‘Style without technique is sculpture, not a car!’ This quote, taken from the lengthy interview above with Gilles le Borgne, Director of Engineering at Stellantis until 2019 and then at Renault until 2024, sums up today’s theme: are design and engineering a good match?

The company that has won five ‘Car of the Year’* awards in 11 years was keen to share its experience. It has developed three major platforms** in three decades, providing insight into how design is integrated into the technological creation process of a new car.

*308 II in 2014 / 3008 I in 2017 / 208 II in 2020 / Scénic E-Tech in 2024 / R5 E-Tech in 2025.

*At PSA/Stellantis: the PFA in the 2000s, then the EMP2 in 2013, and at Renault: the AmpR Small of the R5 E-TECH below.

In the 1980s and 1990s, tensions were sometimes high between engineers and designers. It must be acknowledged that today, “designers integrate the idea of design in the technological sense of the term, and engineers recognise the importance of style. Thus, from the PFA platform of the late 1990s to today’s AmpR Small in the R5 E-TECH, via the EMP2, we have gradually moved towards an exemplary collaboration between style and technology, which now form a single team,” confirms Gilles le Borgne.

“Today, we have studio engineers who report to different departments depending on the organisation, style or engineering. They gather all the constraints and make them available to the designers. The designers then post their generic theme, based on their sketches, on this digital platform. The engineers and designers then work together to find a compromise that respects both the design theme and the technical constraints.“

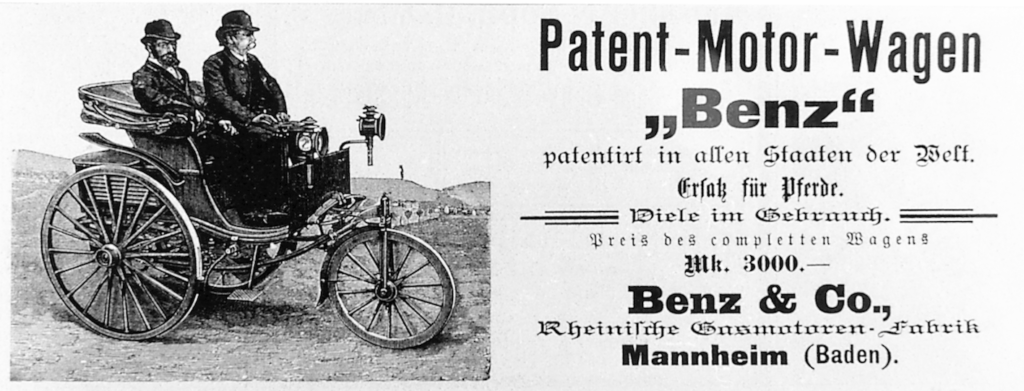

So everything is fine then? Today, yes, for the most part… But that hasn’t always been the case! Designers rarely have engineering training. And engineers don’t necessarily have an artistic flair, which isn’t required of them anyway. Are they compatible? Let’s quickly return to the roots of this age-old problem of coexistence. And so we return to the origins of the automobile in the mid-1880s. It was engineers who, alone, advanced towards the creation of the automobile: Gottlieb Daimler, Armand Peugeot, Carl Benz (below), Wilhelm Maybach and many others.

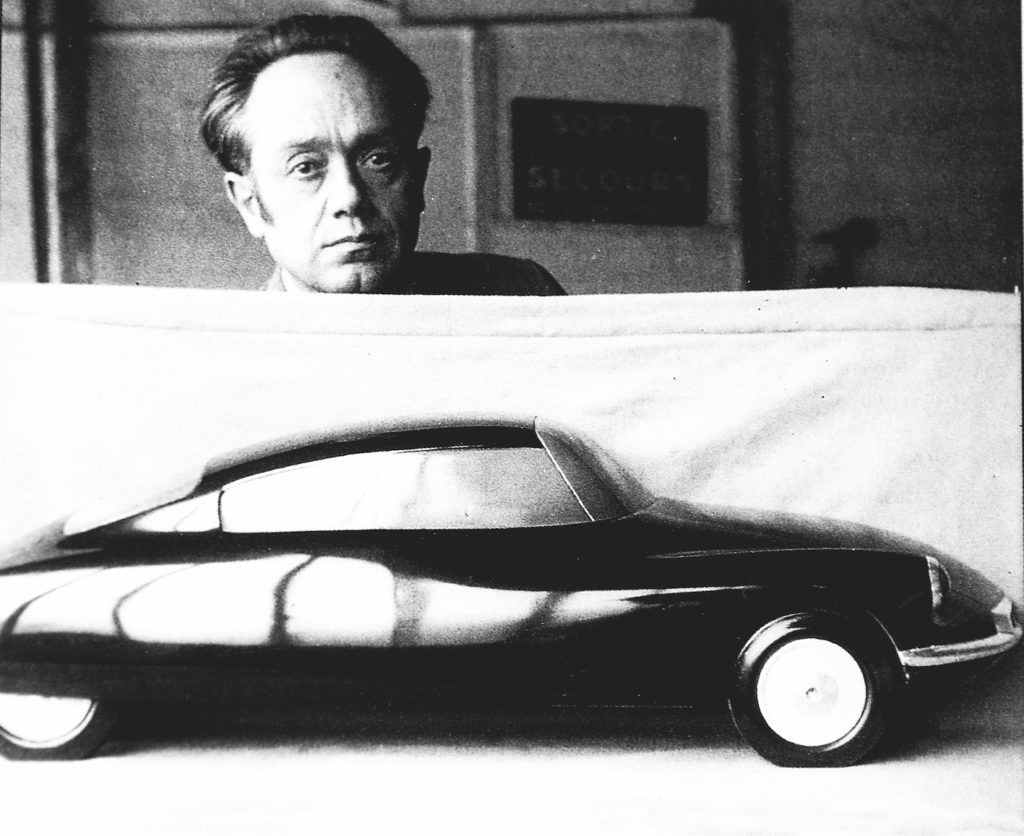

Should we give them credit? “From the end of the 19thcentury to the beginning of the 20th, design focused on functionality and technology. Aesthetics were secondary, if not completely non-existent!” In the 1920s, the famous Roaring Twenties, design began to be integrated into everyday life. “Then, the balance between form and function was highlighted through aerodynamics. This was a major milestone. In the mid-1950s, it was of course the Citroën DS that symbolised the alliance between the worlds of engineering and design.“

The Italian Flaminio Bertoni reigned supreme over Citroën’s designs at the time. He was practically alone. On the other side of the walls of Citroën’s design department on Rue du Théâtre in Paris, engineers were working on their own, creating flamboyant innovations. Everyone was doing their own thing, so to speak. During the 1970s, designers were considered on a par with engineers. But they were sometimes mocked by the latter. Gaston Juchet (1930-2007), then head of design at Renault, recalled that for the R30 programme (1975 – design by Gaston Juchet below), the technical department asked him to raise the waistline of his design “because sheet metal is cheaper and weighs less than glass.”

In terms of salary, stylists at the time were light years away from those who would become designers and gradually join the management committees of certain major automotive groups in the 1990s and 2000s. Design then began to play a more important role in decision-making. But remember the opening sentence: ‘Style without technique is sculpture, not a car!’ And to produce a car rather than a simple sculpture, it was sometimes necessary to speak up!

Gilles le Borgne acknowledges that at PSA, under Jean-Martin Folz (CEO from 1997 to early 2007), “things didn’t always go smoothly with Gérard Welter, Peugeot’s design director (above), with whom I worked from 1997 on the design of the PFA.” It was during this period, and particularly with the Peugeot 407 (below), that Gérard Welter confided in me that “we had proposed models with a much shorter front overhang, but during the design phase we were asked to add a few millimetres here and there. It’s a shame, because this car really has character, but it’s got a pretty big nose! It’s the eternal problem of reconciling technology and style. Many cars have suffered from this.“

Things are heating up, but Gilles le Borgne has an unanswerable explanation. “I am very familiar with the sequence of events surrounding the 407 in 2004. It was based on the PF3 platform for upper-segment saloons, which was introduced with the first generation of the Citroën C5 in 2000. Under Folz, this PF3 was frozen, we weren’t allowed to touch it! And so, yes, the 407 suffered as a result.”

With the 307 Car of the Year 2022, which inaugurated the PF2, Gérard Welter nevertheless asserted his ideas right through to the production stage. He pushed the theme of a semi-high saloon with a very steeply raked windscreen that plunged far forward over the bonnet. “Gérard pushed us very hard with his 307. He pushed the engineers to their limits with a windscreen that was so far forward that there was no visor, no air/water separation zone, and all the technical components were cantilevered above the engine. The engineers really had to rack their brains to design it all and come up with the super-advanced windscreen that the designers wanted! ” So yes, designers also know how to impose their ideas when it’s technically feasible. However, Gilles le Borgne points out that “during my career, I’ve worked closely with at least twelve designers. And I’ve always defended their ideas, contrary to what people might think, because I know that style is often the reason people buy a car!“

Gérard Welter was somewhat distrustful of engineers. He therefore had to use stratagems to get his ideas across, even if it meant crossing certain lines. Much to the delight of the designers whose ideas he defended. Less so for the technical team, as Gilles le Borgne recalls. “At the time, I was a young, rigorous engineer and knew little about the world of design. I started with the Citroën C3 (project A8) in 2002, with Donato Coco, head of small car design, and Oleg Son, the designer. This project was part of the A806 programme, along with two other derivatives based on the new PFA platform: the Citroën C2 (project A6) and a small Peugeot that was ultimately abandoned, project A0.”

“Here we are on this programme on the eve of a general presentation of models of the Peugeot A0 project with Frédéric St-Geours (Peugeot brand director at the time). The day before the presentation, we agreed on the milestones, validated the dimensions of Gérard’s team’s proposals, and agreed on the style of the windscreen position, wheel arches, wheel diameters, etc. to see if it fit within the PFA specifications. But the next day, the official presentation day, we were in for a surprise: Gérard had changed the models overnight! They were completely different! He had presented other models with completely different dimensions… We had no choice but to restart the feasibility studies and lost a huge amount of time.“

An exception to the rule? No, Gérard defended ALL his projects and sometimes went beyond the limits so that, in the end, something would remain. “A little later in the development of this A0 programme, we presented two models, one rather technical that reflected the stylistic intentions – in other words, a feasible model – and the model wanted by the designers, but not feasible as it stood. It was largely inspired by the 307 that Gérard had just finished, and he had pushed the forward windscreen to the extreme in his proposal. Frédéric Saint-Geours was quite enthusiastic, but during the meeting, I explained that with such a silhouette, the engine would have to be removed to change the spark plugs, which were inaccessible under the windscreen! Saint-Geours turned to Welter and said, ‘I think, Mr. Welter, that we’re going to have to move the windscreen back.”

In those days, engineering and design had quite logical differences. But at PSA, they seemed more pronounced at Peugeot than at its cousin Citroën! “It’s true that it was easier with Donato Coco (above) at Citroën. With him, it wasn’t trench warfare like it was with Gérard. But don’t get me wrong, we went on to make a lot of very good cars with Welter, notably the 207, which was a huge hit, and the first 308.“

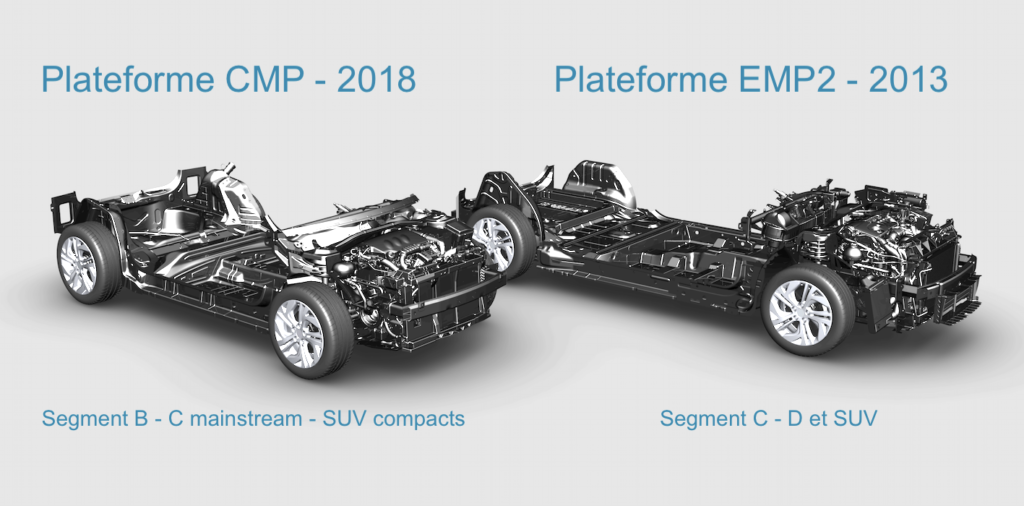

With the arrival of Jean-Pierre Ploué in the 2000s, did the coexistence of engineering and design become more pronounced? For Gilles le Borgne, “we mustn’t forget that right from the start, with the PFA and the PF2 and PF3 of the Folz era, we were already taking into account generic styling requirements, such as overall proportions and wheel diameters, for example. But it was much less structured than what we did ten years later with the EMP2 platform, which I was responsible for. The style requirements were all included in the initial specifications, so the possibility of achieving the right proportions desired by the designers was set out in the very first specifications, alongside dynamic performance, costs, technical specifications, etc.“

The word ‘platform’ appears frequently in this article… This is logical, as this architectural and technical framework (*see Bonus at the bottom of this section) forms the basis for the design, with all its possibilities but also its limitations. At PSA, after the Folz era, Gilles le Borgne discovered that of Christian Streiff. (2007-2009). Gilles proposed structuring the range on the basis of two platforms instead of the previous three. At the end of the 2000s, the famous EMP2 platform (“my best work as an engineer“) was under study under his responsibility, and this design period further linked the two worlds of engineering and design.

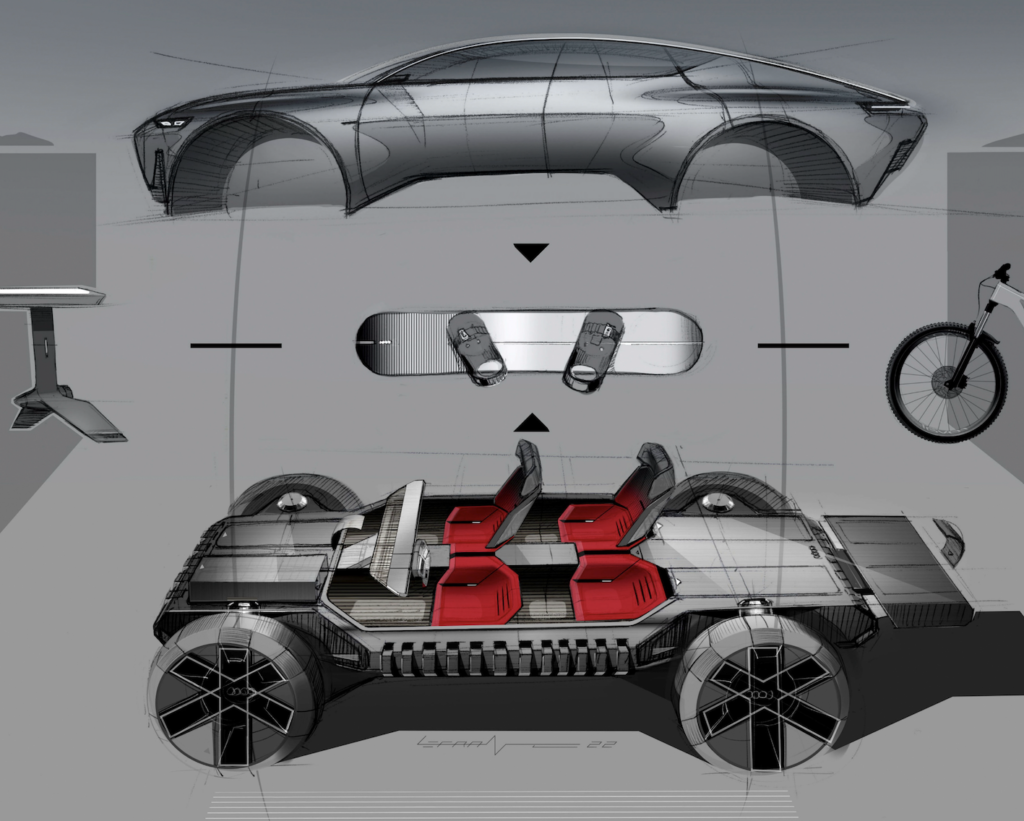

“I was already head of preliminary design with extensive technical expertise in preparing the EMP2. Style was at the heart of the project. We were working in Robert Peugeot’s team, and Welter and Ploué were responsible for styling. It was very new because we had anticipated ten silhouettes that didn’t yet exist, capable of being produced on this modular platform. Right from the preliminary design phase, we kept all the styling requests up to date and regularly produced polystyrene models. We held regular reviews with the styling managers and Robert Peugeot. Reducing the overhangs and lowering the height of the bonnet were just some of the changes reviewed with the design team to provide them with a single modular platform that could be adapted to their proposals for saloon cars, SUVs, MPVs, etc.” The Peugeot 308 II above and the Citroën C4 Picasso II MPV will be the first models to feature it in 2013.

This period also marked a period of upheaval for Italian design consultants working for Citroën and Peugeot. In 2004, Robert Peugeot decided to end collaborations with Giugiaro, Bertone and Pininfarina. Was this because these consultants were ignoring the specifications set out in the various design briefs? “Not at all. In fact, it was quite the opposite. I know this because I worked with Giugiaro on the C3 Pluriel project and I was at the meeting when these collaborations were terminated. I often flew with the group to Turin to visit these Italian consultants with Vincent Besson or Bruno de Guibert. It was the establishment of international design studios within PSA, particularly in Latin America and China, that made Robert Peugeot think. He decided that these internal PSA studios could compete for the group’s projects. Welter and Ploué pushed this approach…“

However, at Renault, the discourse was quite different in the 1980s. Collaboration with Giugiaro was intense. It gave rise to the Renault 21 (1986) and Renault 19 (1988). Renault’s designers told me at the time that they had to go back to Giugiaro’s models to bring them back into line with the specifications. Gilles le Borgne tempers this by pointing out that, at the time, “specifications were not supposed to exceed three pages! It wasn’t until the advent of CAD, particularly with the 206 programme, that all that changed.” As for Giugiaro and Renault, the affair ended with the replacement of the Supercinq by the Clio in 1990: the in-house design team won the project!

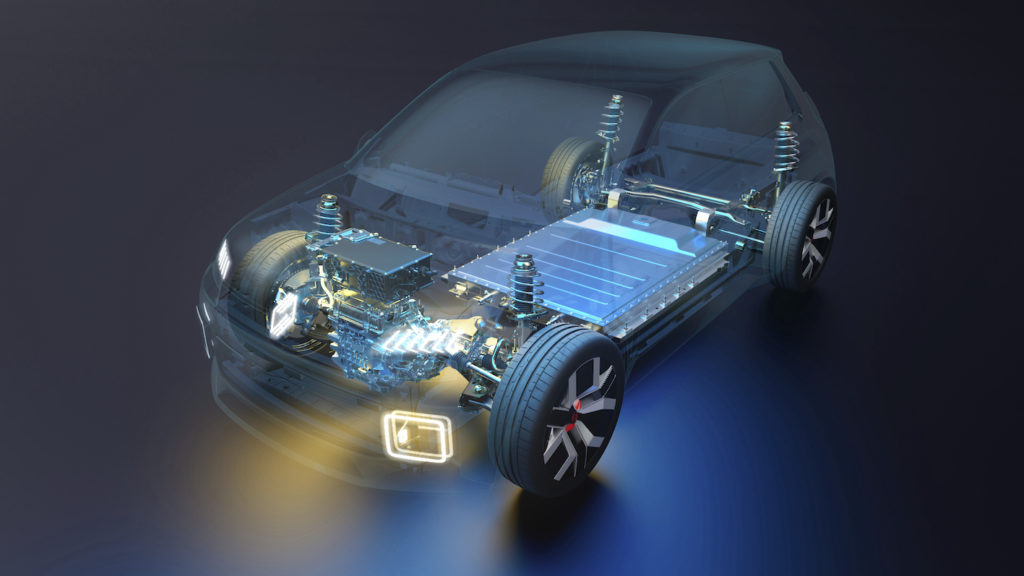

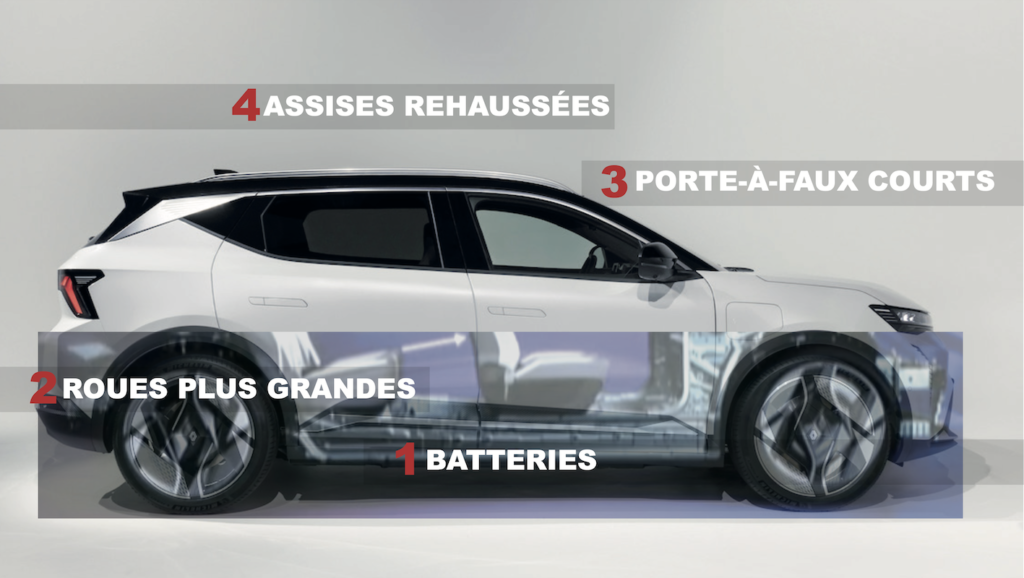

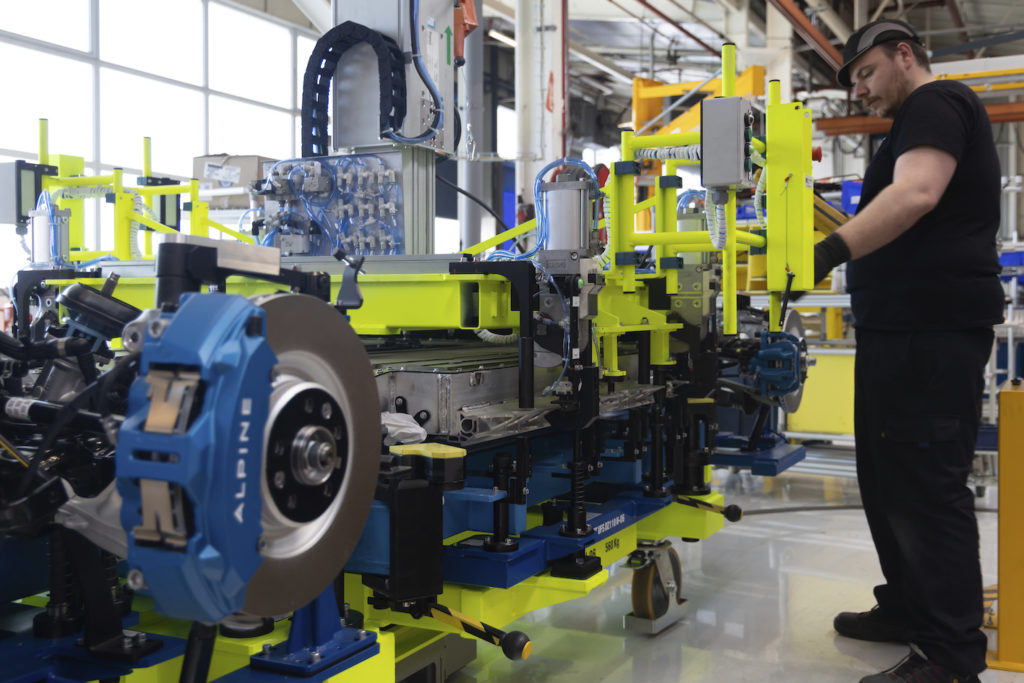

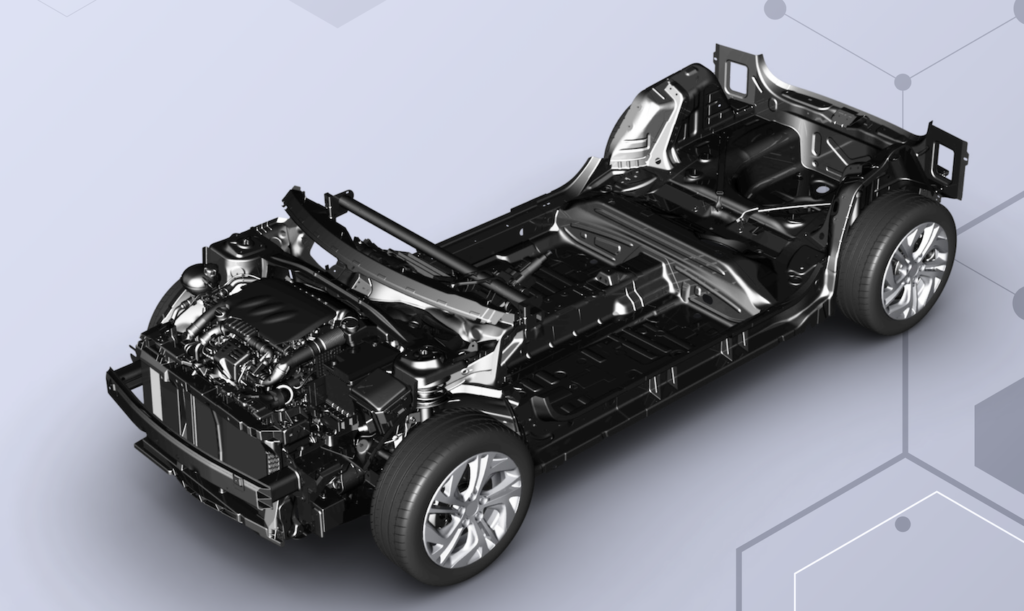

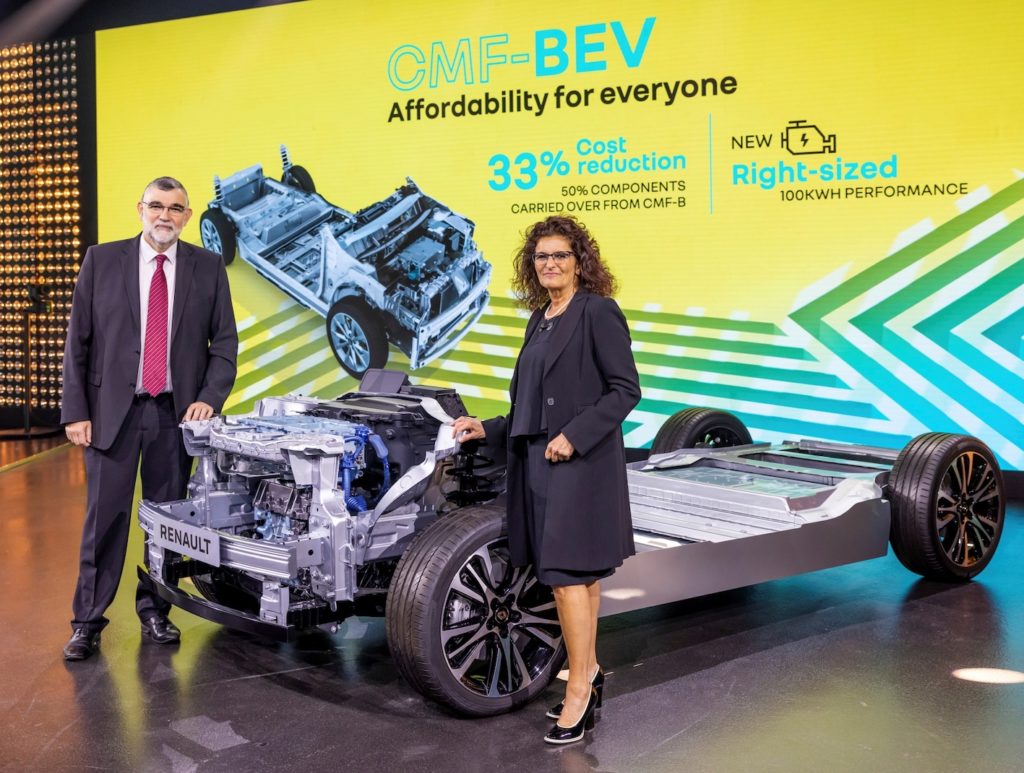

But let’s get back to our platforms and the silhouettes designed by designers to dress them up. In 2025, when we hear this term, we often think of a 100% electric platform (above, the Renault Scénic). Has it become the Holy Grail for designers freed from heavy constraints with its flat floor and reduced overhangs? Not necessarily, according to Gilles le Borgne. “Obviously, the overhangs are contained, but the problem designers face is that with the battery pack between the front and rear axles, you end up with an extremely long wheelbase and a “dachshund” effect that needs to be avoided. Then there’s the wheel diameter/height ratio, which has to be handled carefully because the battery raises the floor and can therefore increase the height of the car.” Below, the 100% EV platform of the new Alpine A390 crossover in the Dieppe factory.

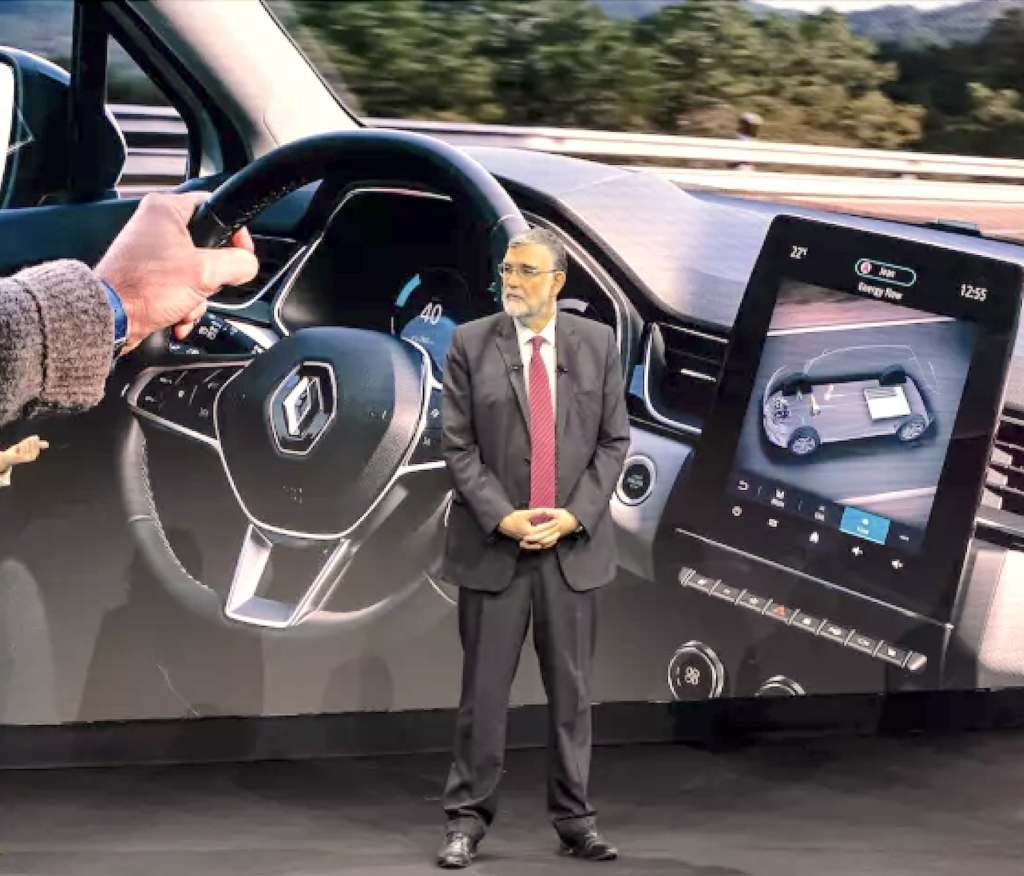

And if you think Gilles le Borgne has forgotten about the R5 E-Tech, think again… He’s well placed to talk about it, as he’s the man behind the design of this electric R5. “For this model, we kept the front frame and architecture of the Clio with a lot of carry-over (shared parts), which reduced the car’s manufacturing cost. We were able to shorten the overhangs, particularly at the front, by optimising the cooling front end.” The Renault 5 E-Tech is a perfect example of an engineering and design team working hand in hand, as Gilles le Borgne explains.

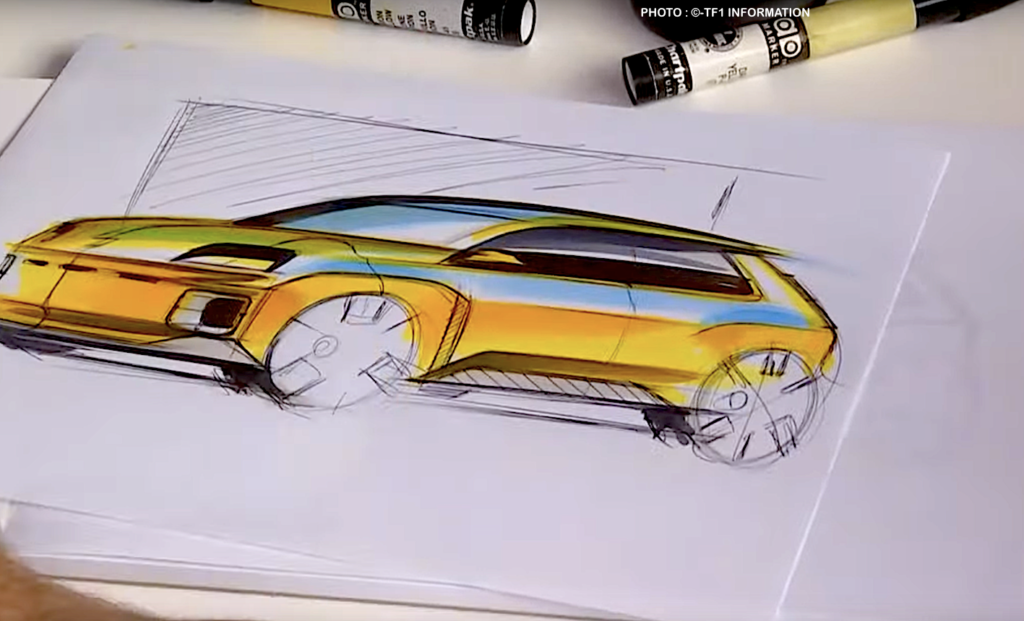

“The story is well known. Luca de Meo arrived at Renault in the summer of 2020, while I had joined the company in January after leaving Stellantis. In September 2020, we had a design meeting and we were both quite dismayed to see that the product plan only included small, low-profit cars! Then Luca said, “Stop, let’s halt everything,” and saw the orange model (above) of the R5, which he absolutely wanted to include in the plan as a priority. The technical teams at the time said it was impossible. And there wasn’t much appetite for revivals on the part of the former CEO.“

“From there, I explained to Laurens van den Acker (Renault Group Design Director) and Gilles Vidal (above), who later became head of design for the Renault brand, that I could make this car, but not in the dimensions of the model, which was 3.80 metres long. It was far too short. I told Gilles, ‘I’m going to blow up your model until it fits on a platform based on the Clio’s CMF-B, but dedicated to EVs. And that’s what we did. Enlarging the ECHO model of the R5 wasn’t a problem, because the eye reads proportions, not absolute values. In the end, the initial proportions were strictly preserved, with a length limited to 3.92 m and a height of 1.50 m.(1.46 m for the ECHO model)”

And for those of us who are calling for a thermal/hybrid R5 E-Tech, can we believe the designers who tell us that this would be impossible because it would distort the proportions? “If you’re just talking about a styling issue, the answer is yes, the styling would have to be modified with a higher bonnet and a longer front overhang, if only to accommodate the combustion engine cooling system. But we had this debate internally in November 2020, we even carried out studies, but Luca said “no” to the hybrid R5. He argued that there was already a combustion engine/hybrid range with the Clio… and he’s the boss! ” I thought I detected a hint of regret in my interlocutor’s voice…

This R5 E-tech is therefore the perfect illustration of what has become the reality of the 2020s: a fusion of engineering and design. Gilles le Borgne explains that “back in the days of Gérard Welter at Peugeot and Arthur Blakeslee (head of design at Citroën from 1987 to 1999), cars were designed over a period of at least five years. We had time to debate! Today, they are designed in three years, and even two years for the future Twingo. We no longer have time for endless debates! Every ten years since the 1990s and the advent of digital tools, style has gradually become more important in its integration with engineering. The example of the R5 E-TECH is a good one: we started with a styling theme to design the platform and managed to make this car from a model that was ‘lying around’ in a corner of the studio. A model that was then just a sculpture.” And we understood: “Style without technology is a sculpture, not a car!“

LIGNES/auto also has a bilingual Facebook page for news: https://www.facebook.com/lignesauto/

BONUS: WHAT EXACTLY IS A PLATFORM ?

According to Stellantis, a platform is the (modular) base of the vehicle that is at the heart of the design and manufacture of new models. It brings together all of the vehicle’s functions, except for those specific to the body style. The platform therefore comprises the underbody, the suspension, the powertrain adaptations and the core of the electrical and electronic architecture. Together, these components account for more than 40% of a vehicle’s cost price.

BIO EXPRESS GILLES LE BORGNE

Gilles le Borgne has not yet completely retired from business. He will even be on Valeo’s board of directors from January 2026. “Since I left Renault in 2024, you can’t imagine how many offers I’ve had!” It’s true that his most recent responsibilities as engineering director at two major French automotive groups are impressive. However, nothing predisposed this graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure des Céramiques Industrielles to this career. “When I joined PSA in the late 1980s, I did technological and scientific research related to materials. I then spent part of my career in research management. I developed composite parts made of magnesium and aluminium.“

He then worked on a little-known project from 1994 to 1997: “We rebuilt a Citroën ZX from the ground up with the aim of making it lighter in every way. I learned my trade here, because I tackled every aspect of the job, including architecture, acoustics, crash testing and road handling, using innovative methods. I applied my knowledge of physics, which was unheard of at the time.” The head of synthesis then entrusted him with the design of the first PSA platform of the modern era: the PFA, for which he became design manager. Then came EMP2 in 2013 and his departure from Stellantis in 2019 following a disagreement with Carlos Tavares. And the grand finale with the turnaround of Renault and the electric platform for the R5-R4-Micra and Alpine A290…