Benoît Jacob designed the Renault Fiftie concept car, the Renault Spider, the Renault Laguna 2 and the first Dacia Logan. Initially based in Munich, he worked at BMW on the birth of the i3 and i8, before moving on to work with Chinese automotive start-ups based in the German city. Today, he ‘designs’ teams and manages them! The man is not looking for light. So we lit a little candle in search of this designer and found him travelling between Corsica, China and the French capital. Born in Belfort in 1970, Benoît Jacob has built an atypical career for himself, and his views on the world of design are instructive, as you are about to discover.

Bio Express : a great business card!

-Born in Belfort in 1970

-Renault Design Industriel in 1991

-Art Center College of Design in 1992

-Renault Design Industriel in 1994

-Volkswagen in 2001

-Audi in 2002

-BMW in 2004

-BMW i in 2009

-Byton in 2016

–NIO in 2022

-GAC since september 2024

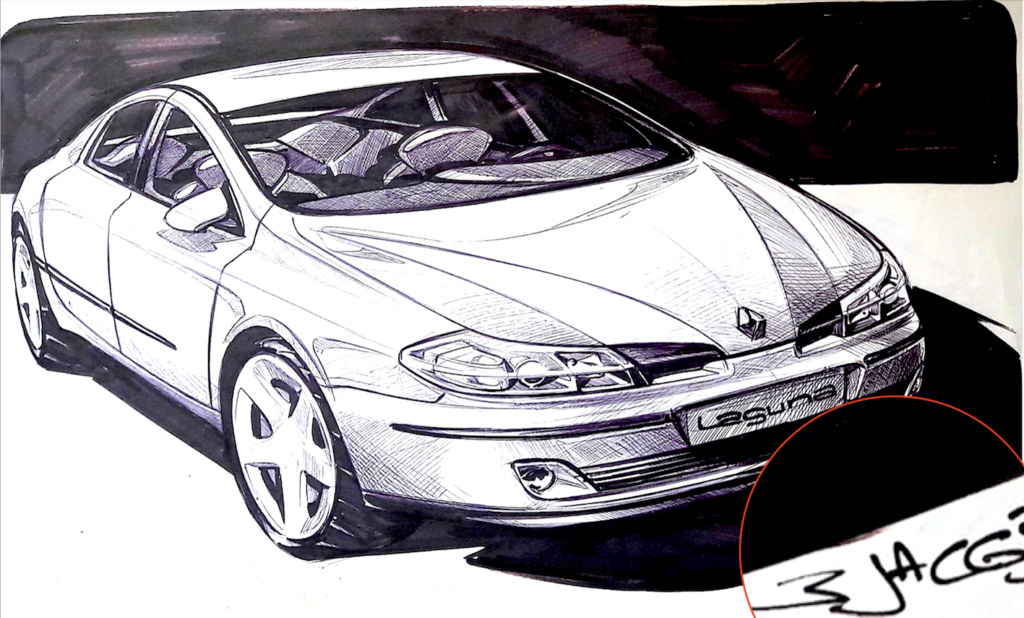

We’re after you because we still think of you as the designer of the Renault Fiftie concept car in 1995, the Renault Sport Spider in the same year and the Logan in 2004. Then you were responsible for the design of the BMW i3 and i8…

Benoît Jacob cuts me off: ‘ That’s a long time ago!

Of course, so let’s start at the end, which is today. You have just joined the Chinese group GAC*. Can you tell us why?

I’ve been self-employed for the last two years and I’ve had quite a few contacts with companies in China. I approached GAC because I felt that, in terms of design, it was a brand that seemed to me to be the most international…

*GAC stands for Guangzhou Automobile Cie, China’s 6th largest car manufacturer. Head office in Guangzhou.

You’re going to find some nice acquaintances there, particularly French ones!

GAC’s head of global design, Zhang Fan (below at the Mondial 2024 with Benoît), has an international reputation (he used to work for Mercedes, NDA) and he has actually hired some of my friends from the Renault period: Pontus Fontaeus at the Los Angeles design centre, and Stéphane Janin at the Milan studio. I said to myself that this group took design seriously, and not just in words, but in deeds. They have set up a global design organisation of around 400 people.

Will you be in China, Milan or Los Angeles? And in what position?

I’ll be in China. During the year, I spoke with Zhang Fan and the feeling immediately took hold. He’s a very busy man and I’m going to be working alongside him as Executive Design Director. I’ve already started (on 18 September last NDA) after discovering the design studios in Guangzhou last August.

You’re continuing your expatriate life! After Munich in Germany, China. It’s quite special…

China is no stranger to me. I’ve been there regularly for the last fifteen years. But it’s true that even if I’m used to living in Germany with my partner (BMW, Byton and NIO, we’ll come back to that later NDA), moving to China isn’t an insignificant move! I once had the opportunity to work there, but my son (Charles, now a Renault designer) was still studying, and we didn’t want to move too far away. The situation today is different. First of all, I’d say that integrating into the company has gone better than I’d imagined. Today, my wife and I are thinking more along the lines of ‘Do we live in Guangzhou or Hong Kong, for example?’ I can stay in Guangzhou, no problem, but we still have to think about the family and find a place where there are as many opportunities as possible to socialise. We’re used to expatriation, but it’s clear that in Munich there was a large French community. It’s a bit trickier in China.

Let’s talk about Munich. You’ve had three very different careers here at BMW (then BMW i), Byton and Nio…

I was poached by the start-up Byton (a Chinese manufacturer born in 2017 which went bankrupt in 2023 NDA). I had no real reason to leave BMW other than a taste for adventure and renewal: I liked the start-up spirit and we were starting from scratch. We had to invent everything! I started by suggesting that we set up the design studio in Munich, because I had a network that could help us, especially for a start-up…

It was the start of a period when the Chinese were setting up their design centres in Europe and poaching some pretty crack European designers!

Even though Nio had been there before, I think I accelerated things a bit! Munich was a kind of Trojan horse for the Chinese… It was only logical that the Chinese manufacturers should come looking for European expertise.

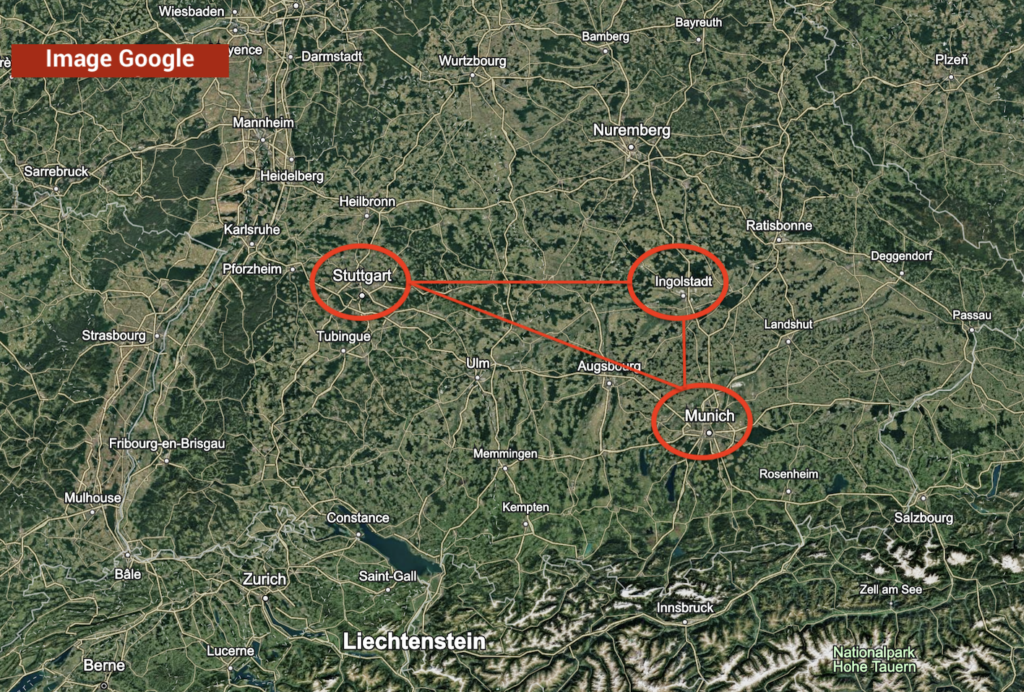

Munich has become a real hub for the Chinese. How do you explain this compared to Turin?

Munich is at the heart of the golden triangle of premium manufacturers (above): Stuttgart, Ingolstadt, Munich with Porsche, Mercedes, BMW and Audi. The network of quality subcontractors is just as well developed as in Turin. For Byton and NIO, I could count on an ecosystem and a network of partners to get the work started straight away. With the necessary skills in all areas: modelling, model making, etc. I designed all Byton’s concept cars within this perimeter. Now, when Chinese manufacturers consider Europe, Munich often comes first.

And the Chinese have been known to pull out the cheque book to seduce European designers!

Frankly, in my case, I had nothing to complain about at BMW! I was at an executive level, on the design steering committee and I reported directly to Adrian van Hooydonk (Head of BMW Group Design NDA). I left BMW with nothing to complain about! The motivation was elsewhere. After all, we designers need intellectual stimulation. At BMW, I was mainly in charge of advanced design, and at the time, the ‘i’ branch was more uncertain in its definition and long-term strategy. BMW has efficient management, but it still took two or three months to validate a decision that today I take in two or three days with the Chinese…

There is a significant proportion of French designers among Chinese manufacturers. Is this just a coincidence, or is it a sign of very good French training?

It all goes back some thirty years, to when Patrick le Quément (above, in front of the VelSatis concept from 1998) took over as head of Renault styling, transforming it into Industrial Design and internationalising it. Jean-Pierre Ploué followed the same logic a little later at PSA. This led to a lot of contacts with design schools, and the whole process inevitably raised standards. I think French designers have a mix of skills and a lot of talent. French culture has a habit of questioning everything, which sometimes creates a whole host of problems! But in design, this culture pushes us to think in terms of always wanting something new, something never seen before.

When you knocked on Renault’s design door in 1991, you couldn’t have come at a better time!

I was brought up at Renault by Michel Jardin and Jean-François Venet, who said, ‘No, it’s not new enough, we want to see something new’, which is exactly what the Chinese manufacturers were lacking. Mind you, we’re not going to teach them how to make cars! Today, they know how to do that very well. On the other hand, culturally, China started by copying, because for them, copying means celebrating a good idea! Over there, we find a more pragmatic culture, in a context where the majority of Chinese manufacturers are very young and have no history.

In fact, starting from scratch is much easier than for European manufacturers, some of whom are more than a hundred years old and have to transform their sometimes burdensome past!

Yes, even if there are advantages to having a history: you can create a brand image with more scope, and that’s an opportunity. But it’s true that it can be a burden in some cases. I find that some European manufacturers are sometimes too locked into their dogma, but fortunately there are some who are doing quite well.

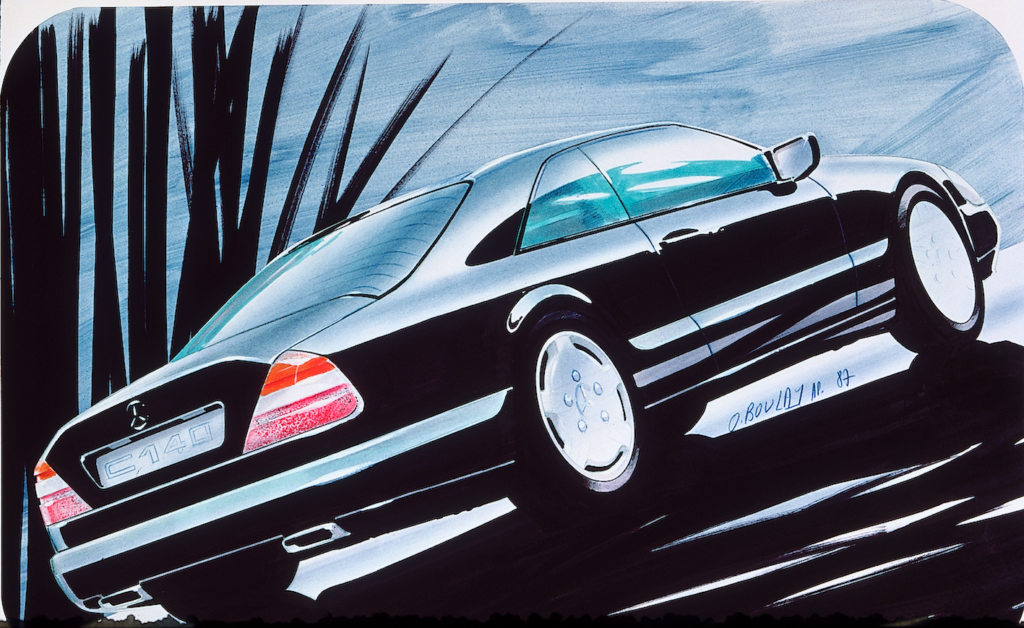

All this reminds me of Mercedes, which relied on a masterful design in the 70s and 90s, with Bruno Sacco, who recently passed away. A history that wasn’t heavy, but on the contrary a solid base with a perennial design…

Absolutely! I’d say ‘ Bruno ! coming back ’, because I’m a big fan of Mercedes from the 1980s. I’m an avid collector and I wouldn’t give up a 500 SEC coupé from the 1980s (above), or even a 190, which for me remains a design masterclass, with a balance between functionality, novelty and modernity that I don’t find in what they’re doing today. Generally speaking, and in the image of our society, design sometimes seems a little less sophisticated, a little more hackneyed. But as I always say, car design reflects society’s aspirations.

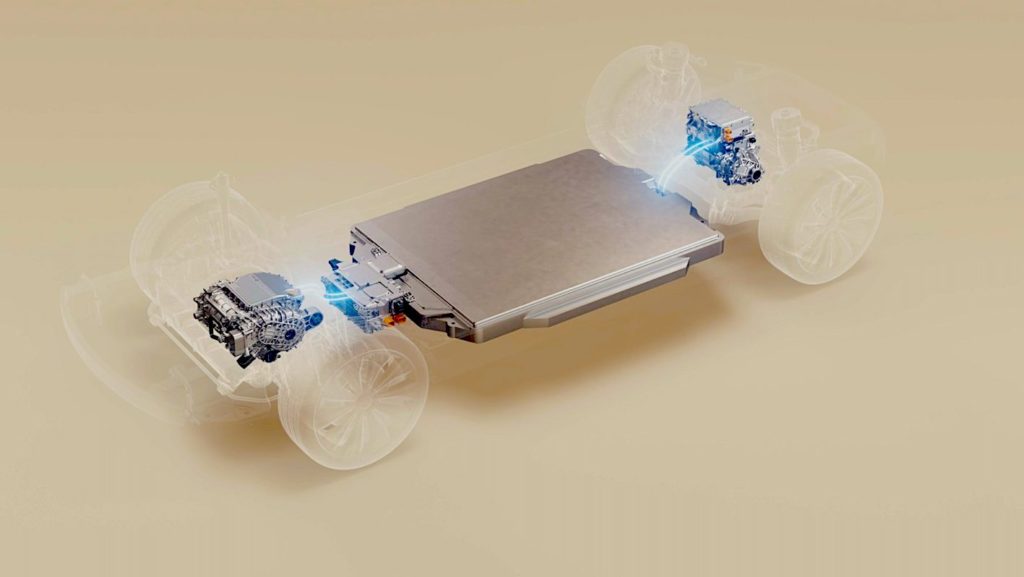

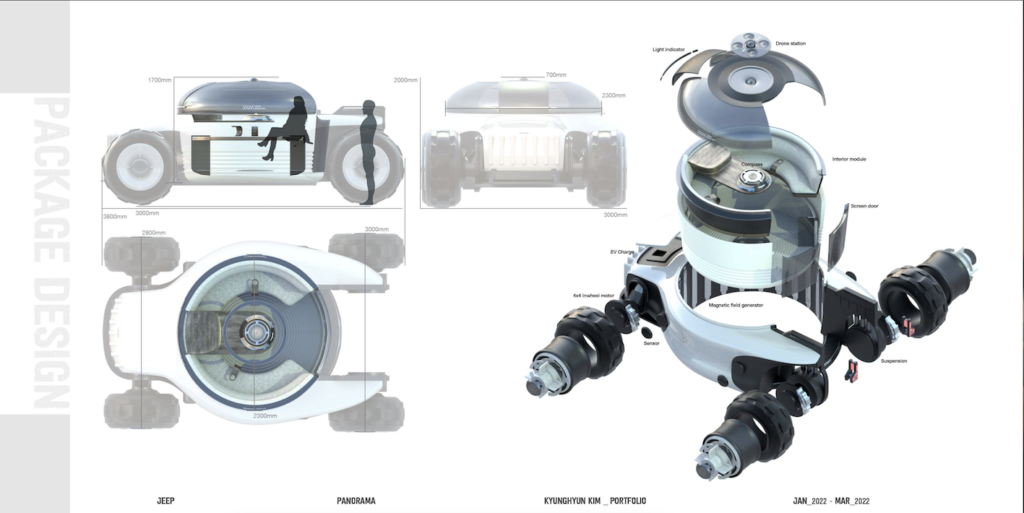

Society, in Europe in our case, is forcing us to go 100% EV. You designers don’t seem to be taking advantage of the new platforms (like the one above from NIO) which should have given us a revolution in terms of design?

First of all, we have to start from the premise that, after more than a century, the car is still a product which, in its basic definition, has reached a very optimised technological and functional maturity. If I compare it to the space or aeronautics industries, I would even say that the car is more complex in the sense that it is produced in millions of units, put into the hands of the greatest number of people, without any advanced training, and that it meets unavoidable cost, safety and legislative objectives. As a result, the corridor of possibilities shrinks over the decades. Expectations or observations in terms of safety, aerodynamics, emissions or even factory costs, with a network of structured suppliers, have in a way defined the contours of a car’s silhouette.

Patrick le Quément said when he joined Renault that ‘style dresses the hunchback’. We’ve come back to this when we see the carry-over practised at Stellantis for example: platform, windscreen bay, windscreen, rear hard points, etc…

Let’s just say that these days there’s a tendency to focus more on style than on design. Design is a global thing. It’s not always easy to use this word, because in English, a designer is also a conceptor, or even an engineer. So it’s not necessarily the person who holds the pencil with emotion. Design goes beyond the traditional designer’s activity: integration, proportions, balance, all that is design, it’s the right technology, the right objectives in terms of integration…

Do you think Stellantis goes too far in the carry-over of its multiple brands?

Stellantis is an excellent example of style and there’s nothing wrong with that. I’m a stylist myself, but I’m also a designer. Things are done in a different order. In the context of a huge, multi-brand group, with as few platforms and components as possible, the corridor is very narrow. But we can still do a lot of things on very rigid bases. Let me give you an example from BMW: in the advanced design department, we always positioned previous generations with the future generation we were working on. From one generation to the next, the gap between the hard points of each of them became thinner and thinner, but the silhouettes were still quite different.

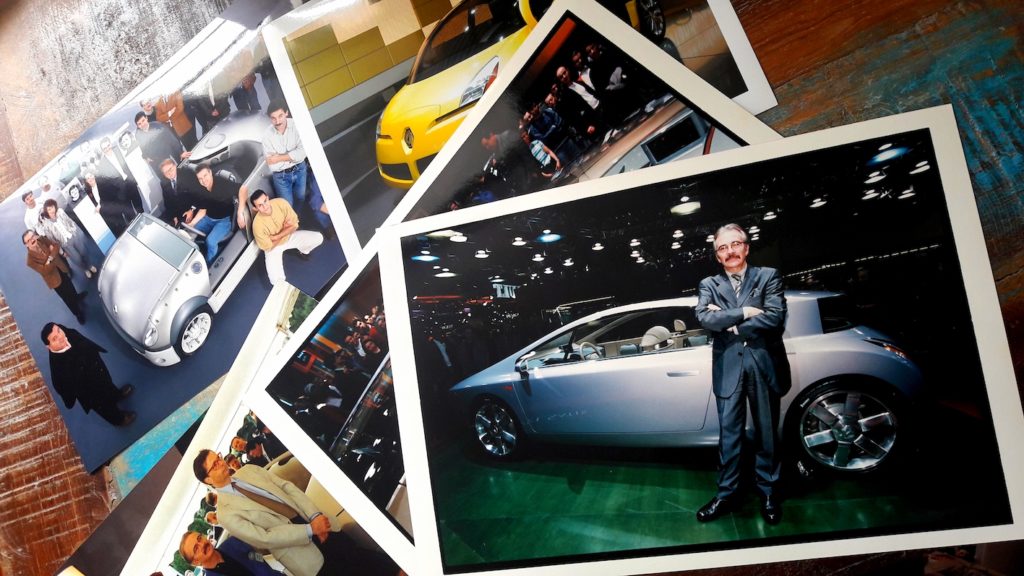

You mentioned BMW. Can you tell us about the fabulous adventure of the BMW i3, a veritable manifesto for the brand, and one that’s even produced in series?

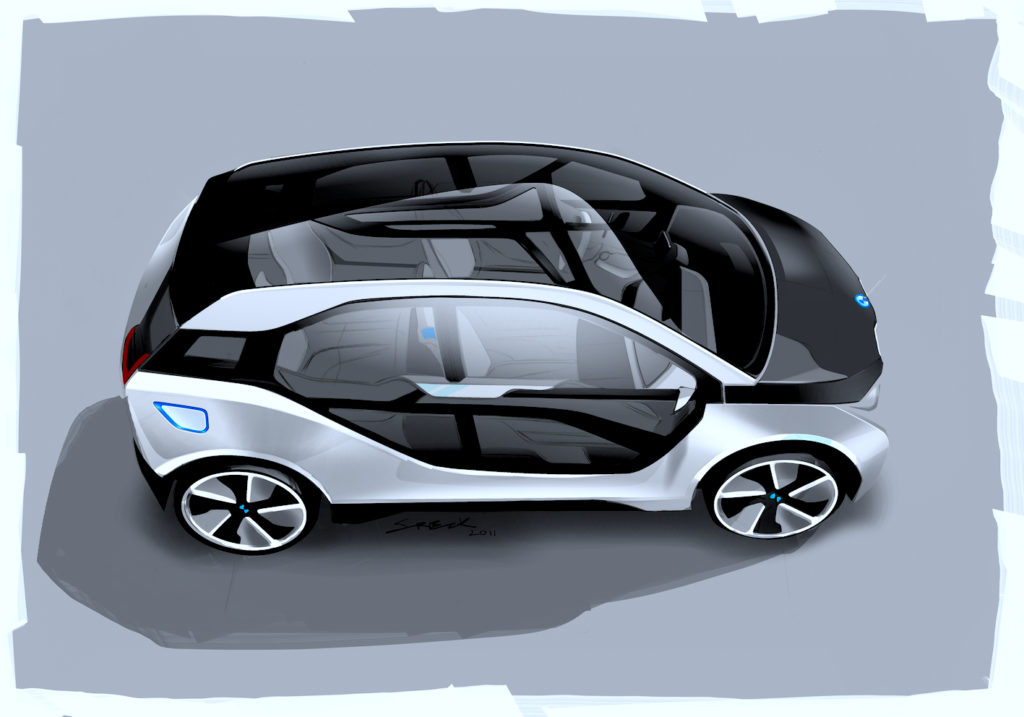

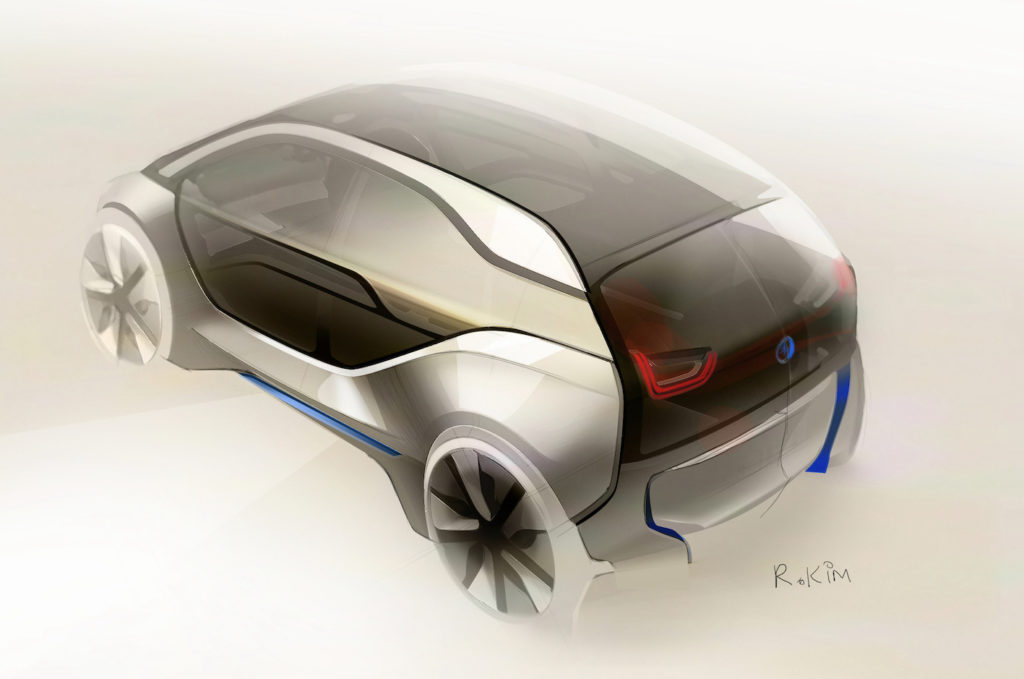

The origins of this programme lie in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008. At BMW, under the leadership of Norbert Reithofer, they asked themselves how they could ensure the group’s survival in a legislative context that was likely to be different, particularly in terms of emissions. The i3 and i8, especially the i3, had to demonstrate the company’s determination. BMW has always had a fairly acute sense of strategy and anticipation. There were many meetings, and the management showed a desire to transform BMW. One of the conclusions was to demonstrate our commitment to more sustainable mobility. And ‘ let’s be among the first! This materialised with the BMW i project, and given BMW’s culture, engineering laid the innovative foundations of the programme: lightweight car (steel is heavy, can we envisage other technologies and in the premium could we afford carbon)….

…But how do you dress it up? We chose thermoplastic, a lighter material that we even imagined could be dyed in the mass. This idea was later abandoned.There was a lot of motivation in terms of the energy needed to make a car. The programme was based on the principle that stamping, cataphoresis and painting consumed too much energy… there was a global vision that allowed savings to be made not only in the use of the vehicle, but also during production. It went a long way. So that was the brief I received when I started the prospective design phase. We had to think about the car differently.

We’re still amazed that the management was able to take such a bold and commendable step.

Let’s just say that the BMW i3 served as a manifesto, a bit like the Z1 in its day. This kind of laboratory vehicle made it possible to get a clear message across both internally and externally. They were two polarising vehicles and they divided the board, so that was reflected in the strategy.Some people were hesitating: should we continue with these two ranges (BMW i and BMW) or should we adopt a safer strategy with multi-energy platforms? There were a lot of questions. The brand initially evolved through an ‘i’ label and dedicated technology, but now the strategy is based on multi-energy platforms, which is probably a good strategy.

The i3 is a real UFO for BMW. How did you approach its design?

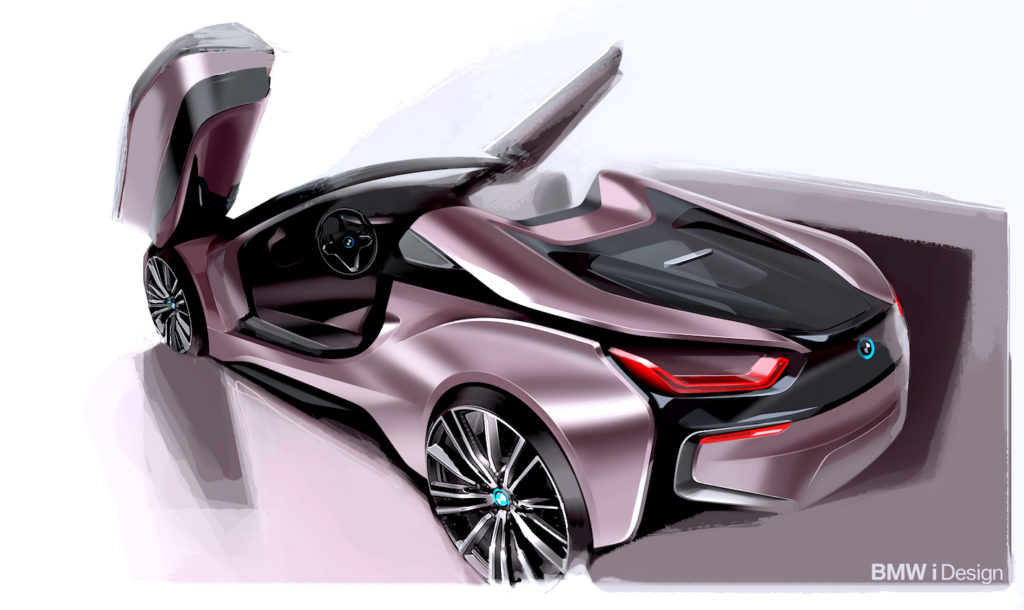

The i3 has a strong contrast between its parts, it’s very graphic but that’s not an artistic motivation, it’s purely functional. The coefficient of expansion of the material used for the bodywork was different to that of steel. Personally, I’ve often compared this car to the planet: there’s a heart – the core – and tectonic plates that move around it.Traditional steel bodywork is stable: you wedge the doors open and everything’s fine. Here, we had to take expansion into account, and this was even more of a problem with the i8 (below), because unlike the i3, its bodywork was truly multi-material, with aluminium doors and thermoplastic rear wings, all with different coefficients of expansion. It was great fun!

Before you left BMW, did you have any replacements planned for the i3 and i8?

There was never any question of a replacement programme. In fact, the only thing that was certain when I took charge of the programme was to design the i3, while the i8 came later.Marketing and the product planners were wondering whether a city car was in keeping with BMW’s image. The i8 helped to consolidate the brand image, at the same time as the BMW i approach.

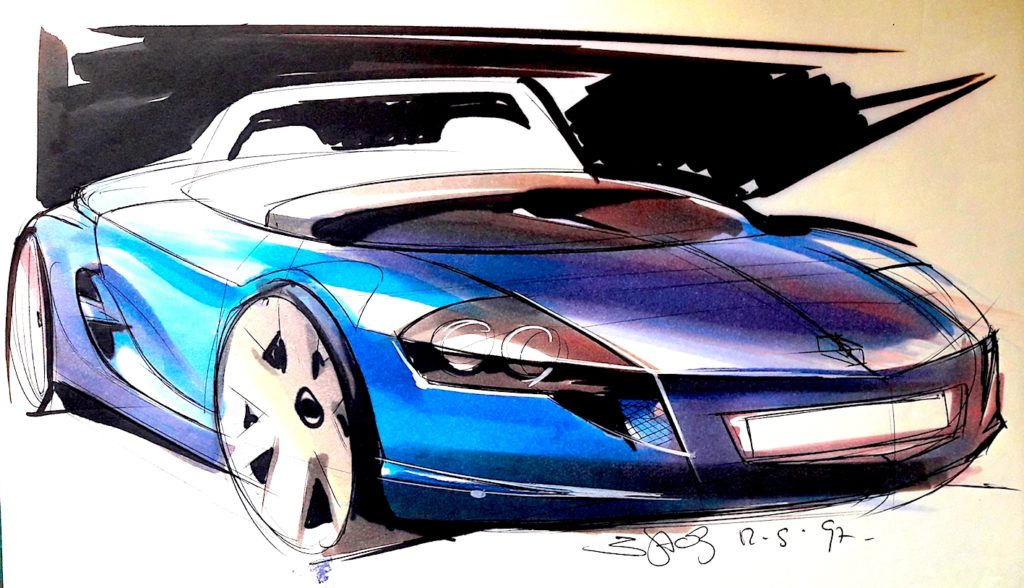

Your career has focused on this type of programme, notably with the Renault Spider above and the Dacia Logan.

I’ve traditionally chosen companies on the basis of their courage in terms of design. At BMW, they have the courage to do something different. At Renault, I experienced a golden age, which wasn’t always reflected in series production, but I have excellent memories of it. On the other hand, I encountered less of this type of approach at Volkswagen during my time in Sitges.

The Logan (above) is still a nice addition to your business card!

Let’s just say that I don’t have a favourite range of cars… I was talking about intellectual stimulation, and I’ve always had a particular appetite for things that are different, new and off the beaten track. The Logan was not Miss World, that’s obvious, but there was an intelligence behind it, and I like intelligent products that make sense, I have fun with that.

You also executed the exterior styling of the Fiftie concept car in 1995 above. Given the success of retro-design, it’s easy to think that Renault missed the boat. Any regrets?

No, no regrets, no frustration. This concept car looked good. Whether it would have found its market in the mid-90s, I don’t know…

What are your feelings following the industrialisation of the R4 and R5 E-TECH… Is relying on the past a way of reassuring ourselves?

There are several explanations. Personally, I grew up at the end of the thirty glorious years, and we thought that tomorrow was going to be incredible!There was the conquest of space, with the American shuttle in 1981, the year of the TGV in France. We were attracted by this future, which had been reflected long before in car design, particularly in Italy in the 1970s, and even before that in the United States. We had this appetite for tomorrow, including in other worlds, such as fashion with Cardin or Courrèges. We used to think that ‘tomorrow is cool ’. Today, we’re no longer really sure that tomorrow will be cool, and that translates into fear and a desire for reassurance. I was also talking about the maturity of technology, which means that we’re doing more style than design. It’s all about storytelling: what story does the car tell? There may be some interesting avenues to explore, because in the narrow corridor I was talking about, there are still an enormous number of stories to tell, and that’s the art of the designer. The retro side, why not. I don’t know how I’d approach it, but I wouldn’t make it a dogma.

When you were designing the Fiftie – 1995 – GAC had not yet been born – 1997 – It seems quite unthinkable!

The Chinese car industry is new. It was developed under strong political impetus, but above all, with a long-term plan. Don’t forget that Chinese culture is based on the long term…

It’s a long process that could be undermined by Artificial Intelligence. What do you think of its arrival in design studios?

I’m looking to the future, but I’m from the old school.AI aggregates data, and the term ‘data’ refers to the past, not the future. That’s not to say that it doesn’t give birth to interesting subjects, but it’s still iterations on things we know. In the first instance, maybe that’s enough… During a recent speech at a school in China, at the time of Marcello Gandini’s death, I asked the question: ‘Can AI be the next Gandini?‘ Marcello Gandini or other great creators, like Elon Musk or Steve Jobs, are or were guys who refused reality to do things the way they did them. They had – or have – a way of distorting reality to make something new. AI is not yet capable of that.

So AI can’t be a genius?

Let me take the example of Elon Musk. His Starship rocket, 120 m high with its booster returning from space to the launch pad, was simply unimaginable before.To achieve this, in addition to the baggage of genius and madness you have to deploy, you have to refuse to accept reality. So it’s a question of courage. That’s what innovation is all about. Is AI capable of questioning reality? That’s the question I’m asking myself and I don’t have an answer to that…

Today’s generation thinks it can be done. And as far as budding designers are concerned, software like Blender offers creative possibilities for almost everyone…

Yes, it has to be said that there are more and more graduates coming out of schools and it’s not easy for them. At the same time, Blender is accessible to everyone and many young creative people (see above) know how to use it. For this reason alone, not to mention AI, the profession is going to change dramatically over the next five years.

To start or accelerate a career as a designer, as in all professions, you need to be able to count on good contacts. That’s the most important thing, isn’t it?

Yes. I always say that for a career, there’s talent and hard work, but there’s also the luck factor. At Patrick le Quément I was lucky enough to meet the right people. I didn’t have a design diploma yet, no A-levels, nothing. It wasn’t easy. So, yes, guys like Michel Jardin (above) and Jean-François Venet, whom I adored, are still with us: I really admired them. I loved working for them, as I did with Griffa for modelling. They all taught me a lot and I still repeat what they taught me in the studios today.

Today, at the age of 54, the Renault era and even the BMW era seem a long way off, while you’re living a great new adventure…

…It’s quite a gift you’ve been given! You’re lucky that life offers you this kind of situation and the chance to discover something new.You just have to make it happen!

You’re a decade behind Jean-Pierre Ploué who, at 62, will be handing over the keys to Stellantis Europe’s design over the next few years. Would you be a candidate for a return to Europe in such a position?

It’s not for me to ask myself that kind of question. Jean-Pierre has done an incredible job. I’m certainly a big fan of BMW, but I’m also a big fan of what Ploué and Gilles Vidal did at the time at PSA, in terms of design quality – creativity and execution – in the mainstream, with packages that weren’t always easy. Respect. If I were in the shoes of Stellantis management, I’d take someone who could keep up with two generations of product renewal. Maybe I’m a bit old for them! But it’s true that with BMW, with the assembly of Byton and NIO, I learnt a lot, in particular how to put together good teams and manage them. I know what a design organisation is, I know all the technical aspects, but also the political aspects inherent in this job.

After your two ‘Chinese’ periods in Munich – Bydon and NIO – did you try to make contact with a European manufacturer?

When I left NIO, I offered my services in Europe to Jean-Pierre Ploué, Laurens van den Acker and Adrian van Hooydonk, but to no avail. My wife told me that ‘now that you’ve gone to the Chinese, the Europeans don’t want you any more!‘ If I were a European manufacturer, afraid of the Chinese, I’d say to myself that it would probably be a good idea to have someone who knew what it was like on the other side of the fence.And on the other side, it’s not at all like in Europe. For example, I’ve had much more impact in ten days at GAC than in a year at BMW, in terms of decisions and the path to take! And when I say a major impact, I don’t mean redoing a small section of the shield, I mean making fundamental choices!

The last time we spoke, you were restoring one of your classic cars. Do you still have them?

Yes, they’re in Munich. I bought them about ten years ago and restored most of them with my own hands. I’ve restored my old Ferraris, in particular a 308 GTS, a 308 GT4 and a 365 GT4. I also have a BMW 850 V12 5-litre, with the1st generation M60 engine, which I’ve driven a lot. But I had to put the brakes on, because if I’d let myself go, I’d have all sorts of cars in my garage! I wouldn’t say no to a Citroën C6, for example!