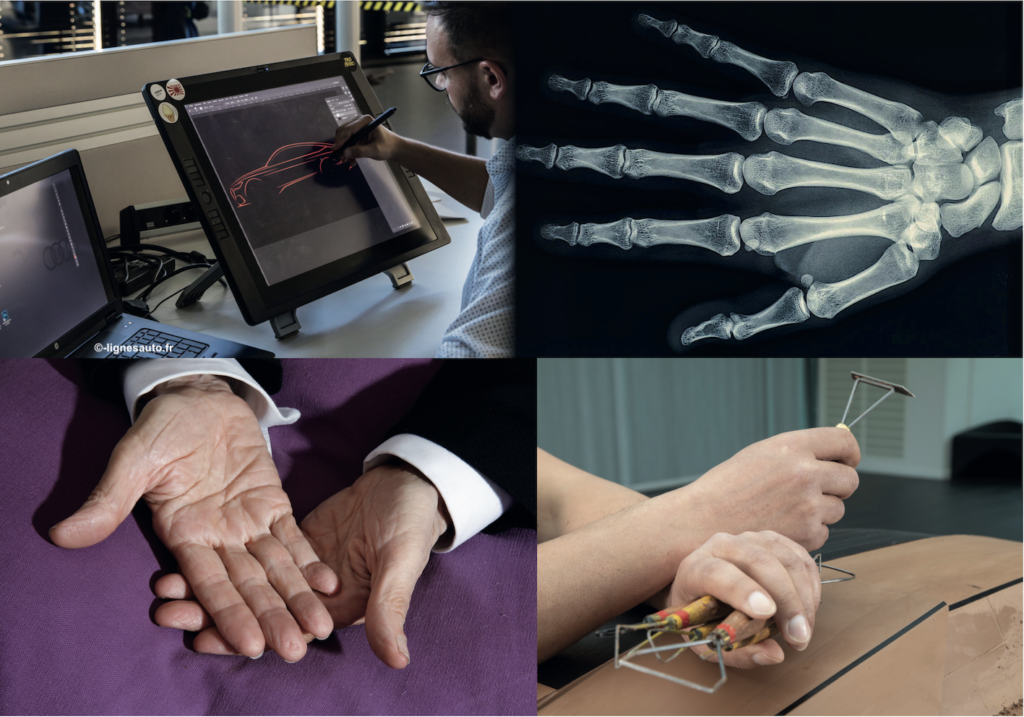

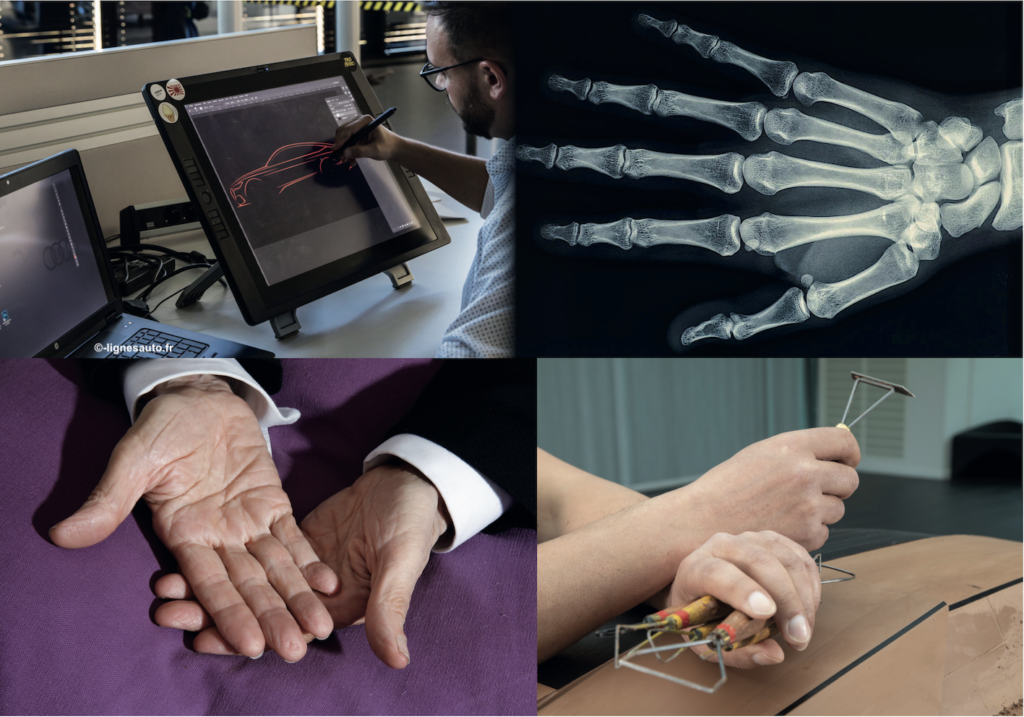

Ten fingers, twenty-seven bones per hand, that’s fifty-four for each designer. These are the basic tools available to young designers to express their talent. Add to that a bit of brains, passion and curiosity. And no doubt, a gift that enables them to handle this collection of bones with a light touch and succeed in sketching out their dreams. And ours.

When it comes to the hand, all designers are equal! Whether in terms of the number of metacarpals, trapezia, scaphoids, distals or proximals. And these fleshy, tapered, straight or curved fingers become the same tool for everyone. Of course, they are not the only expression of design talent. A professional pianist, a surgeon or any other profession where manual dexterity is essential sometimes has specific insurance to cover themselves against accidents. Not so for designers.

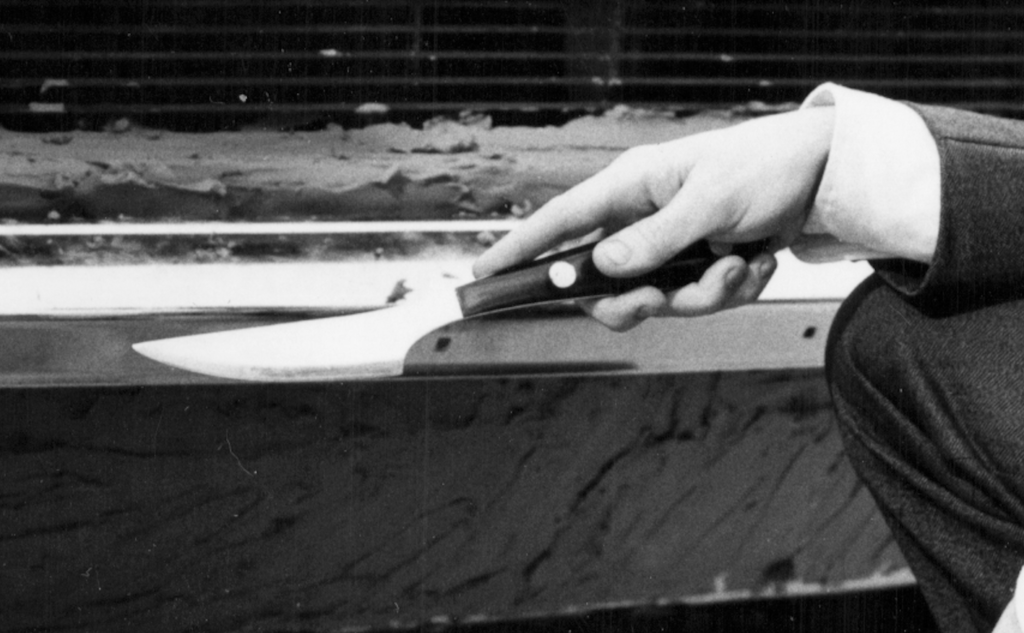

But when you look at the designers, your gaze will undoubtedly be drawn to their hands. This has happened to me many times, and the first ones that made an impression on me were those of Gérard Welter (1942-2018), former head of Peugeot styling. Paradoxically, these hands drew much less than those of his colleagues, because Welter, who came from a school for staff carpenters, only worked with volume and models. Not really by drawing…

Added to the materials that have been sanded, felt and sculpted over and over again, the passage of time has allowed these artist’s hands to develop a patina. Hands that have created automotive history. Others have left an even stronger mark on that history. In Paul Bracq’s hands, you can read about the epic design history of Mercedes and BMW.

Bracq, even as a senior manager, drew every day, and this was the basis of his training. No plaster dust here, but the elite of the Ecole Boulle and the beginnings of a great painter on the horizon. “I call myself a coachbuilder”, he likes to say, but more than sheet metal, it’s icons that his hands have sketched, from the Mercedes 600 to the Pagode, via the BMW Turbo concept car and the 3, 5 and 7 series of the 1970s. For years now, he has been focusing his energies on painting…

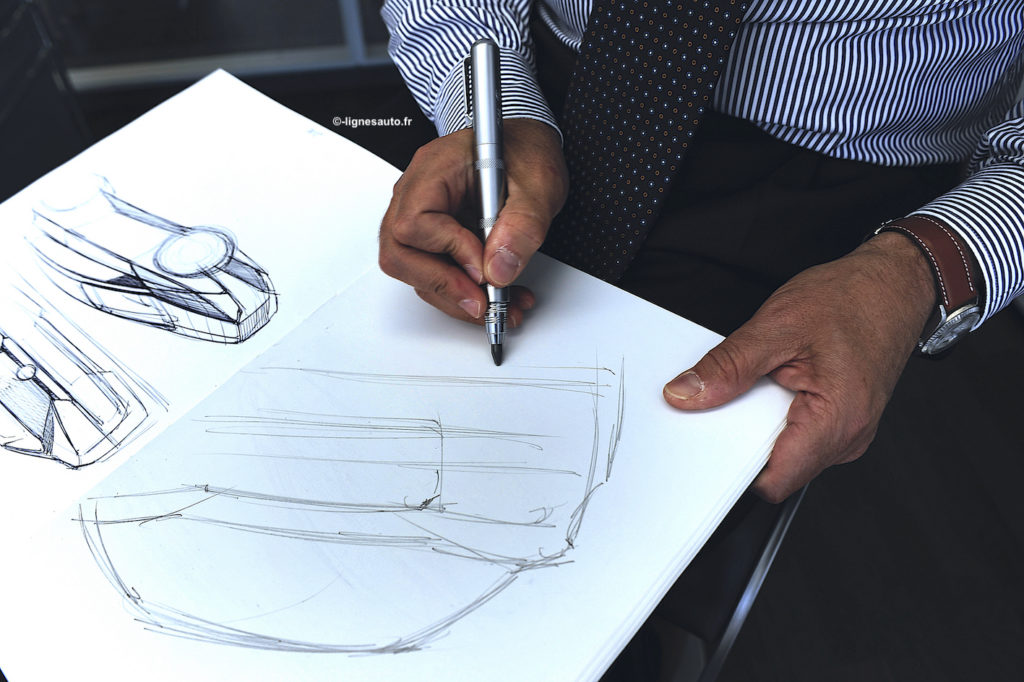

These hands should be protected by gloves. There are several kinds of designers: those who still draw, even at the very end of their careers, and those who no longer do. Too many constraints in terms of management. No more time… Or maybe they just don’t dare any more? Giorgetto Giugiaro and Walter de Silva took out their notebooks in front of me and accompanied their words, which I drank in, with drawings that I would gladly have taken home with me.

The ballet of their hands became inseparable from their words. As if the thought and genius of these giants of automotive design went directly from their brains to the tips of their phalanges. Like a continuous creative current. Their primary tool is simply the pencil. Or the Bic pen for others. Because the younger generation has not discarded this mode of expression that relies on paper. A form of paper said to date back to 105 AD and to have been invented by the Chinese, who have definitely followed us here…

The interviews are also used to read the gestures of those hands that twirl to accompany the words. Words that are sometimes not enough to understand the tension of a line or the muscle of a volume. Is it because of this gestural language that Italian designers have long had a considerable lead in car design?

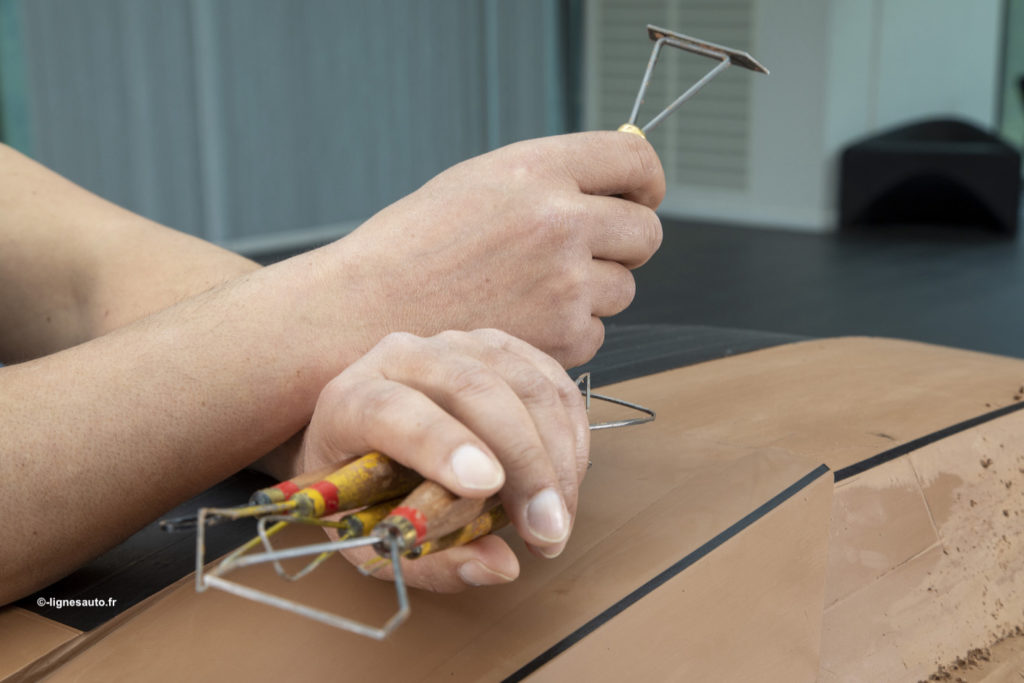

Among all the fingers present in this subject, I wanted to include those of a clay sculptor, the artist Slimane Toubal. This profession, even more than that of designers, relies above all on the work of the hands: pinching the smoothing ruler, gripping the cleaning brush, translating the millimetre that the eye wants to correct, kneading the still-warm clay with the thumb. In this way, the modeller translates the designer’s ultimate expression.

Slimane explained it very well for LIGNES/auto: “The relationship between the modeller and the designer is important. If you don’t understand what he wants, you can’t translate his design. It’s up to the modeler to explain that what he’s drawn doesn’t work in terms of volume, technical constraints or proportions.

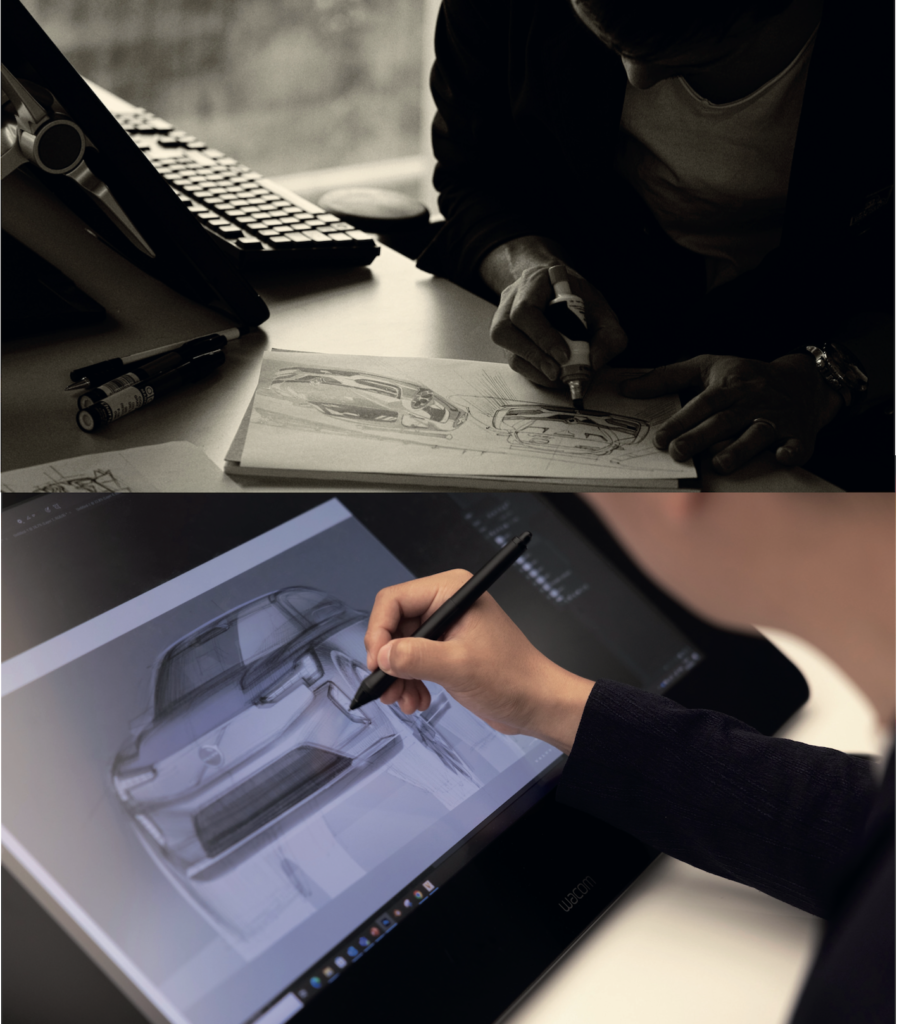

However, the physical modelling profession has lost a lot of ground in recent years, with the arrival of digital technology. So the physical designer has to supplement his skills with those of handling a mouse, as Slimane has done. “I have a lot more experience as a physical modeler, and that’s a handicap when it comes to establishing yourself as a digital modeler. It’s a shame, because a model who goes digital has real expertise in volume! They’ve mastered the proportions and have a real vision of the 3D model.

Designers and fashion designers have enchantment at their fingertips. And enchantment is more feminine, isn’t it? It seems that this profession is not very open to women. Slimane admits that “it’s true that there aren’t many in the modelling workshops. On the other hand, I’ve had a lot of female colleagues in Germany. They tend to come from pottery and ceramics backgrounds and they do high-quality work! “

Could it be that the female hand is ultimately more competent? Slimane doesn’t enter into this debate, but admits that “when I was at Audi, I discovered the quality of the models with clearances of around 0.5 mm for the interior parts, much finer than elsewhere, where we’re more in the millimetre or even 1.5 mm range. But the way all the manufacturers work remains the same.

And this modelling work is very physical, unlike the job of a static designer in front of his tablet. “Even if you work standing up, you’re always bending your knees, not to mention working on the underbody. The models are sometimes installed on jacks to raise them. “Yes, but during a rush, when we go from two or three modellers to six around the car, the model remains in a low position because you inevitably have a colleague working on the roof, and so you have to be on all fours to finish a rocker panel!”

It’s not just your hands that create the car of tomorrow, which ends up bringing creative people to their knees, exhausting them, like being born. So let’s show our respect for the fifty-four bones in our hands, which 3D and physical designers and modellers know how to master so much better than we do…

BONUS: dozens of phalanges!