“A Michelin tyre museum? A gummy idea...” You’re probably thinking that “if it’s just to see tyres for two hours, it’s not worth it.” But l’Aventure Michelin is anything but! Maps, bicycles, microscopes, amazing cars, games, toys, tyres (all the same), unusual objects, milestones and signs, the future as much as the present, the past… put through the mill thanks to surprising archives… The Michelin Museum isn’t called ‘Michelin Adventure’ for nothing. It is one, and a fascinating one!

The idea for the museum dates back to 2004 and was originally the brainchild of Édouard Michelin (1963-2006), who wanted to “share with everyone the Group’s vision, as expressed by its brand signature: a better way forward“. Set designer Gilles Courat explains in the Michelin Adventure bilingual book available from the shop (€14.90 for everything you need to know about Michelin, you can’t refuse) that visitors are taken on “a chronological and thematic journey punctuated by surprises and unexpected islands. Each time, visitors are encouraged to move, touch, listen, look and smell“.

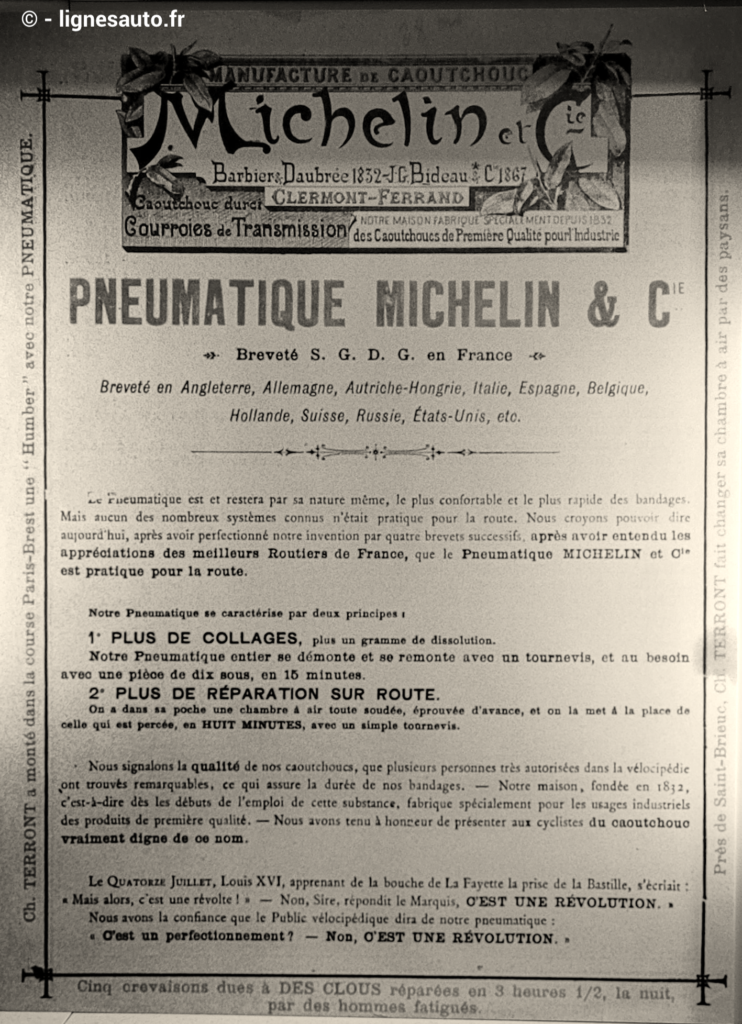

Ordinarily, a visit based solely on a chronological theme might seem off-putting. Michelin, from the mastery of rubber to the tyres of the year 2030, is all about different technologies, machines ranging from bicycles to the moon car of tomorrow, and exceptional men and women. First of all, there was the brilliant idea of “driving on air“. The Michelin brothers – Édouard and André – were not only inventors, they were also advertising ‘propaganda’ men. They organised cycle races to prove the merits of their demountable tyre. Charles Terront won the Paris-Brest-Paris race organised by Le Petit Journal in 1891 in just three days and three nights. The runner-up, who rode on traditional glued tyres, arrived… 8 hours and 27 minutes later. More than 10,000 cyclists adopted Michelin tyres the following year.

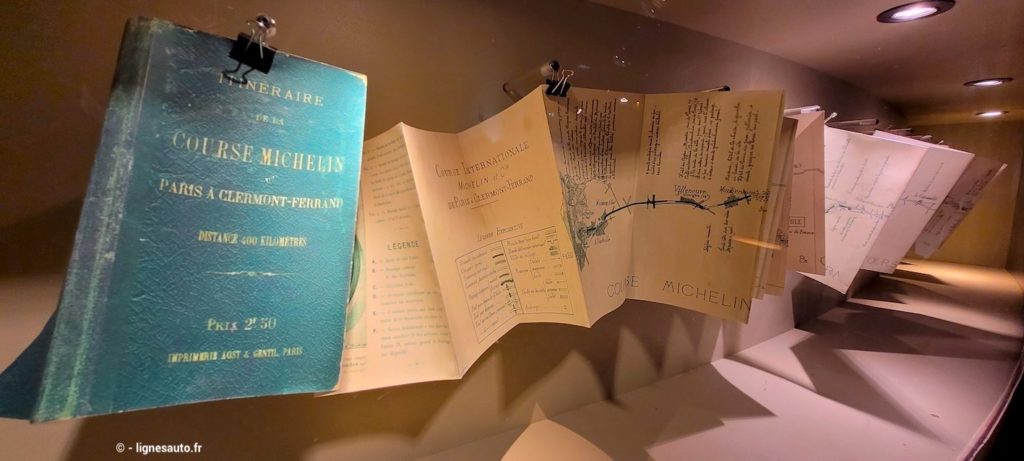

One year after the Paris-Brest-Paris race, the Michelin brothers are organising another between Paris and… Clermont-Ferrand. All the cyclists were equipped with removable Michelin tyres, so to spice up the competition, Édouard Michelin sowed nails along the route to prove once and for all that it was easy to repair a Michelin tyre and still be very fast on the road. Henri Farman won the 396 km race in 17 hours and 52 minutes.

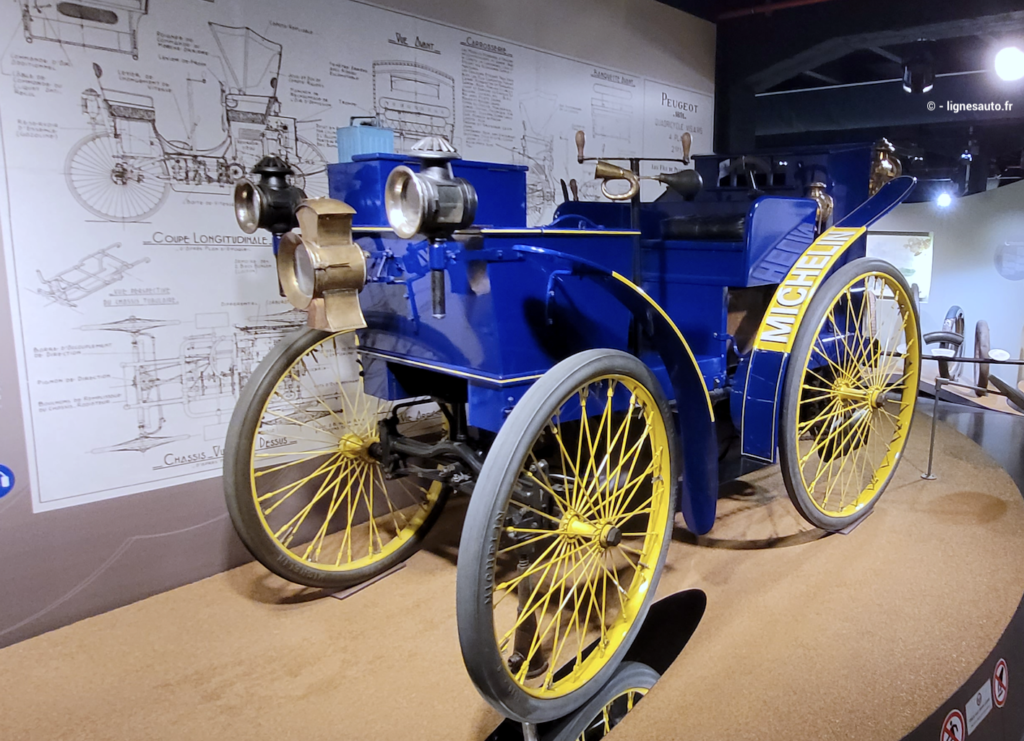

Above, it’s just a short step from the bicycle to the car. In 1895, the Éclair was based on a Peugeot chassis with a Daimler engine and was the first car in the world to be fitted with air-filled tyres. On 1 May 1899, the Michelin brothers continued their work and fitted the ‘Jamais contente’, the first electric car to exceed 100 km/h, with Camille Jenatzy at the wheel.

So as not to reveal everything about this fascinating visit, we won’t go into the tyre-making process, which is explained twice during the tour in a didactic way, supported as much by videos as by very explicit models. You won’t come out of this place as stupid as you went in! L’Aventure Michelin looks back over the years of tyre development, with some surprising features. The aviation period is also covered, not forgetting that the manufacturer would evolve at the same time as the burgeoning car industry.

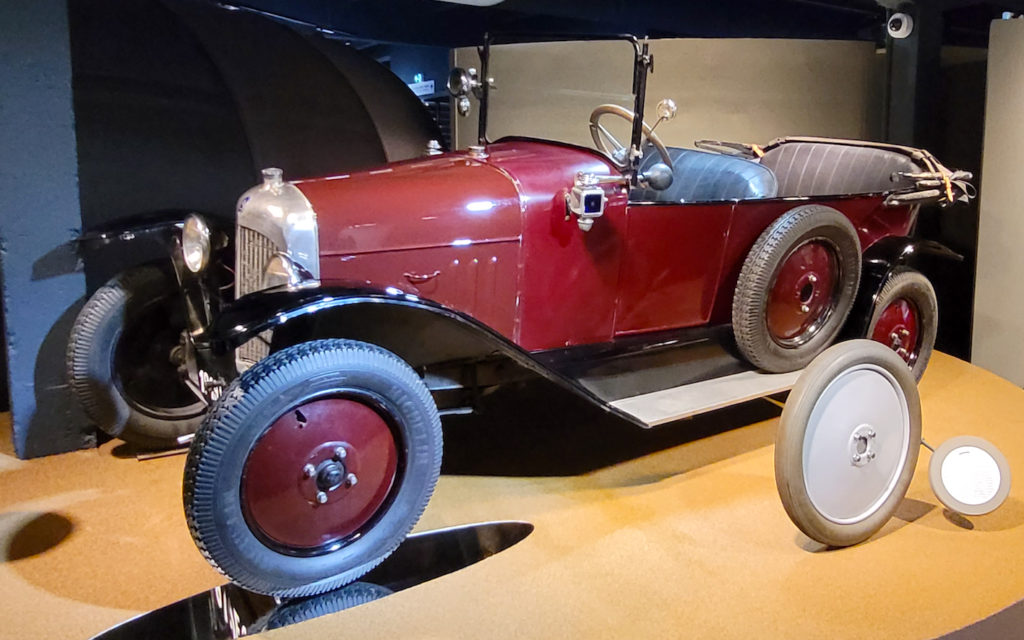

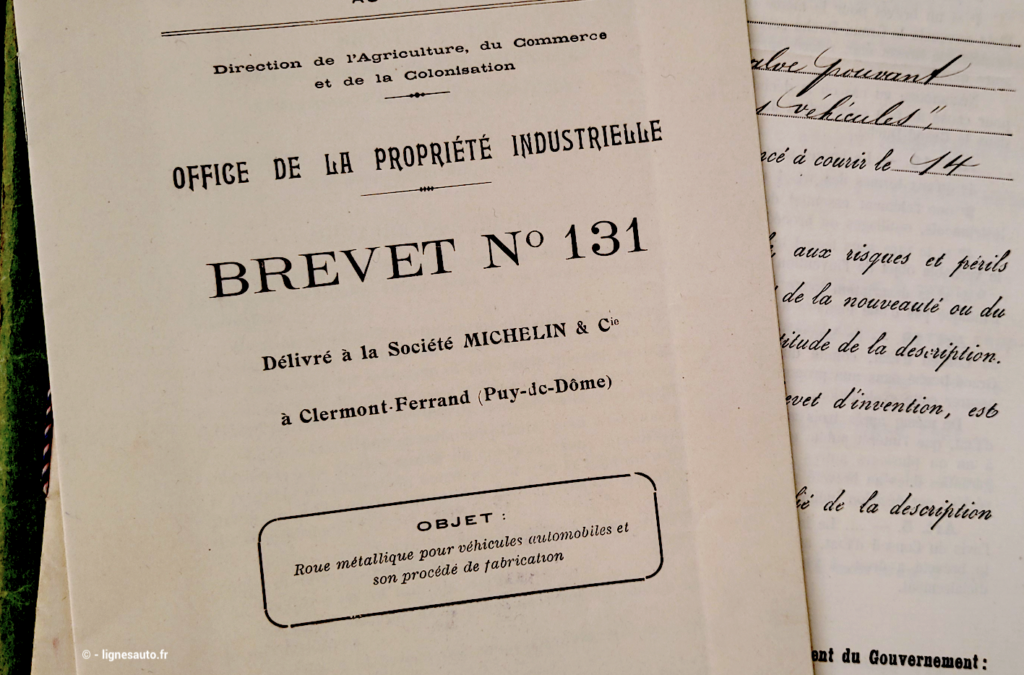

One of the great French industrialists was, of course, André Citroën. He remained at the head of his company for just sixteen years (1919-1934). But that was enough to create a myth! His first model, the Type A of 1919, was the first European car to be sold with a rare feature: a spare wheel. The Citroën takes pride of place on the tour. Connoisseurs will be moved to recall that it was Michelin that took over the Citroën reins at the end of 1934. It should be noted that this spare wheel was made possible by a Michelin patent dating from 1913 for a steel wheel that could be fitted quickly, thanks to the self-centring studs on the hub attached to the axle. A simple system that led to the idea of the famous spare wheel…

Ten years after the Citroën Type A was launched with Michelin tyres (and a spare wheel), the company adapted the tyre to the rail! It was a real revolution, not only in terms of comfort, but also in terms of endurance and safety, with more effective braking and higher speeds. In 1931, the first trip by a Micheline with passengers was made between Paris and Deauville. In less than ten years, more than 130 Michelines were built.

Like all European and then global companies, the war that broke out in 1939 deprived Michelin of business… Well, not quite. During the war, 80,000 trailers designed by Michelin were manufactured in Clermont-Ferrand to help families in their daily lives. During this period, the factory also manufactured 132,000 pairs of sandals, 30,000 wood-burning stoves and 23,000 pushchairs!

Another branch of Michelin’s business is signposts and road maps. During your visit, you will discover how maps are produced today using modern cartography methods. Before the First World War, Michelin distributed more than 30,000 ‘Merci’ signs to the communes of France, to be placed at the entrances and exits of towns and villages. They asked motorists to slow down and, above all, showed the full extent of the dangers of the road in the early days of the motor car.

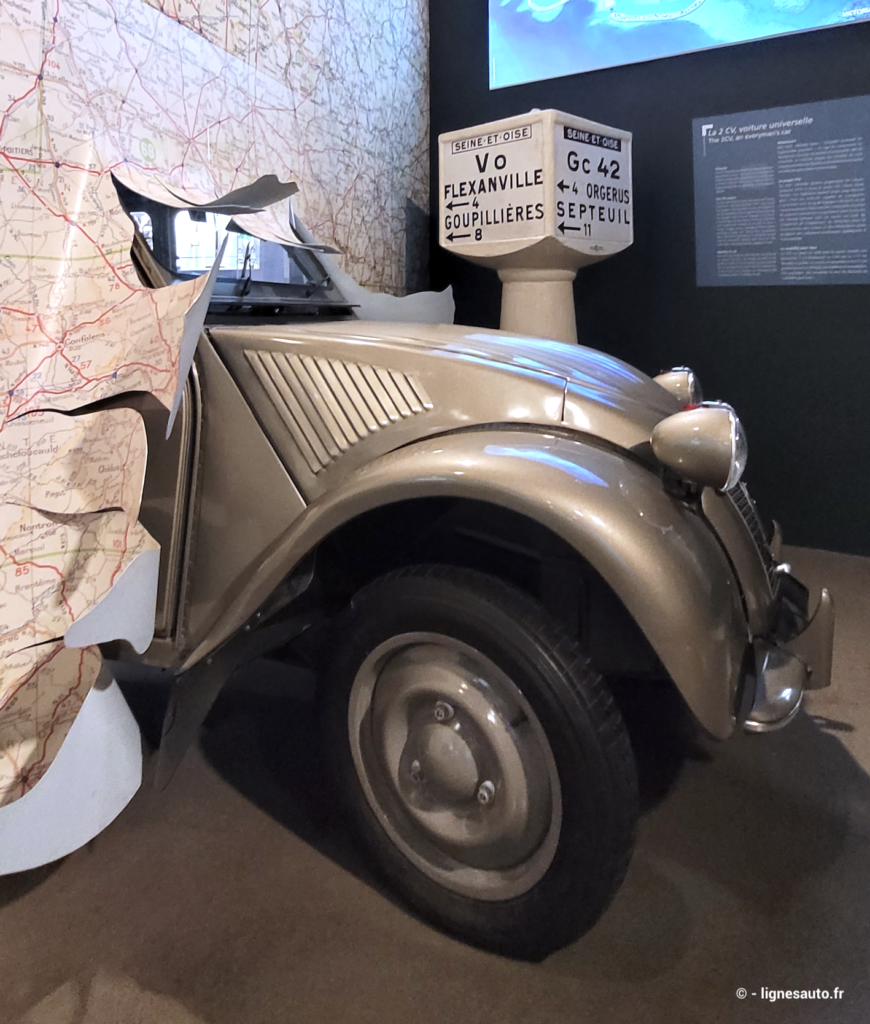

A Citroën 2CV sits in the middle of this area dedicated to Michelin maps and terminals. And with good reason: this model is a pure Michelin product, designed in the form of the TPV (Toute Petite Voiture) until 1939 – when it was due to be presented at the Paris Motor Show – and radically redesigned during the war before finally being unveiled in 1948. The concept of the minimalist 2CV originated in a survey launched by Michelin in 1922 on French motoring needs. The oldest of the 1939 series of TPVs was recovered from Michelin and can be seen in the Henri Malartre museum at La Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, north of Lyon.

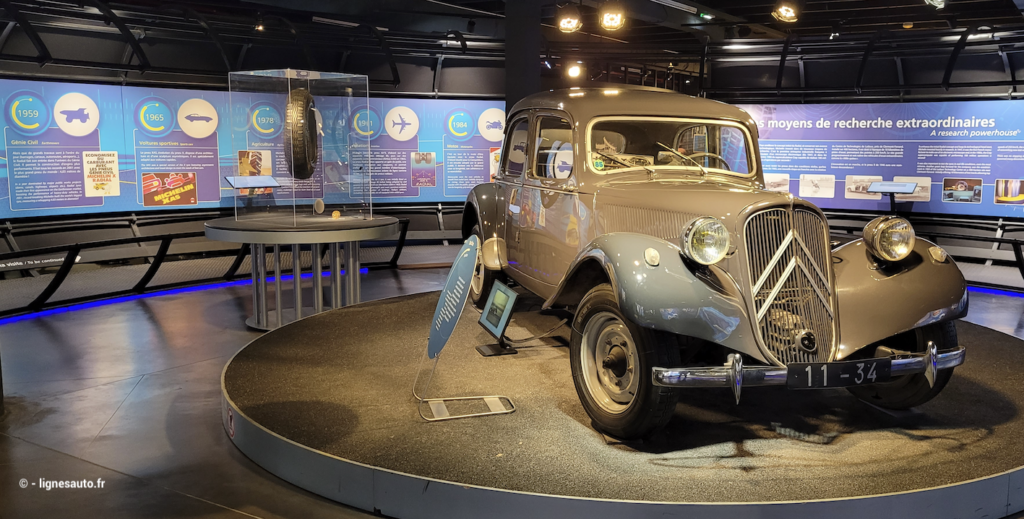

Another iconic vehicle in the exhibition, the Traction Citroën is presented in majesty in the exhibition (above) and remains a representative model in more ways than one. We’ll look at its many technological innovations (monocoque, reworking of the existing front-wheel-drive concept into a mass-produced model, etc.), but above all we’ll remember that it was this model that served as the transition between André Citroën’s era (it was presented in April 1934) and that of Michelin. This model benefited from a landmark tyre innovation, the ‘Pilote’ wheel below. Developed in 1937, the Pilote tyre had a tread wider than the height of the sidewall. The centre of gravity is lowered (for better grip and safety), while the whole unit is considerably lighter: the rim weighs just 1.5 kg! Thirty-four years later, Michelin remembered this when, a year after the SM went on sale, it offered ultra-light resin rims for this high-performance coupé.

This ‘Pilote’ innovation was followed less than ten years later by the radial tyre. The patent for the radial tyre was filed by Michelin on 4 June 1946. Technically, the tyre was designed with layers of material arranged diagonally (at 45° to each other), creating heat that was difficult to escape. With a radial positioning and sidewalls known as ‘flycages’, the new architecture gives the tyre less heat build-up, lower fuel consumption and improved comfort. This innovation flooded Europe, and François Michelin scored a master stroke by exporting it to the USA: Michelin became Ford’s official supplier for the Lincoln Continental Mark III in 1966!

The radial tyre remains without doubt THE most important revolution in the world of tyres, and cars were not the only ones to adopt it: HGVs (1952), aeroplanes (1981), in particular the Dassault Mirage III, motorbikes (1984) and even trams and underground trains, below, followed suit! Paris line 1 inaugurated the metro in 1951, before Montreal used it in 1966. From 1977, with the arrival of Renault in F1, radial tyre technology revolutionised competition. Ferrari joined Renault and between 1979 and 1984 Michelin won no less than 59 out of 112 GPs…

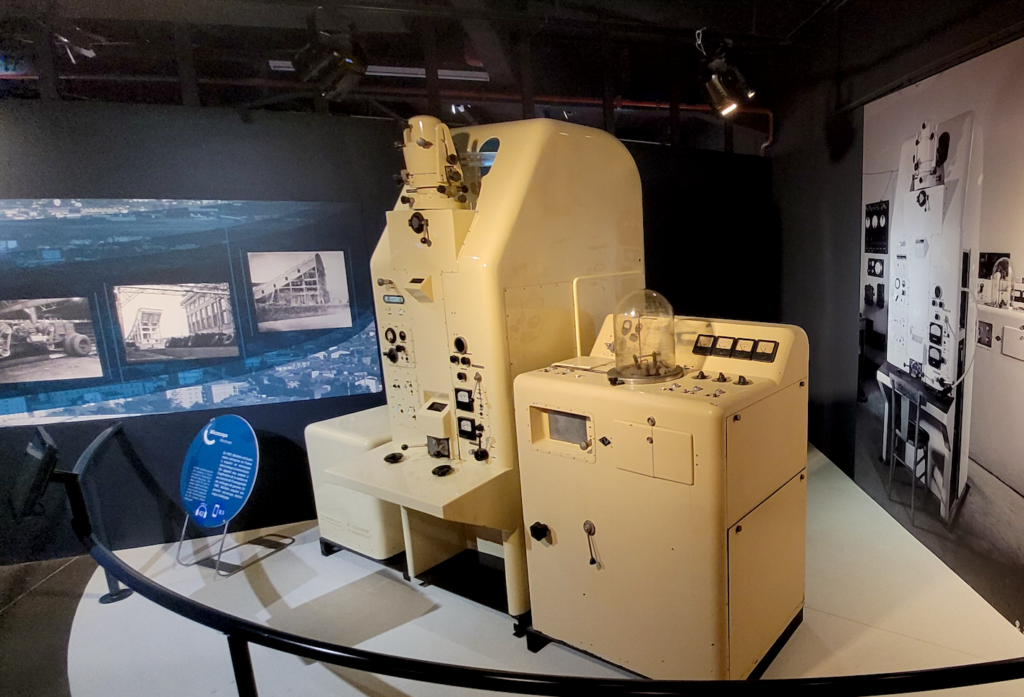

And to develop all these innovations, or better still, to create the unthinkable, Michelin has always used cutting-edge technology. Particularly in the manufacture of rubber compounds, which are so important in the composition of tyres. And one of these tools stands majestically on the tour route: the electron microscope (below). Just two years after the end of the Second World War, in 1947, Michelin became the first French company to adopt such equipment.

It was still only a Thomson-CSF prototype, but the engineer Jacques Bouteville used it with talent. It was devoted to exploring matter and checking the homogeneity of rubber mixtures. This first microscope was classified as a Historic Monument by the Ministry of Culture in 2014. In 1967, Michelin acquired its first scanning electron microscope…

And for all these innovations to make it through to production in compliance with draconian quality rules, more and more tests had to be carried out. In addition to the tracks at Cataroux until 2000 (see the post ‘l’Aventure Michelin-1’) and those at Ladoux, tests of truck tyres with radial architecture were carried out at high speeds with this strange DS (above) called ‘mille-patte’. This monster, the colour of Casimir, stands on ten wheels (not including the one being tested) and has two 350 bhp Chevrolet V8 engines. The machine weighed 9 tonnes and ran well into the 1980s.

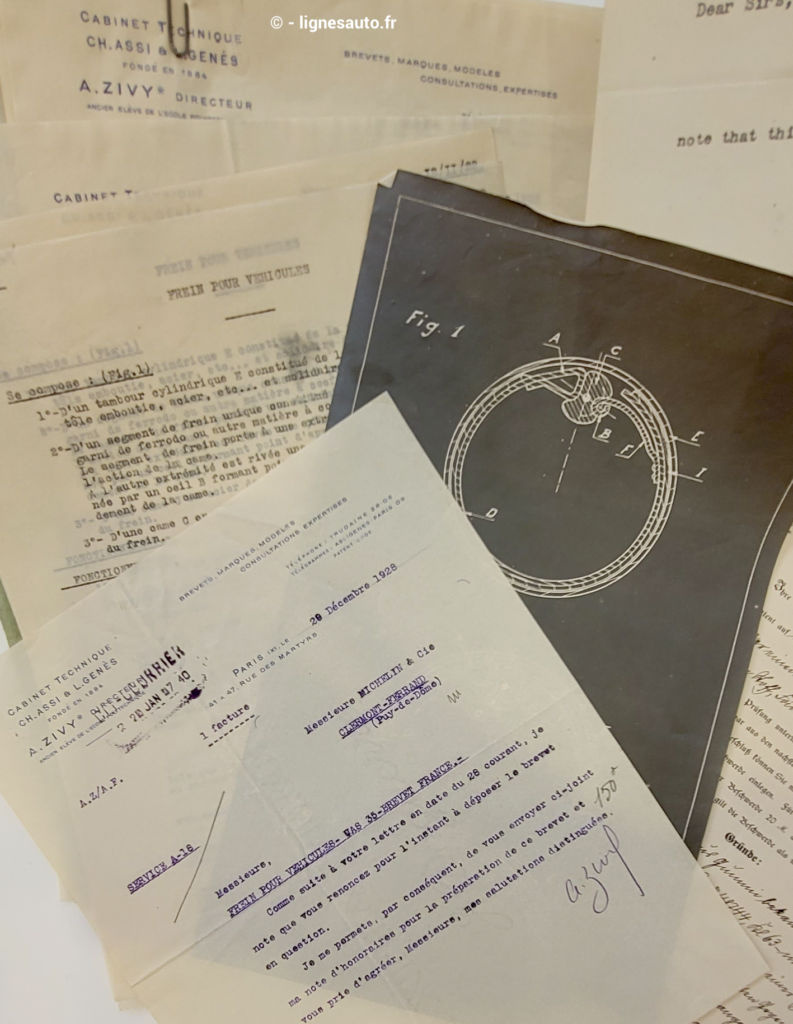

As you can imagine, all its innovations are patented (above). In 2018, Jacques Bauvir, then head of the group’s intellectual property department, explained to Les Echos that “from 120 patents at the turn of the 2000s, we now issue 400 a year“. And as in the days when Michelin owned Citroën, secrecy was the fundamental basis of research, whether technical or stylistic. Today, this image is changing, as Jacques Bauvir told Les Echos in 2018: “Secrecy is still part of our strategy, but the line between secrecy and patenting is increasingly moving towards the latter. We are pragmatic: we patent innovations that can be seen and keep secret what cannot be seen as long as it is possible to do so.”

Also according to Les Echos in 2018, at the time Michelin’s portfolio included no fewer than 12,000 patents worldwide protecting 3,400 inventions, as well as 4,900 designs and 17,600 trademarks. “In fact, the portfolio is valued by Brand Finance at 7.930 billion dollars,” wrote Erick Haehnsen, editor of Les Echos at the time.

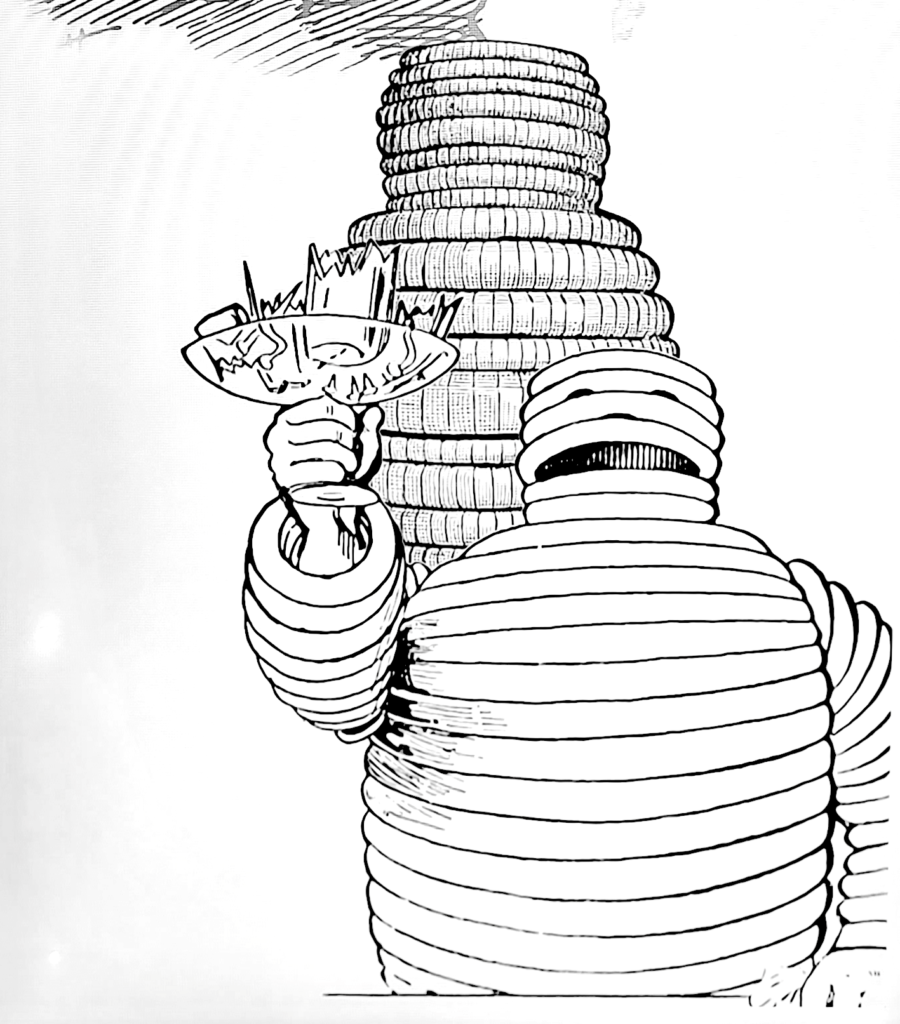

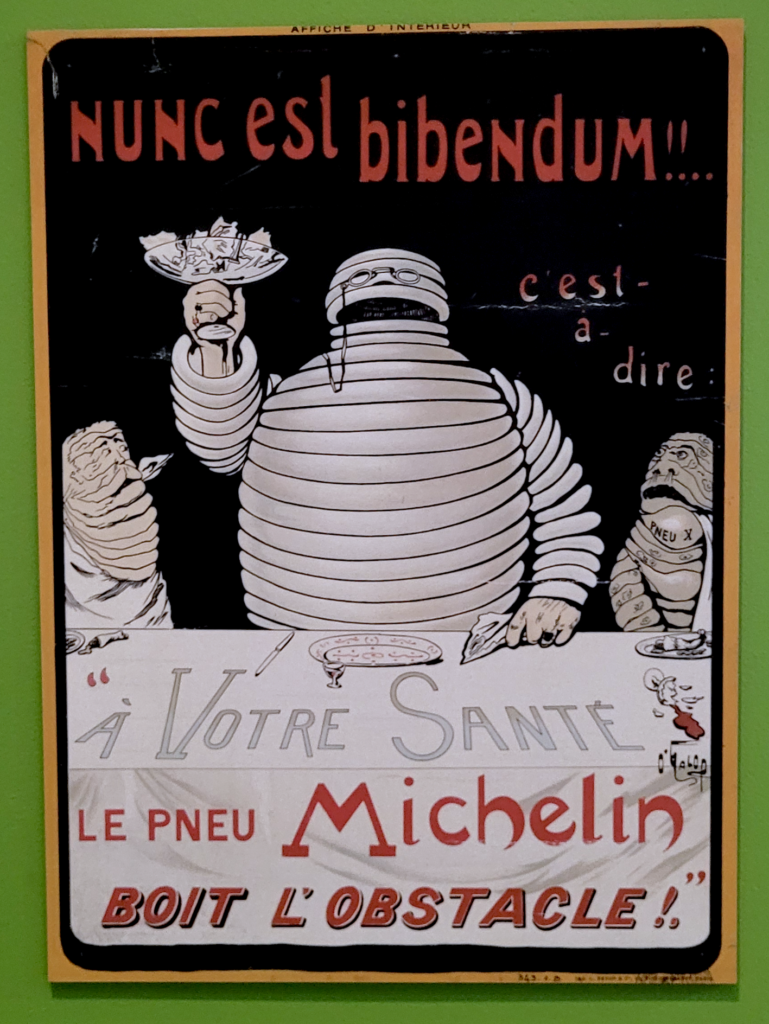

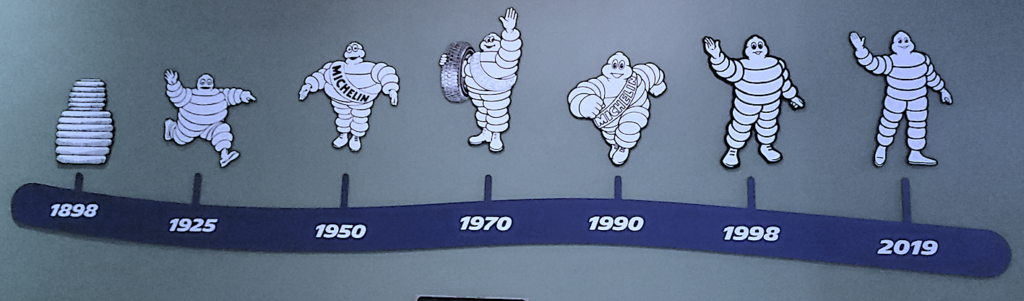

BIBENDUM

The Michelin Man was born from the intersection of two stories. The first is recounted in the Michelin Adventure book: “In 1893, André Michelin explained to an audience that the tyre was capable of absorbing the shocks of the road and used the formula “the tyre drinks the obstacle”. The second follows a few lines further down, when Édouard Michelin remarks in front of a pile of tyres “with arms and legs, it would make a man.“

In 1898, the cartoonist O’Galop met André Michelin and presented him with a drawing of a pot-bellied man brandishing a broken bock and exclaiming ‘Nuc est bibendum’, which means ‘now is the time to drink’. Bingo, the drawing hit the nail on the head and the bibendum by graphic designer O’Galop is perfectly in tune with “the tyre that drinks up the obstacle“. From this formula, we shall retain the name Bibendum for the Michelin emblem. And this has been the case since 1898…

AND TOMORROW?

The attraction of this ‘museum’ of the Michelin Adventure is that it opens the doors to the future. While the world of cars likes to unveil concept cars from time to time, which are the forerunners of the design and technologies of the future, the world of tyres is not to be outdone, with Michelin focusing on three main areas of research: the airless tyre, the connected tyre and the… lunar tyre!

Below, the UPTIS Airless tyre, which stands for tyre without air, solves the problem of punctures by eliminating the presence of air inside the structure. In its place? A vacuum and sipes that perform the function of the sidewall, while accommodating the tread and enhancing the tyre’s dynamic qualities at high speeds and when cornering. In short, the squaring of the circle that imposes a total breakthrough in terms of architecture and materials used. It was presented in 2019 and represents “the new generation of airless solutions and illustrates Michelin’s expertise in terms of high-tech materials.“

Below, the VISION tyre was presented in 2017. It is both a wheel and an airless tyre intertwined in the same coloured structure. It is bio-sourced, with a renewable tread that can be changed without affecting the rest of the wheel/tyre assembly. And above all, it’s connected. Patience, this intelligent tyre, beautiful and a complete break with the present, will not be available before the 1950s. But car designers are already incorporating it into some of their designs. Tyres could therefore follow the same evolution as car headlights: in the past, round headlights were considered warts, but today they are technological and integrated, an integral part of exterior design. Same future for tyres?

Below, the MiLAW tyre for a destination far, far away: the moon! “Michelin has been chosen by NASA as part of the Artemis project to equip future lunar vehicles.” The project proposes a revolutionary wheel, inspired by UPTIS technology, which is capable of withstanding the extreme conditions encountered on the lunar surface. As a reminder, the first lunar vehicle rolled onto the moon on 31 July 1971 with David Scott at the controls. The lunar vehicle fleet consists of three Lunar Rover Vehicles left behind by Apollo missions 15, 16 and 17. A 100% electric fleet…

Don’t hesitate to visit l’Aventure Michelin and wander the streets around the Cataroux factory and its huge test tracks. Please note that the museum is closed from 6 January to 3 February 2025. Outside this period, it is open from Tuesday to Sunday, from 10am to 6pm, and every day. From 6 July to 1 September, it is open every day from 10am to 7pm. Mark your calendars!