepts to the era of simple make-up to dress up the hunchback. ” Touch my hump My Lord, it will bring you good luck! ” I’m not so sure…

If you liked this topic, you’ll like this one too: http://lignesauto.fr/?p=31686