While cars can now be driven without hands, without a steering wheel, and even without a driver, they still haven’t found any technology to sweep their windscreens other than old-fashioned rubber squeegees. And what can we say about its windows? No one is interested in them, except when it comes to repairing an impact! There was a time, not so long ago, when even car designers talked about it, complaining about its weight and cost. The stylists of the time were obliged to fit a beltline “because sheet metal is cheaper and lighter than glass”. This was the case for the design of the Renault 20/30 duo (below) in the mid-1970s.

Today, glazing is much more than just shaped glass. It embraces a host of innovations and plays an integral part in automotive design. Do you even know how it’s made? And more importantly: how are concept cars designed, with all their surprising innovations?

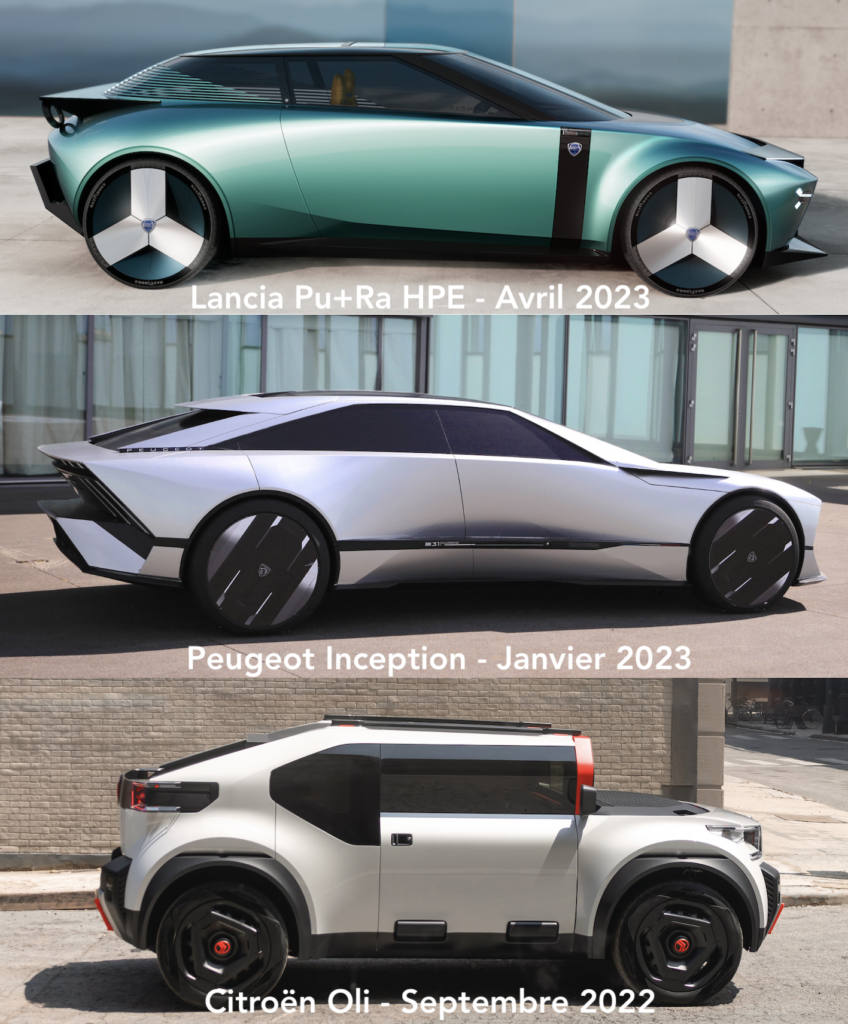

It’s time to clean the windscreen and discover what secrets it holds. To do this, we met Pierre Jego (contact@classicglass.fr), the French representative of DK Prototyping for Automotive Glass. This Dutch company is responsible for designing and producing the windscreens for the Audi Grandsphere, BMW Neue Klasse, Peugeot Inception, Citroën Oli and Lancia Pu+Ra HPE concept cars.

What we know about automotive glazing is by looking at the signature engraved in the glass, such as Sekurit…

Pierre Jego: “Yes, knowing that the ‘Sekurit’ logo, with a K, corresponds to the ‘automotive’ branch of the French glass manufacturer Saint-Gobain*, but that the word has come into common usage with a C to designate toughened glass (‘Securit’).” * https://www.saint-gobain-sekurit.com/fr

You’re going to tell us about changes to the windscreen, but reassure us, they’ll still be made of glass!

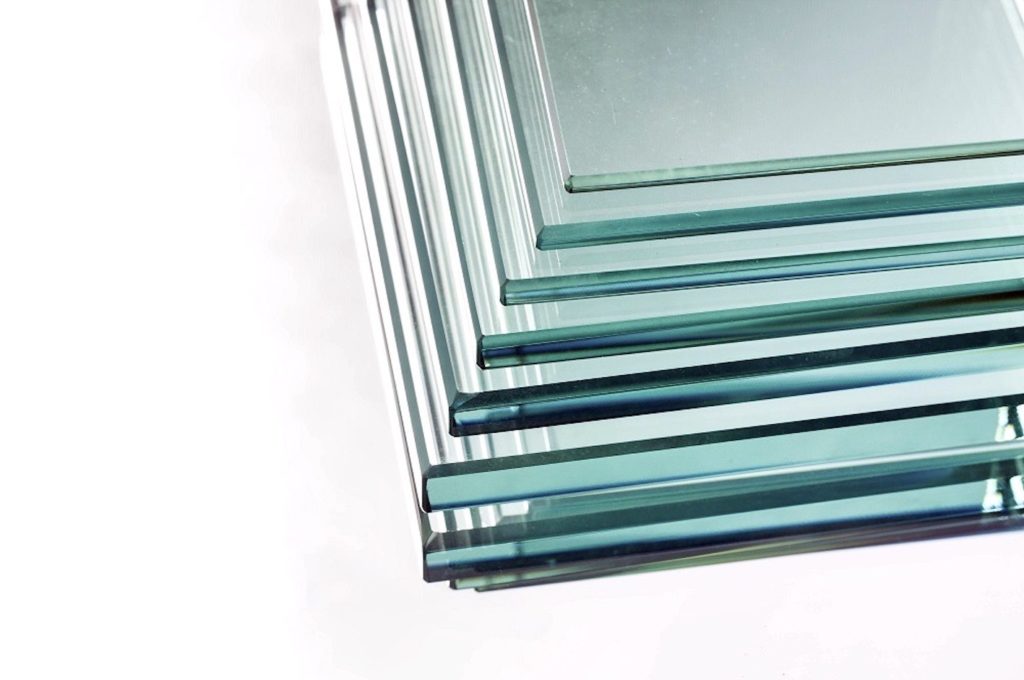

“Yes, but in this case we’re not talking about moulded glass, which is molten glass blown into a mould, like a bottle for example. In the automotive industry, windscreens are made from flat glass. Flat glass is mainly used in three areas: buildings, screens (smartphones, computers, etc.) and cars.”

But a windscreen is anything but flat!

“We use flat glass for its optical qualities, which are essential in cars. The windscreen is then cut into its developed shape, in two dimensions. The next operation is to abrade the edges, for a side window for example. You can touch the edge of the glass without risk of injury, but this rounded, polished joint also serves a useful purpose: it preserves the mechanical qualities of the glass.”

This two-dimensional cut sheet of glass is the only operation prior to three-dimensional forming?

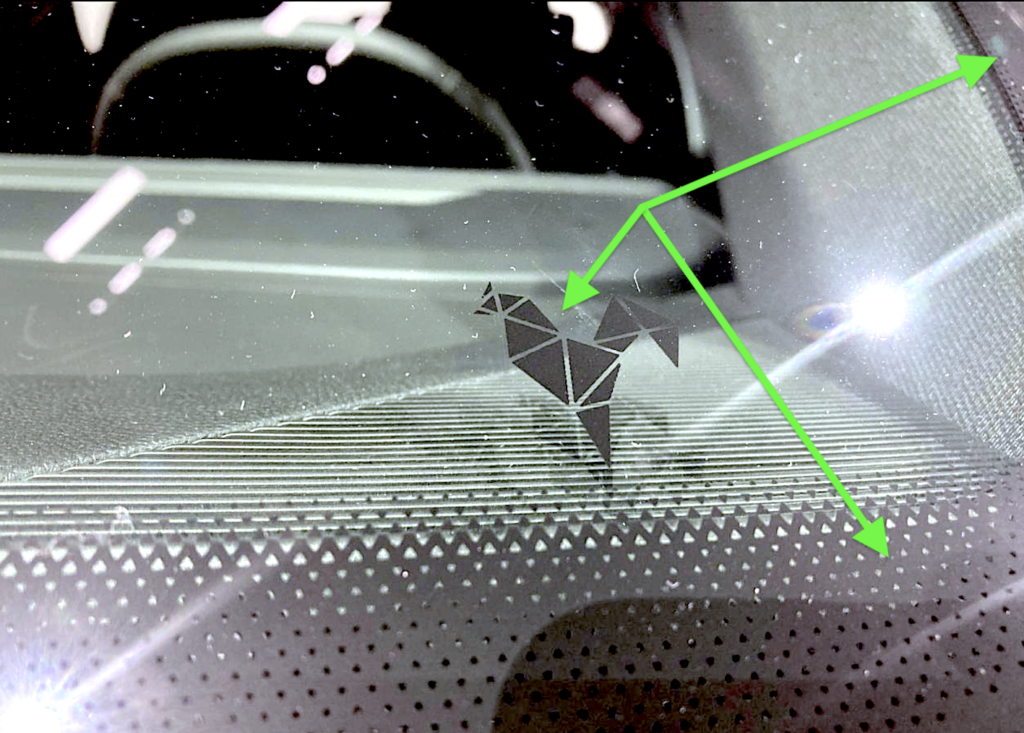

“For the glazing that will be bonded, we also screen-print the edges in black.”

Can you tell us what this screen-printing consists of?

“It’s a black enamelling around the inside of the windscreen to hide the glue joint. Today, windscreens are glued rather than fitted with joints. This black strip, which you can see from the outside, also protects the glue joint from UV rays. It’s actually a black paint around the inside that we’re going to enamel. In other words, it will be baked on to make it very resistant. This operation is carried out while the glass is still flat.”

The screen-printing contributes to the design of the car with its gradients in the form of small dots.

“You can see the aesthetic side, but this gradient has a very specific function. There’s a phenomenon when you heat glass: it reacts differently when you get to the black band that absorbs the heat. There is therefore a slight risk of optical distortion. The gradient of screen printing then smoothes out the temperature differences and eliminates this potential distortion.

So this silkscreen has to be black?

“No, it can be done in any colour. At the time, in the years 2000-2010, we tried to sell this idea for special series. But costs put this aesthetic possibility out of reach. It’s not more expensive to make, but the extra cost comes from managing windscreen references. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case, and I really regret that. The Citroën C3 Aircross model below had a rear quarter window highlighted with an orange silk-screen line. You could do the same thing on a windscreen…”

Now that the 2D windscreen has been screen-printed, how does it become curved and conform to the dimensions imposed by the manufacturer?

“This is called forming, and it’s the most technical and strategic part of automotive glass. So far, any glass industry can do everything we’ve just seen. Forming, with the excellent optical quality demanded by the automotive industry, is more complex.”

And there’s only one way of doing this?

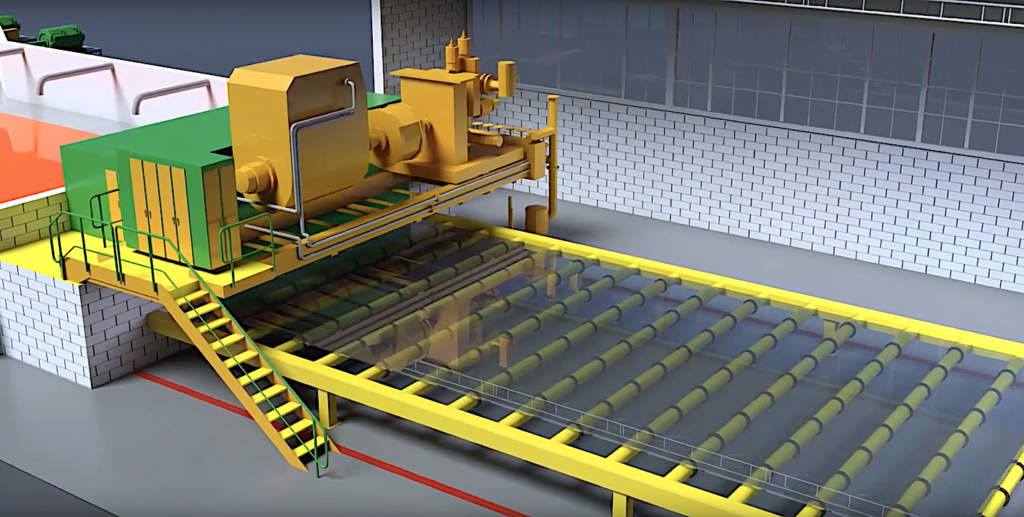

“No, there are two methods: gravity and pressing. Most of today’s windscreens are made by gravity. We take the 2D glazing and place it on a metal tool that only takes the outer 3D edge of the required part, by about 2 cm. The inside of this tooling is empty. All it has is a strip of metal in the shape of the windscreen frame (we call this tooling the ‘skeleton’), a shape produced by the manufacturer’s 3D digitisation.”

“We place the cold glass in 2D on this skeleton and introduce it into the furnace, which holds at least thirty pieces at a time. The furnace gradually heats up to 650°C, and the heated glass collapses under its own weight, maintaining the desired shape at the edges. At the end of the process, when it comes out of the oven, the windscreen has taken its shape, held together only by the edges of the skeleton.”

So there’s no mould?

“No, it’s the weight of the heated glass that, by gravity alone, forms the windscreen, which is held in place all the way round on the skeleton. The tolerance on the skeleton is minimal, in the region of plus or minus 1 to 2 millimetres, so that it can be fitted to the body painted on the manufacturer’s assembly line. On the other hand, for the inside of the windscreen, the tolerance is greater because it is the outside shape of the curvature. The only constraints, apart from transparency, are surface regularity for the optics and for wiping. These tolerances are achieved by controlling parameters such as heating time, cycle time, etc.”.

Is this the process used to create the bubbles in the hatchback windows, as on the Renault 25 and Fuego from the 1980s?

“All cars today have double curved windows. In other words, they have more than one radius. To the main radius, which is often longitudinal, we add a transverse radius, for example for the tailgate bubble. The limit is reached according to the differential between the two radii: the smaller the main radius (longitudinal, for example), the larger the second radius. This is the case with windscreens, which generally have a small main radius (from the top to the bottom of the windscreen) and a larger one (laterally) to adapt to the pillars. The more curvature there is in one direction, the less there can be in the other. And that’s why our company DK is involved in the early design phases of a concept car, for example, to determine very early on in the process whether a shape is feasible in glass or not”.

Are designers well-informed about this type of production, whether it’s one-offs for a concept car or mass production?

“To a certain extent, designers are aware of the limits of glass forming. But when I go to Vélizy (Stellantis DNA) or Guyancourt (the Renault Technocentre), it’s often long before the model has been entrusted to a prototypist for production. For example, for the Lancia Pu+Ra HPE concept car in Italy, I went there long before, when the model was still in polystyrene at scale 1.”

“The designers had applied black ribbons to delimit the glazing surfaces and asked me if this was feasible for the rolling concept car. Depending on their drawing and cut-out, I may or may not make changes. It’s also worth noting that the Lancia Pu-Ra also incorporates opaque areas on the windscreen (to replace the sun visor) and a mobile ‘Smart Glass’ type dashboard for projection (see end of post)”.

DK specialises in small series. How long have you been the company’s representative in France?

“I’ve been working for DK (https://www.dk.nl/?lang=fr ) since 2021. It’s a small Dutch company of around twenty people, founded by Bart Driehuis, which started out by remanufacturing glazing for classic cars. Today, around a quarter of the company’s turnover comes from modern concept cars, with the rest from prototyping and very small production runs for all kinds of uses and automotive customers.”

At the time, DK mainly worked for german manufacturers?

“In the 1990s, Bart Driehuis was approached by Volkswagen to make special windscreens. Satisfied with the result, the group entrusted him with all glazing orders for Volkswagen concept cars. Since 2000, DK has had the majority of the glass prototyping business for German concept cars.”

But the glass giants know what they’re doing, don’t they?

“The glazing industry is volume-oriented. Bart Driehuis, the boss of DK, has developed a manufacturing process that is not the one we have been talking about, but which is unprecedented. DK is equipped to manufacture glazing by the unit or in very small series. The glazing is very attractive, with perfect optical quality, which is essential for concept cars. A group like Saint-Gobain can indeed do this, but their speciality is production runs of at least several thousand units.”

And today you also work for the two French groups?

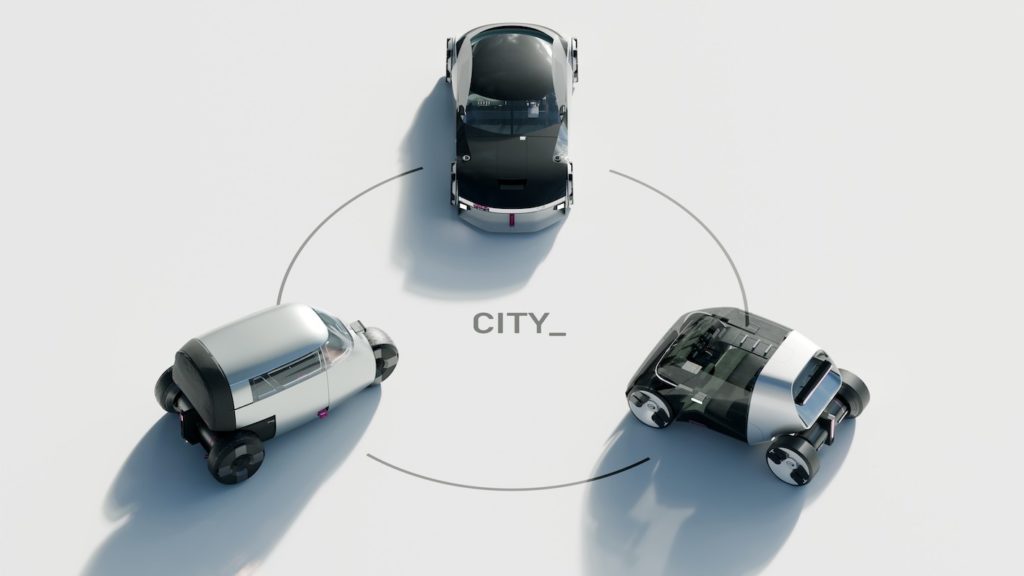

“Yes, and only recently. We got in touch with the people in charge of producing the Stellantis concept cars, and we were able to deliver the curved side windows for the Oli concept very quickly, as they seemed to pose a problem in terms of production and lead times. Since then, we have been systematically involved, and have developed and supplied the following concepts. We’ve been doing the same with Renault since this year, but I can’t give you any names because the concepts have not yet been unveiled. Finally, we are working for a number of automotive start-ups, whether on a 12-cylinder hypercar or a small ‘new urban mobility’ vehicle.”

DK specialises in small series, but for a concept car you only make one part?

“No, it’s usually three parts. For the Lancia Pu+Ra HPE, that’s what we produced because the life of a concept car, especially on the road, is full of hazards. There can be breakages at the time of assembly, but also during its life. And redoing a windscreen means that the oven has to be restarted at a higher cost.”

On the Stellantis side, apart from Oli and Pu+Ra HPE, you worked on the glazing for the Peugeot Inception concept car above…

“On this project, we were involved at a very early stage. For the prototype’s grille, the design team wanted a mirror effect. Matthias Hossann’s team – Peugeot’s design director – asked us if it was possible to make the whole thing in glass. We came up with a semi-mirrored glass that remains transparent, and we presented it in two thicknesses to achieve an astonishing final result.”

“The idea of dichroic glass for the windscreen came from Maud Rondot, from Peugeot’s colours and materials team (Maud has now been promoted to head of the C&M department at Peugeot, editor’s note). We showed them the flat glass available from a german glassmaker (Shott) who makes special glass. Peugeot chose Narima glass.”

Is this glass suitable for mass production?

“Yes, technically it can be industrialised. But there would be a problem of longevity, with a type of automotive aggression that is very different from the world of architecture where it can be used. And I’m not sure it would pass all the approvals. In addition, this glass has no thermal properties. Dichroic glass is primarily used for design purposes, since it offers different colours depending on the angle from which it is viewed, but it has no infrared treatment to protect it from heat.”

One final question: is polycarbonate still more practical and cheaper for a concept car?

“The glassmakers are talking about plastic windscreens! There are two possible types: Plexiglas, which is banned for use in cars because it breaks and becomes sharp. Then there’s polycarbonate, which is used in particular for motorbike visors. It’s a solid resin that looks good but sometimes ages badly… Glass is still the material preferred by designers: it’s better quality, more resistant, it ages better and, above all, it looks perfect under the neon lights at trade shows.”

BONUS

To be (even!) more intelligent after reading…

Pierre Jego sheds light on innovations in glazing.

“For a long time, glazing has incorporated many functions, some more visible than others: thermal, such as the anti-infrared coating to reduce heat in the passenger compartment, acoustic (special interlayer inserted between the two panes of laminated glass), heating network and integrated aerials, etc. Some innovations have not really found their market: hydrophobic coating, anti-reflective coating, anti-laceration, etc. Some innovations have not really found their market, such as the anti-reflective coating. Some innovations have not really found their market, such as hydrophobic, anti-reflective and anti-laceration coatings. Similarly, the trend towards slimmer glazing, motivated by significant weight savings (2.5 kg per m2 and per mm of glass), has slowed down somewhat in recent years, partly because of the deterioration in acoustic performance.”

Smart glass is an opaque pane that can be darkened on demand, possibly in controllable segments, as on the roof of the Renault Rafale (below), scheduled for 2024.

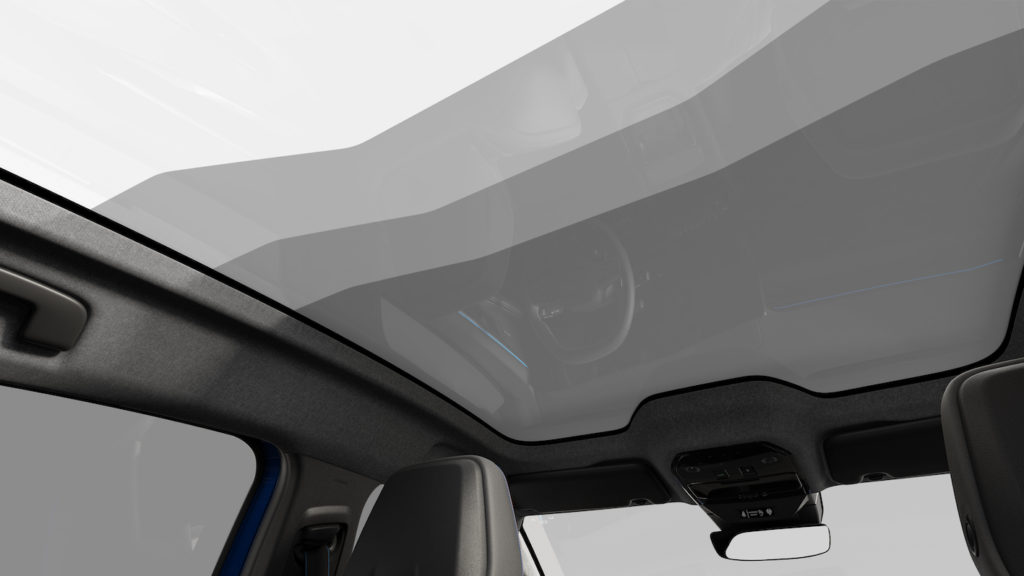

HUD (head-up display) is the projection of information by reflection on glass. It’s not new, but the technology has come a long way, and coupled with AI, we’re starting to see some quite surprising uses. BMW’s Neue Klasse, which we worked on and which will be unveiled in Munich in September 2023, features a HUD covering the entire lower black band of the windscreen. Generally speaking, the issue of projecting images onto windows is of great interest to designers.

NB: the HUD on the new Citroën ë-C3 below does not adopt this principle, since the projection is not on the glass and the base of the windscreen, but on a dedicated element of the dashboard.

Laminated side windows. Laminated glass consists of two sheets of glass sandwiched between a plastic interlayer, usually 5 mm. It offers better sound absorption than toughened glass (a single sheet of glass, usually 3.5mm). As a result, more and more side windows are being converted to laminated glass, particularly on electric saloon cars.

Panoramic roofs, flush glazing and integrated information are a major trend, and many designers are imagining real glass “bubbles”, incorporating thermal functions. We are also seeing the emergence of glazing with image projection or solar control. This requires perfect fitting and alignment, and therefore high quality glazing: curvature tolerances, surface regularity, optical reflection.

Photovoltaic glass can incorporate photovoltaic cells into laminated glazing. The yield is not very high, but the Wahoo effect is undeniable… The very recent Fisker Ocean below features a large solar-powered sunroof. Other projects are under way. We also know that transparent or semi-transparent PV films are being developed.

The limits of glass forming. The glazing contributes to the car’s style, and as such, the question of the feasibility of the volumes arises at a very early stage. The main constraint is the complexity of the shape. All current glazing is double-glazed, meaning that it has several radii of curvature, both longitudinally and vertically. The more you bend in one direction, the more difficult it is to bend in the other: the spherical areas are the most complex to create.