We left the Giugiaro-designed Renault 21 and Renault 19 to take off commercially in episode #01. We pick up the story with the launch of the X57 programme, which would give rise to the replacement for the Supercinq, launched in 1984: the Clio, shown below, which went on sale in 1990. Let’s take a look back at the context of the company, which underwent profound changes during the development of the Renault 19 and 21.

Renault first changed its CEO in January 1985, a year before the R21 arrived in dealerships. The departure of CEO Bernard Hanon (1932-2021), appointed in August 1981, followed a financial result that had plummeted into the abyss. But Hanon’s hands were tied by the government, which imposed savings without layoffs and without touching anything, or almost nothing.

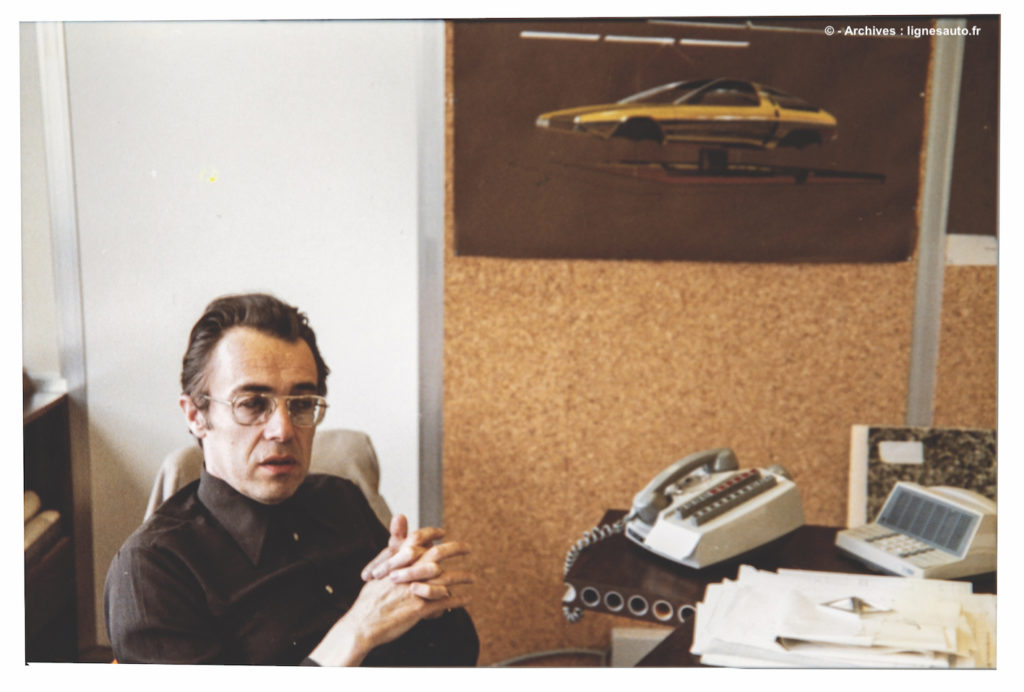

Georges Besse (1927-1986), who came from Pechiney, took over in early 1985 and cleaned house. This included pulling out of the United States with AMC, which led to Robert Opron leaving less than a year later, as he wanted to set up a satellite design studio across the Atlantic. Gaston Juchet returned as the brand’s style director. Ten months after taking the helm at Renault, Georges Besse saw the first models of the X57 project for the future Clio in November 1985.

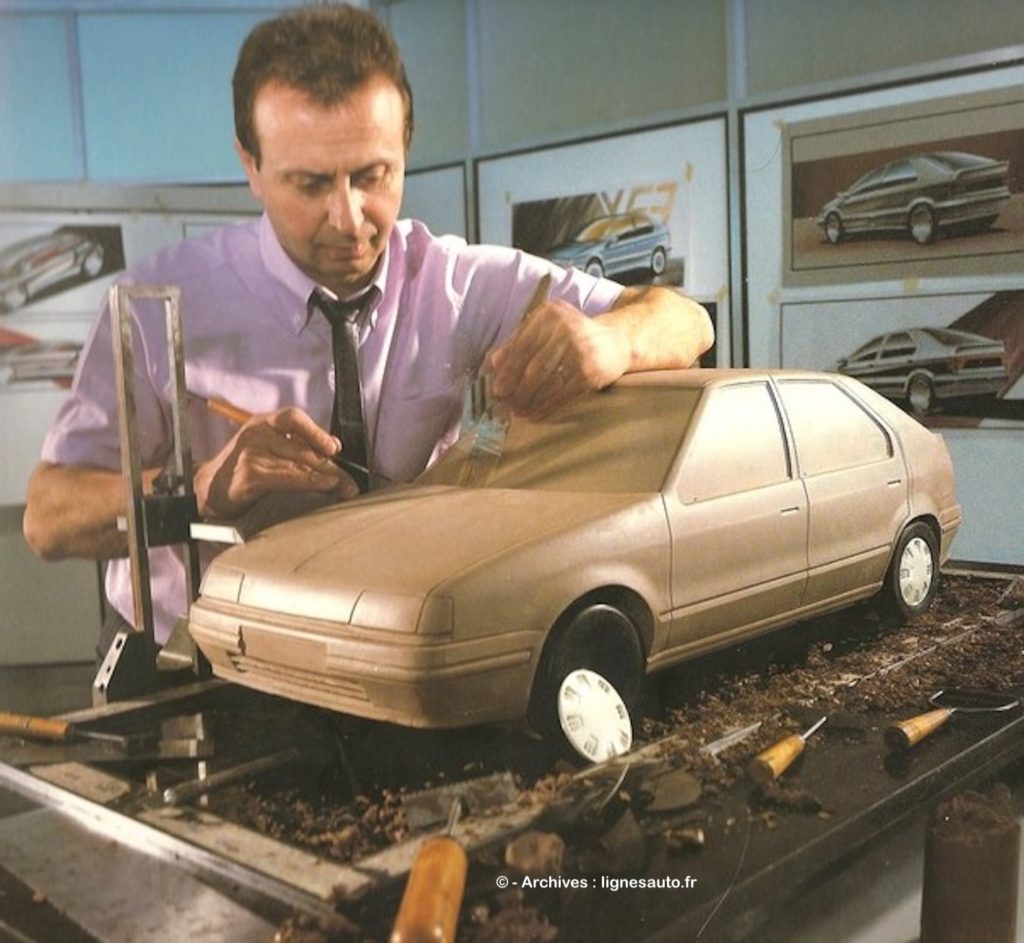

There were three of them, chosen from seven 1/5 scale proposals unveiled to the design team a month earlier. The Renault 21 was at the industrialisation stage and the Renault 19 (clay model below) was nearing final design based on Giugiaro’s model. Renault’s industrial designers encountered some difficulties in bringing it back into line with the specifications. The Clio X57 project pushed the product towards a perceived quality identical to that of the segment above, namely the Renault 19.

This was the first time that an heir to the R5 had such ambitions, and it was this that led to the name change. With Clio, Renault wanted to usher in a new era. This was essential, as the R5 and then the Supercinq had suffered from the arrival of the Peugeot 205 in 1983. However, Renault’s competition department knew that Jacques Calvet, the boss of PSA Peugeot-Citroën, was hesitating to renew the ‘sacred number’, preferring the 106-306 duo to do the job. This was a mistake. The Clio would live on for eight years before the Peugeot 206 arrived…

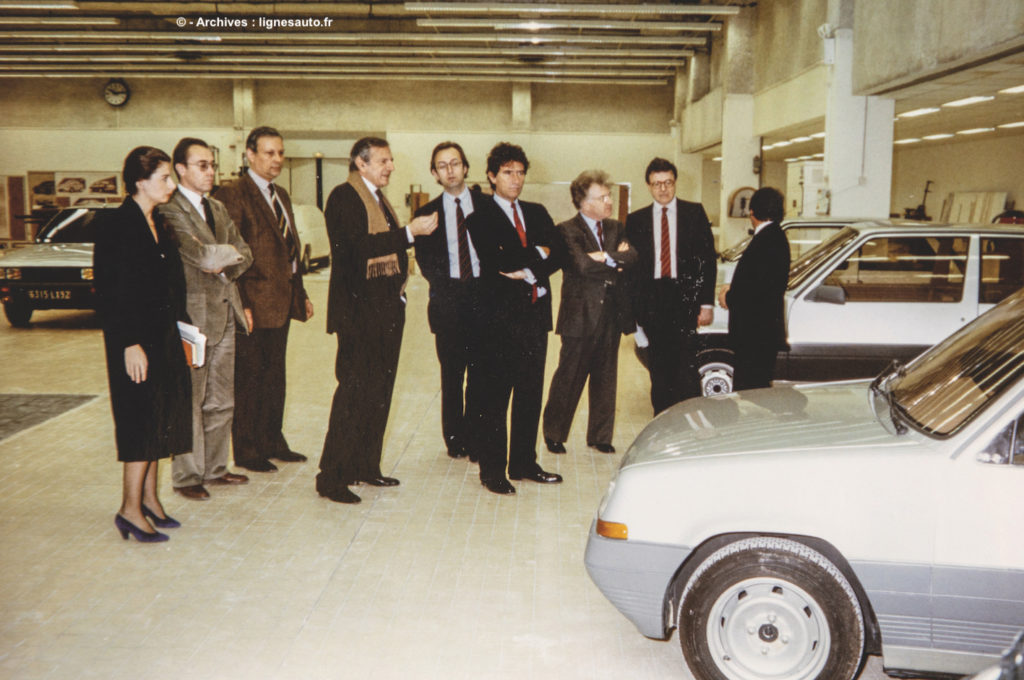

However, it was not all plain sailing at Renault, with Gaston Juchet preparing to hand over the reins to Patrick Le Quément. More than a year before this deadline, in April 1986, with the Renault 19 and Clio in the pipeline, a design seminar was held, marking a real awareness of the changes to come: CAD, computer-generated images (still known as “synthetic images”) and the transformation of the internal organisation of the design centres. The Nanterre and Rueil sites were finally merged at the end of the 1980s in Boulogne Billancourt (below) before plans were made to move to Guyancourt’s Technocentre, which opened in 1998, more than ten years after Gaston Juchet’s departure.

This 1986 seminar provided a detailed overview of how the various Renault studios were operating one year before the departure of the design director. The latter noted that ‘‘the total design workforce is 122 people spread across four centres.’’ The first, referenced as 0895, included management, administration, advanced design led by Nocher and special studies. The second, listed as 0896, was responsible for interior design, headed by Piero Stroppa. The third centre (0897) was dedicated to exterior design, with Michel Jardin as studio manager A in Rueil and Jean-François Venet (below) in Nanterre for studio B. Finally, the fourth centre was responsible for industrial vehicles and miscellaneous projects. It was headed by Jean-Paul Manceau.

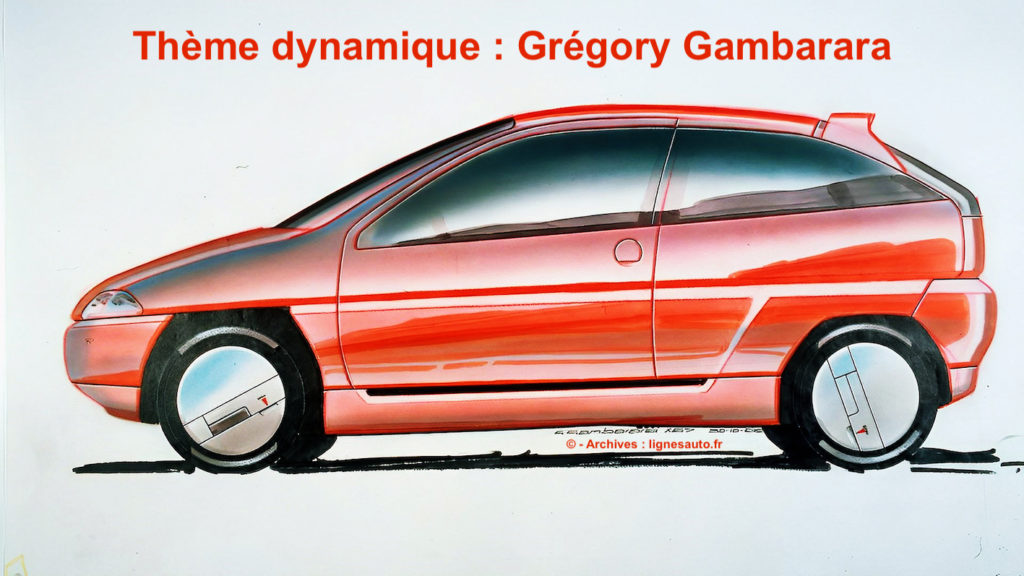

In 1986, Juchet revealed that ‘’we therefore have roughly the same potential between interior and exterior design. We have a total capacity of 132 positions, which means we have four vacancies in design and six in the model-making departments.’’ It was in this context that the X48 project for the future Renault 21, the X53 for the future Renault 19 and finally the future Clio X57 were born. Below is one of the style studies by Grégory Gambarara, who was working on the IRIS/X-05 project at the time: https://lignesauto.fr/?p=33834. In other words, the entire structure of the Renault range was affected.

And there is no shortage of work, as Gaston Juchet notes: “We currently (1986) have 15 major projects in the pipeline, including the styling for phase 2 of the R9/R11 and the R25. Added to this are the R21 bicorps, the US versions of the R19, the preliminary phase of the X54 (Safrane from 1992, below is a 1987 project), the F40 project (Renault Express), the 550 (unknown to us, no other notes on this NDA programme), the GTA (Alpine) and the Vesta 2.“

This avalanche of products, some of which are key to the range, is positive, but the flip side is less so, as Gaston Juchet points out: “It’s an advantage to have two design centres (Studio A and Studio B, NDA), but the disadvantage is that they are very far from the design office. In addition, the Rueil centre is very poorly laid out over four floors, with union disputes in the basement (health and safety issues in the model workshop) and the ground floor and first floor are completely full. It is very difficult for us to ensure confidentiality and work in peace.“

It was against this backdrop that Georges Besse discovered the first three models of the Clio five months before the seminar, in November 1985. Two of them had a very ‘utilitarian’ and vertical rear end. The third was more dynamic. As with the Renault 19, designed at around the same time, Michel Jardin noted that no advance work had been done to develop a technical architecture that would give designers more freedom. He wrote in the seminar report that ‘‘as no advanced studies had been carried out in previous years to prepare the design offices for a change in architecture, we cannot maximise the height/width ratio associated with the existing front and rear tracks.’’

In January 1986, the advanced style proposed architectural modifications that would give rise to four new models. Michel Jardin emphasised that “these four selected models were configured for testing. In early June 1986, two models were selected for the style freeze scheduled for January 1987. ” Among these models was a rival design from the collaboration with Giugiaro, shown above on the right, when Robert Opron was still with the company.

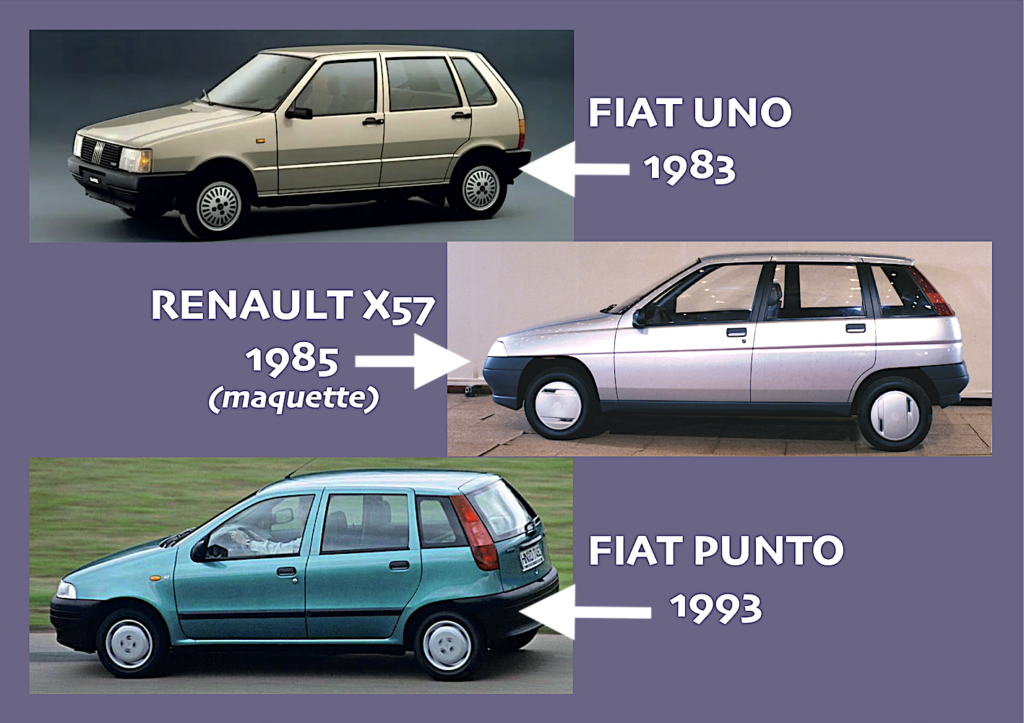

Unlike the R21 and R19 projects signed by the Italian master, the future Clio lacked appeal. Worse still, the Italian proposal was similar to the architectural theme of the Fiat Uno, which had been launched two years earlier in 1983. However, some people in the Product department seemed to like the Italian model and defended it right up to the final test! Giugiaro’s work for Renault coincided with the launch of the project for the future Fiat Punto in 1993, three years after the Clio (see the three cars above).

It must be said that although Renault ultimately did not choose the Italian’s proposal, the latter recycled it perfectly for Fiat! Let’s not throw stones at the Italian, as his colleagues at Pininfarina and Bertone have never been shy about recycling models rejected by one manufacturer and offering them to competitors. Take a look above at Bertone’s Alfa Romeo coupé, which was rejected by the manufacturer. Doesn’t it bear a striking resemblance to the XM coupé, a saloon car designed and approved by Bertone at the same time?

At the end of this post, in the bonus section entitled ‘X57: the genesis’, you will discover the various internal proposals that competed with Giugiaro’s, as well as the stylistic changes made to the Clio project between 1986 and 1987. Let’s stay behind the scenes for a moment to discuss the context. Between 1986 and 1987, when, as you will discover below, the Clio finally took its definitive shape, Renault lost its boss, Georges Besse, who was cowardly assassinated on 17 November 1986 by the Action Directe group.

Raymond Lévy (1927-2018) succeeded him in 1987 and remained president of Renault until 1992. Another significant change took place in the same year: Patrick Le Quément was appointed director of Renault Design Industriel when Gaston Juchet (1930-2007) retired. Patrick Le Quément’s arrival came at a time when the X57 project for the future Clio was still undergoing customer testing.

At the same time, Patrick le Quément brought the two models for the W60 project (which would become the Twingo) back to the design studios now based in Boulogne: Gandini’s model, which was quickly rejected, and Jean-Pierre Ploué’s model, the W60. Patrick Le Quément transformed it, giving it a completely different shape. That of a real car! And that’s when things got complicated internally, because the Twingo’s X06 project, which would arrive two years after the Clio, was stepping on the latter’s toes. That was the opinion of some people within the company who doubted the viability of two vehicles in a virtually identical segment.

Patrick le Quément, interviewed by us on Monday 14 July about this latest event, which could have shaken the Clio, explains: “Jean-Pierre Ploué’s W60 model was designed to be a car positioned below the X57. When I saw it, I found it very interesting because it was a monocoque. It was in line with Renault’s strategy, which had just unveiled the Espace, and with my vision of the product, since I was about to write the letter of intent to President Raymond Lévy in which I outlined what would become the Scénic concept in 1991 (above). On the other hand, I found the W60 a little fragile, bordering on what we thought of as a licence-free car.“

“It must be said that we had no point of reference because there was nothing comparable. It also had the problem common to many Renaults at the time, with wheel tracks that were not wide enough to fill the wheel arches. So I asked the head of architecture at the time, Mr Pierre Beuzit, to make the car more spacious, in particular by widening the wheel tracks. I should mention that I had just come from Volkswagen-Audi, where Ferdinand Piëch, the boss at the time with whom I used to visit motor shows, gently mocked French cars with their wheels tucked inside the wings!“

“When I asked Pierre Beuzit to widen the tracks, he replied that if we did that, we would be wider than the X57 (Clio) project currently being approved. I simply replied that just because we had made a mistake with the Clio didn’t mean we had to start again with the W60! Fortunately, in the field of architecture, which is usually rather rigid, there was Patrick Pelata working with Yves Dubreil on the Twingo project.“

Concerns that the Twingo would be almost wider than the Clio did not last long. ‘’I went to see the chairman, Raymond Lévy, who was a rational man with no experience in the automotive industry,’’ explains Patrick Le Quément. “For him, my recommendations regarding the widening of the tracks and the car were obvious, so there wasn’t really any battle. And in the wake of this, after understanding how much our studio teams had been hurt by the choice of Giugiaro’s design for the R19 (see episode #01), I decided to end our collaboration with external consultants. I wanted to do away with this heavy feeling that our teams were only considered second-rate!”

The 1990 Clio thus brought an end to the series of Renaults designed by Giugiaro. Patrick Le Quément deserves credit for not disrupting the organisational structure put in place by Gaston Juchet. On the contrary, he retained the main designers, such as Jean-François Venet, Jean-Paul Manceau and Michel Jardin, as well as a few designers who went on to climb the ladder elsewhere, such as Jean-Pierre Ploué and Thierry Métroz.

But while Gaston Juchet’s DNA remained present within the walls of Renault, which became Renault Design Industriel with the start of the Le Quément era, the team grew considerably. It expanded from 122 people in 1986 to 309 at the start of the 2000s. One of the main reasons for this was the complete cessation of external collaborations, notably with Marcello Gandini and Giorgetto Giugiaro. Competitor Peugeot did the same with its collaboration with Pininfarina, and Citroën dropped Bertone at the same time. It was the end of an era…

Bonus: X57, the genesis of the Clio in pictures

In addition to Giugiaro, Renault’s two in-house studios (A and B) worked on the Clio’s X57 programme. It was Hermidas Atabeki, then an intern at Renault’s design department, who drew the initial sketch. Let’s take a look at how the styling of this first generation, launched just 35 years ago, has evolved. The sixth generation of the Clio is set to be unveiled before the end of this year…

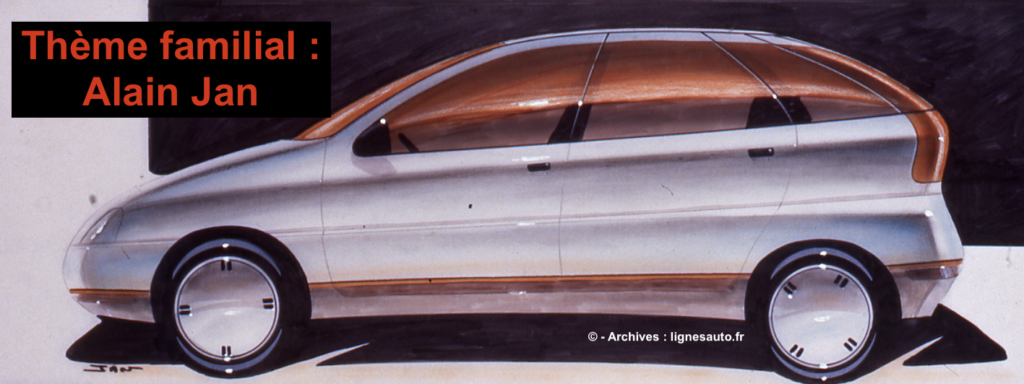

The style theme was chosen in 1986. After selecting from a number of 1/5 scale models, the style was narrowed down to two variants proposed by Studio A, led by Michel Jardin, and Studio B, managed by Jean-François Venet. Two models were developed independently, including the one above by designer Alain Jan from Studio A. Jan was working with designers Hemmi, Mignon, Milenovich and Mornard at the time.

The second internal model in the Renault style therefore came from Studio B, based on a sketch by designer Hermidas Atabeki. Upon seeing it, it is clear that this is the model that would become the final version. Placed in context, it clearly displays, like its internal rival from Studio A, an impression of solidity and quality that was light years ahead of the frail Supercinq, which had been launched two years earlier in 1984.

Viewed from the side, the model of Studio B in its three-door version (actually the right side of the model, with the left side representing the five-door version) is still far from its final design. This is particularly true of the rear, which is too thin with its large side window. However, a bulge in the rear wing shoulder attempts to add a little perceived solidity…

Four months after the 1986 mock-ups, the future Clio had not yet found its definitive style. In 1987, the two models from studios A and B were still competing internally. Giugiaro’s model, which can be seen below, was also in the running. Alain Jan’s model here retains the discreet shoulder of the rear wing, and the curve of the tailgate is beginning to take on the shape that would ultimately be chosen. The lights are horizontal and fairly wide.

Faced with its internal rival from Studio A, Studio B’s model evolved towards the style that would ultimately be chosen. The rear section has been completely redesigned and now features a tail light design similar to that of the production model. The curves of the tailgate are also similar to those of the series, while the rear window on the three-door version leaves a generous panel of sheet metal. This confirms the solidity required by the specifications.

Above, the same model of Studio B seen from the front three-quarter view also reveals a new front end similar to the production Clio. At the same time, the studios were strengthened by the successive arrivals of Thierry Metroz and Jean-Pierre Ploué. These two new designers worked on the X06 project for the 1992 Twingo, as well as on the 1993 Laguna saloon. Below, Thierry Métroz’s final model for the Laguna, dated 1988 and produced by Studio A.

Despite the reinforcement of studios A and B, which now have the same number of designers (as requested by Gaston Juchet), Giugiaro is still in the lead for his X57 project for the future Clio. As we saw above, his proposal below, supported by some internally, does not seem to sufficiently respect the specifications and the sacrosanct desire for quality that is apparent at first glance. While the front end seems to correspond to the various themes retained in the internal proposals, the three-side window concept, although offering great brightness, contributes to the feeling of fragility compared to the almost monolithic bodywork of the designs from studios A and B…

Below, the final comparison between the Renault model that was ultimately chosen (the one from Studio B, led by Jean-François Venet) and Giugiaro’s 1987 design shows the in-house studio coming out on top. This was a welcome turnaround at a time when Patrick Le Quément was taking the reins of the design department, which was then renamed ‘Design’. Above all, it marked the end of the adventure between Renault and Giugiaro.

1987 – STYLE FREEZE

Here is the style gel model of the Renault Clio, dated 1987. It has two different sides, showing above the 5-door version that would appear in June 1990, and below the 3-door version that would appear in September 1990. The slight shoulder of the rear wing has been retained, while the lights have taken their final shape. The bonnet is autoclave-moulded. The Clio no longer has much in common with the Supercinq, which was based on the 1972 R5. This time, it’s serious business with a striking advertising slogan: ‘Renault Clio, elle en met plein la vie.’ It would certainly impress the ageing Peugeot 205 and become the best-selling car in France from 1991 to 1997.

To further differentiate it from the Supercinq, Renault decided not to use a number in the name of this mass-market model. Before the arrival of the second generation Clio in early 1998, the first generation Clio sold just over four million units. Without the ‘prestigious’ Italian signature…

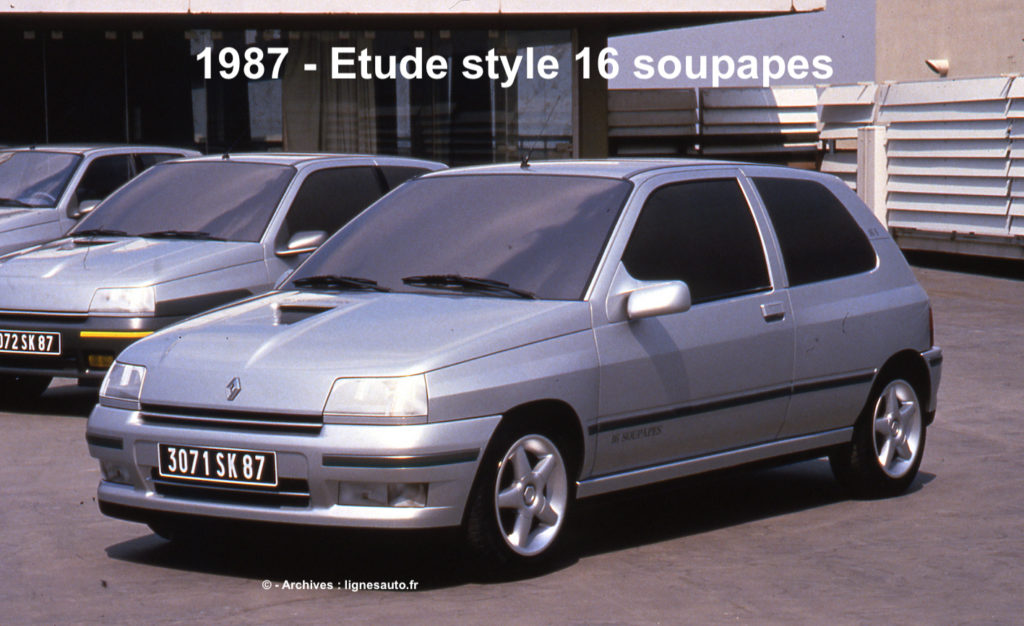

Renault made a huge mistake in the mid-1970s by not supporting the R14, which was stuck in a very limited range. This mistake would not be repeated with the Clio, which, like the R5 before it, would be available in multiple versions, including sports models. The 16-valve model shown above in 1987 was launched in 1991 with wider wings, an air intake on the bonnet and an engine borrowed from the R19 16S. It wasn’t quite the end of the turbo at Renault, but it was close! However, the Clio 16S was criticised for having poorer acceleration than the R5 GT Turbo it replaced.

Above is the very latest prototype approved during a test in 1988. As mentioned above, the Clio was competing alongside a certain… The Clio was then practically on track for industrialisation, which would still take more than two years. This was the time needed to manufacture the test prototypes, because although digital technology was already available, it did not yet have the power it has today to replace physical testing.

Before its launch in 1990 and the revelation of its new name, ‘Clio,’ the X57 programme underwent a whole range of endurance and reliability tests. This gave the french magazine l’auto-journal the opportunity to reveal the first images of this Renault, which would go on to become a big hit! Now it’s time for the 1992 Twingo, below, and the 1993 Laguna sedan…

The author would like to thank Patrick le Quément, Jean-Michel Juchet, Jean-Marie Souquet, Jean-Pierre Ploué, Thierry Métroz, and Grégory Gambarara. This article was written using interviews and personal notes from Robert Opron and Gaston Juchet, whom I met some time ago for interviews that now enable me to tell the story without distorting it too much!