From the 504 in 1968 to the 604 in 1975, via Project J, the history of Peugeot’s top-of-the-range models in the 1970s was not a smooth ride. Let’s take a look back at the 1960s, when the 404 was to be replaced by a high-end version of Project J (see our article on this sprawling Peugeot here: https://lignesauto.fr/?p=43765 ), which would effectively lead to an upgrade of the 504 saloon.

For the latter, Peugeot devised the E22 programme in March 1969, which slightly modified its aesthetics. The 504 E22 was equipped with the V6 engine then under development following the Peugeot-Renault agreements signed in 1966. This 504 V6 saloon would therefore complete in 1972 (estimated date of its launch) a solid range in anticipation of the 1970s: the future 104 (1972), the brand new 204 (1965), the upcoming 304 capable of competing with the European mid-range, the future J23 family saloon (rear-wheel drive and front-wheel drive, saloon, coupé, estate, etc.), the four-cylinder 504 and the ambitious 504 E22 V6.

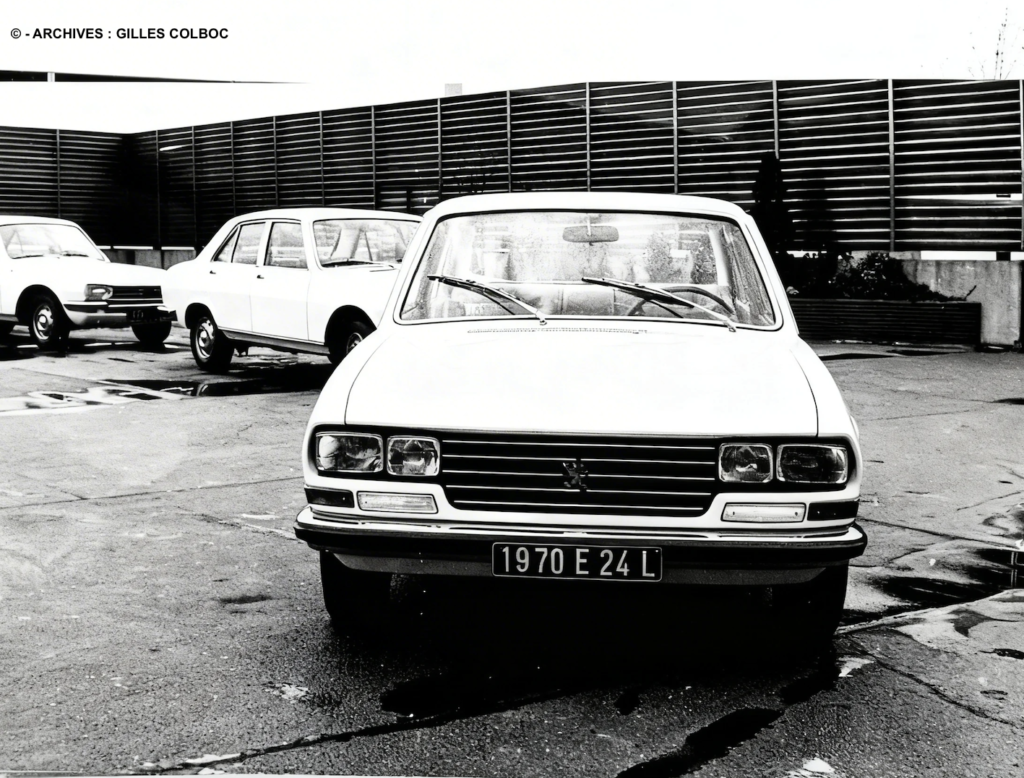

Ambitious, yes, because Peugeot imagined that this V6 variant would be the most popular of all the 504s. But plans cannot predict the vagaries of a manufacturer’s life. And it began with the famous Project J, which, due to its complexity, was ultimately abandoned and transformed into a remodelled 304: the 305 of 1977. This abandonment automatically brought the Peugeot 504 V6 saloon down from its pedestal to its rightful place. The E22 programme disappeared from the product plan. It was replaced by the E24 programme, which was finalised in December 1970, as shown above.

This was a truly high-end model, not just a 504 with a new engine. However, even though Sochaux is quite far from Auvergne, every penny had to be saved on this project. The E24 would therefore retain the central body of the 504 – and therefore its wheelbase – combined with major modifications to the front and rear. A remake of the 204/304 duo, in a way. To clearly position the E24 in the European high-end market, Peugeot planned two engines in December 1970: a V6 and the V8 from the major joint project with Renault, which was still ongoing at the end of 1970. So no four-cylinder engine for this project.

The first models were then produced in quick succession and were effectively a redesigned version of the 504. However, some of the aesthetic innovations of the J coupé (which had not yet been abandoned at that point) were incorporated into one of the models, such as the black grille with four headlights, two rectangular and two square. The body of the 504 was partly retained, but in April 1971, the E24 specifications stated that the wheelbase would ultimately be increased by 6 centimetres, with the front overhang increased by 4 cm and the rear overhang by 6 cm. The saloon would then be close to 4.70 metres long (the future 604 would be 4.72 metres long).

In March 1971, the V6 and V8 remained in the specifications according to official notes. In terms of tools, Peugeot offered designers the opportunity to create a new side panel, new rear doors and a new roof. But the E24 had to retain the front doors and windscreen of the 504. Ultimately, today’s Stellantis ‘carry-over’ is merely a descendant of what was happening in the 1970s. Without spoiling the ending, let’s just say that the 604 retained the front doors of the 504.

In 1971, the final design model (above) had two different sides: one on the driver’s side with only two side windows, and the other on the passenger side with three side windows. According to an internal memo, the latter variant was preferred. The idea was to market this E24 in 1974. Obviously, no one could have foreseen the geopolitical turmoil that would ensue with the 1973 oil crisis… We do not have enough information to determine the origin of this model of the chosen style.

It is clearly very similar in style to what would become the 1975 Peugeot 604, known to have been based on a design by Italian designer Pininfarina. However, its grille was directly inspired by the work of Gérard Welter’s team on the J coupé, which never saw the light of day. The question remains, even if we consider Gérard Welter’s comments in the book dedicated to him, in which he clearly states that Pininfarina visited Peugeot’s studios without any problem (*see note at the bottom of this post).

The E24 project, originally designed on the basis of a 504 formatted for the high-end market, would therefore retain its V6 (the PRV) but abandon any notion of offering a V8, which was stillborn. In 1975, the 604 finally arrived on the market below, fulfilling much of the E24’s specifications, particularly with its connection to the 504 (front doors). A note dated 18 July 1975 clarified Peugeot’s strategy for its two high-end offerings.

The 504 remained in the E-segment saloon car category (project E), while the 604 was at the top of the range, defined by the letter H, which again corresponded to the European segment and not to project H from 1966-68, a joint programme between Peugeot and Renault. The ageing 504 gave rise to the E’ programme (project E30) for the 505, which in 1979 replaced the venerable saloon launched in 1968, once again with the help of Italian consultant Pininfarina (below). Four years later, with the 205, the Bouvot-Welter team would win the day in spectacular fashion.

The oil crisis obviously had an impact on sales of the fuel-hungry 604, as well as its rival, the Renault 30. Nevertheless, Peugeot produced more than 153,000 units, which was more than the 136,000 Renault 30s registered until the Renault 25 was launched. The latter would remain the last successful French saloon car, with more than 780,000 units sold until 1992…

Archives, documents and information: Gilles Colboc

*Gérard Welter explained his relationship with Pininfarina in his book WELTER, L’AGE D’OR DU STYLE PEUGEOT (The Golden Age of Peugeot Style), published by Éditions Roger Régis: “When the Farinas came to visit us, they had access to all our offices and wandered around our premises. Renzo Carli and Sergio Pininfarina would tour the design offices, look at our designers’ studies, observe the models and then go home. It became unbearable for me! I managed to convince Paul Bouvot to put an end to this type of visit.”