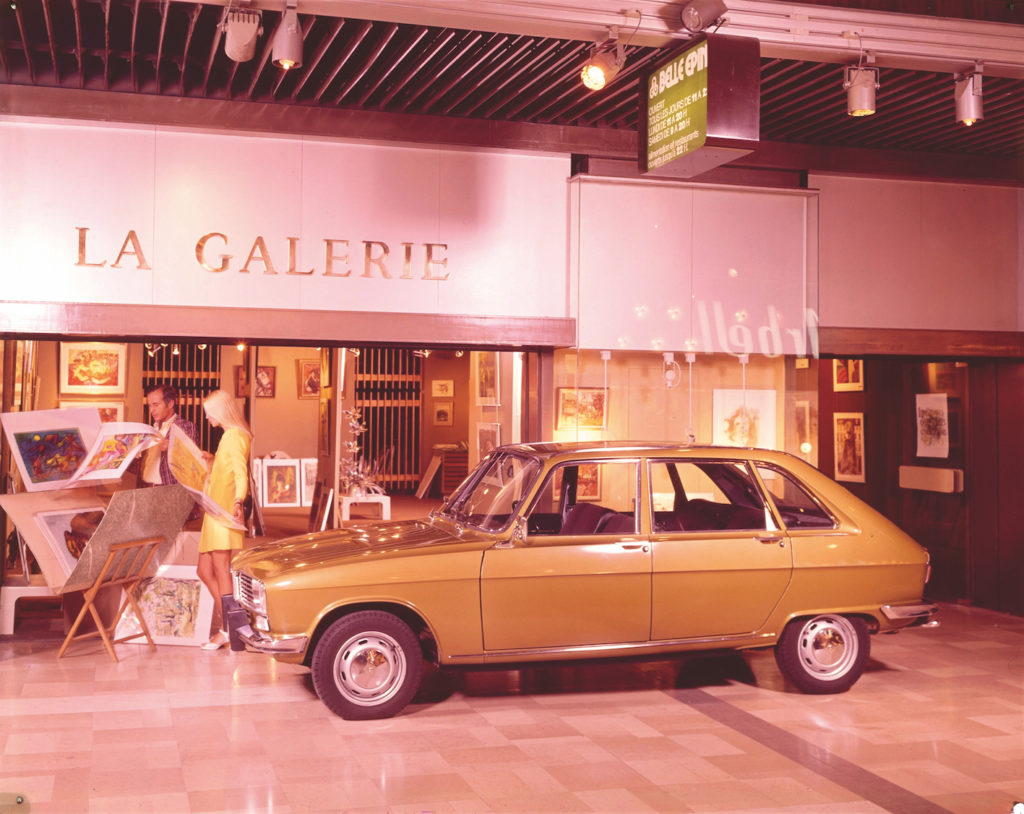

Marketed in 1965, the Renault 16, according to Gaston Juchet’s notes, “ was approached in an original way, by setting up a very compact multidisciplinary unit: the design office, bodywork and upholstery, sheet-metal working methods and styling. This unit was managed by Claude Prost Dame, the head of bodywork design. A strong commitment to innovation was evident: an unusually large one-piece body side panel, a new stretcher assembly that raised the roof laterally to improve access to the car, a panel heater and windshield base structure to form the dashboard, a longitudinally movable rear bench seat to modulate the rear passenger compartment, a luggage compartment and a fifth door. In addition, design and development time was particularly short. The result is a style that proclaims its functionality, much debated at the time of its launch, but which set the global trend for the five-door hatchback concept.

This first major project led by Gaston Juchet’s team was also, as his son Jean-Michel recalls, “a perfect alignment of the planets with the 115 project, which replaced the 114 (a rather outdated classic 4-door sedan). Yves Georges, Claude Prost Dame and my father were all of the same generation and young fathers. When Renault stopped the 114 project, Pierre Dreyfus asked them to start from scratch!“ This small team found itself in the rather comical situation of having to make the leap from an extremely mundane project (the 114) to an extremely ambitious and somewhat risky program.

“Dreyfus wanted a 1500 cm3 all-purpose car,” recalls Jean-Michel Juchet. “The kind we need. A modern car, for weekdays as well as weekends and vacations.” Pierre Dreyfus relied more on intuition than anything else, since it’s worth remembering that in the late 1950s, the product marketing department simply didn’t exist!

Yves Dubreil (former Twingo product manager) wrote for Renault Histoire that “Dreyfus’s starting point was Renault’s late entry into a segment already occupied by Peugeot, Ford and Opel, with classic three-box sedans, accompanied by large estate cars. The analysis showed that there was a rather young potential clientele looking for a multi-purpose car adapted to the new uses of leisure, second homes, family travel or transporting various objects, and that this clientele didn’t want to give up the elegance and comfort of a sedan.”

The energy of the team of thirty-somethings at the helm of the specifications brought a breath of fresh air. With one collateral victim: Philippe Charbonneaux (1917-1998), who felt totally out of the picture. He had worked for Renault on the R8 program, where he put his signature in the shape of a ‘C’ on the rear wing. For the rest, he tried to use his media connections to appropriate the Renault 16 design, even though all the drawings in the Renault archives make no mention of his presence on this 115 project.

In the June 2000 issue of the monthly magazine Rétroviseur, Gaston Juchet reflects tactfully on this designer: “I had designed the R16, in the form you know, when one day Charbonneaux came to visit us. Looking at what we’d done, he explained that the side reminded him of the stylized P on his stationery. And from that moment on, he thought he could let it be said that he had designed the side of the Renault 16.” But as ever, Gaston Juchet adds that Philippe Charbonneaux “was a charming man, who drew very well indeed.” Jean-Michel Juchet explains today that “it was a time when it was all about ego. On the one hand, there was Charbonneaux, the designer-consultant, recognized and experienced, and on the other my father, a young Renault employee. The styling department was unstructured and sometimes had a complex relationship with the body design department.“

That all changed when Fernand Picard handed over the director’s post to Yves Georges. “It was Yves Georges whom my father went to see with his drawing-boards when he was an engineer, and it was the same Yves Georges who gave him his blessing.“ In 1963, Charbonneaux was no longer consulted by Renault. Jean-Michel remembers that “from then on, he never stopped saying that the Renault 16 was his. But this Charbonneaux affair really touched and upset our father, because he was bound by confidentiality and couldn’t dwell on the subject in the media, which wasn’t in his character anyway.”

If the drawings of the Renault 16 signed by Gaston Juchet and dated 1961 are irrefutable proof of the concept’s origins, it’s clear that no single man is the father of this revolutionary sedan, as the designer himself agrees in his notes, referring to a certain Luc Louis. It was this talented modeler who enabled Juchet’s studies to take shape on a scale of 1/5 and even 1/1 in some cases. Luc Louis would steer certain details, such as the U-shaped rear bumper (above), in different directions from those chosen by Gaston Juchet.

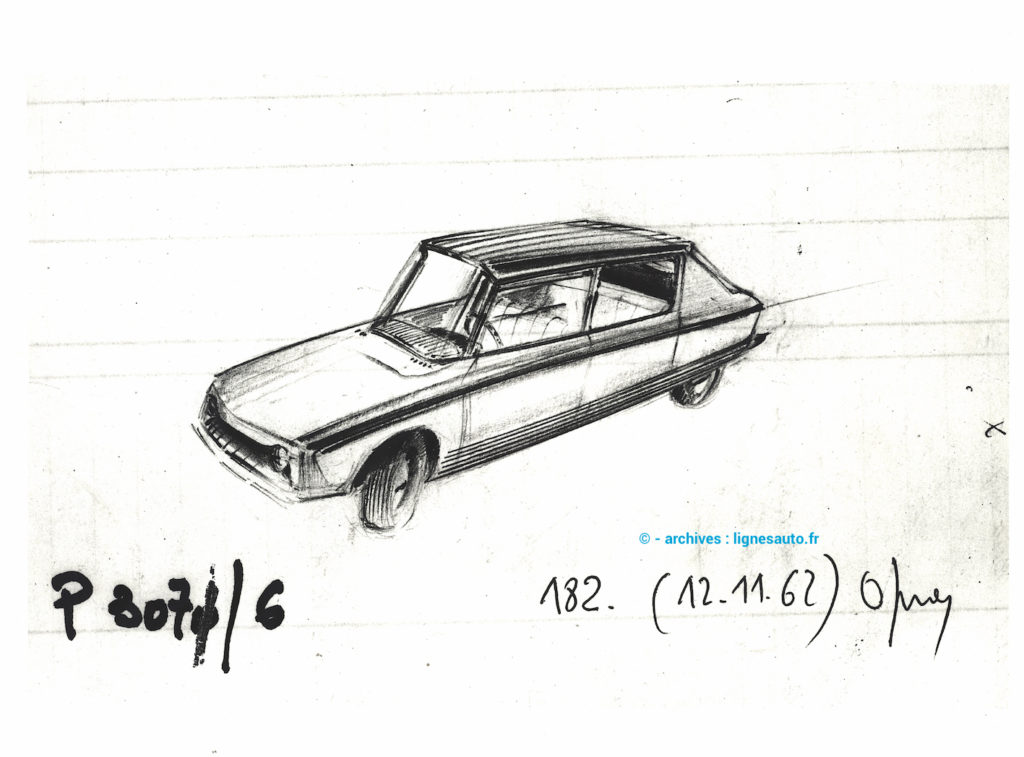

Luc Louis modifies the structure of the stern to install vertical lights as an extension of his original bumper. It’s worth taking a moment to get to know this discreet man. Luc Louis worked in the Simca styling office in the 1950s, with a certain… Robert Opron. When the Simca studio dried up, Opron went to Citroën (below, a sketch of this designer) and Louis to Renault. Not surprisingly, the idea of a five-door sedan was in the air at Simca and other manufacturers.

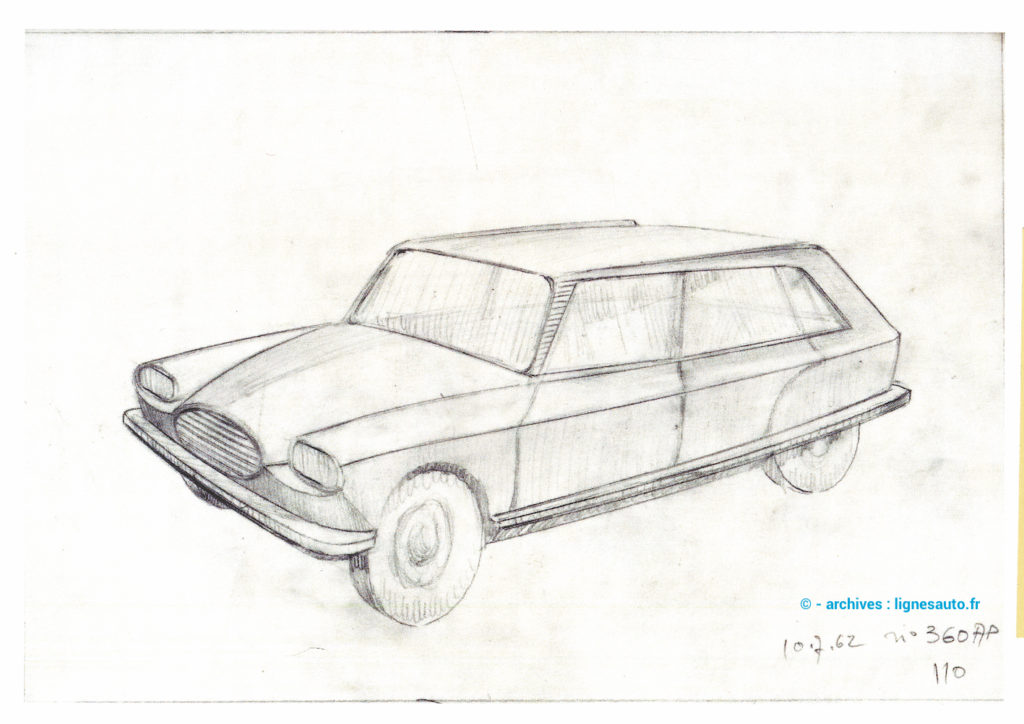

And with it, the famous flank-pavilion junction developed concomitantly by Renault and Citroën (project 115 at Renault and project F at Citroën), without either being aware of it. But clearly, the 1961 drawings signed Gaston Juchet put an end to any idea of copying on either side. Especially when you consider that Robert Opron didn’t join Citroën until 1962, when he began work on the AP (and later F) project above. In the same year, 1962, Gaston Juchet was already designing the “welded roof/side panel” architecture for the future R16, as shown below.

Gaston Juchet’s innovations were not lacking on this 115 project: work on the front end, studies on opening systems and interior styling too, notably with a novel ventilation system with a flat diffuser running across the entire width of the dashboard. After four years of design and industrialization work at the brand-new Sandouville plant, located on the Billancourt-Flins-Le Havre axis (below), 600 examples of the Renault 16 were delivered to dealers.

Both the press and potential customers were enthusiastic. Quality was praised – the R8 Major had shown the way – functionality was surprising, while the styling, sometimes criticized as innovative, didn’t prevent the Renault 16 from embarking on a career that lasted fifteen years, until it disappeared from the market in 1980, five years after the launch of its successor, the flagship Renault 30. The R16 was voted Car of the Year in 1966, beating out the… Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow and the Oldsmobile Toronado.

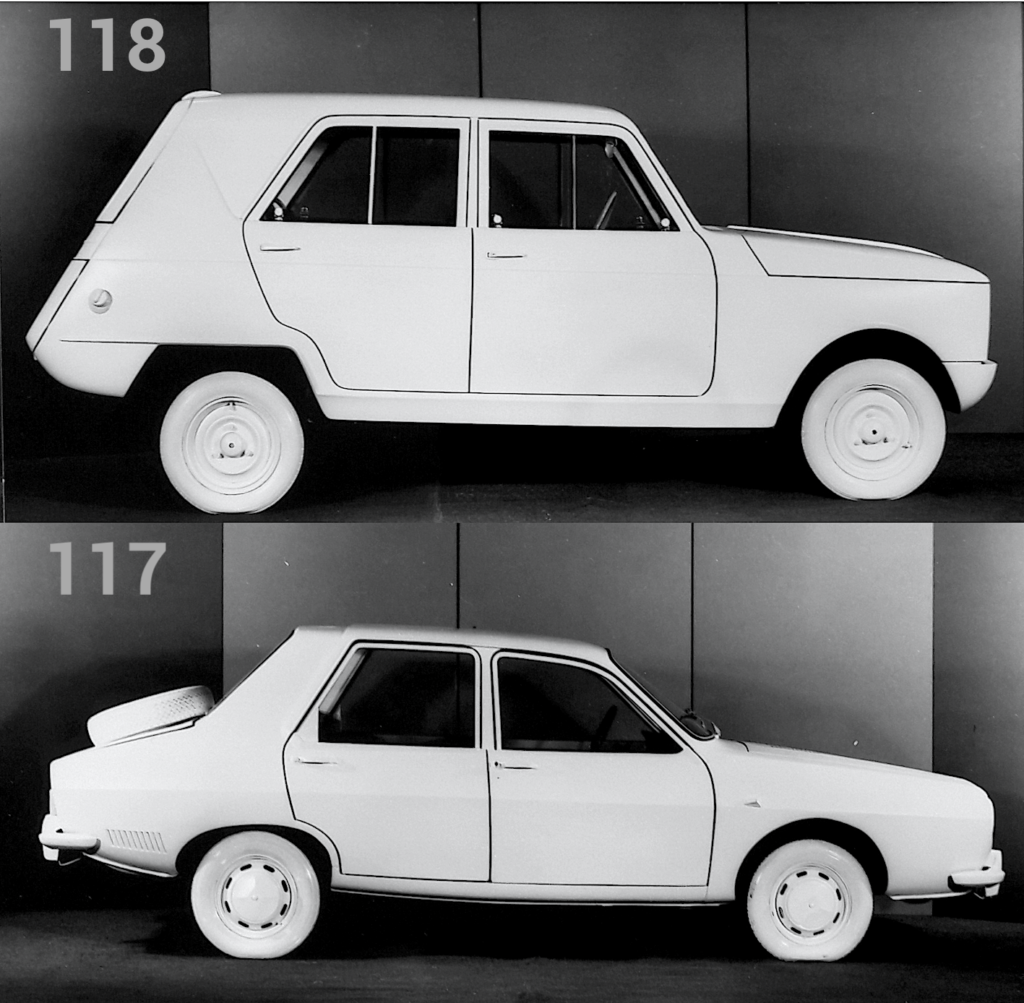

Journalist Édouard Seidler wrote in “Le Roman de Renault” (Éditions Edita) that “it was with the R4 and then the 16 that the Régie really came into its own. With the introduction of the R10 Major the same year, the Régie’s range now extends from the 4 to the 16, including the Dauphine, various versions of the 8, the 10 and the Caravelle. There’s no shortage of ammunition in Renault’s arsenal, where prototypes of projects 118 (future R6) and 117 (future R12) are already in the works.” See below.

BONUS LIGNES/auto: Citroën’s Project F killed off by the R16?

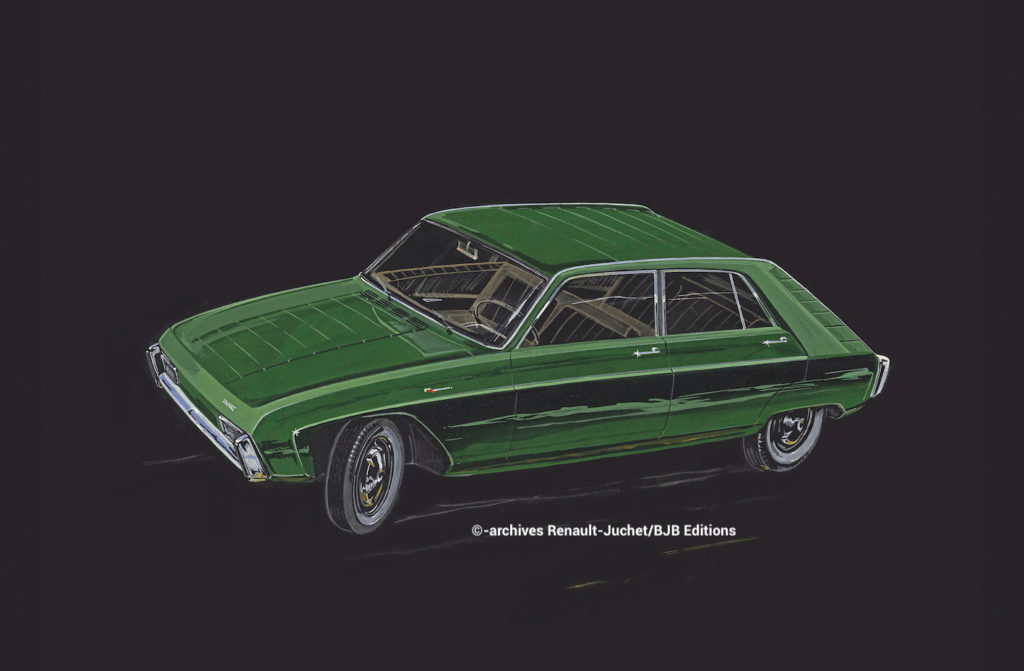

The Citroën F project above is a compact 5-door, 4-cylinder flat or Wankel rotary piston, metal or hydraulic suspension, depending on version. The two sedans (Renault 16 and Citroën F), which are not the same size, feature a sloping rear end with a fifth door. The other thing they have in common is an industrial system that pinches the body sides together with the roof to weld them together. The result is two backbones, hidden by a metal bead on the Renault and better integrated on the Citroën.

This technique eliminates the need for gutters, giving better access to the rear seats and improved headroom. Citroën choked in 1965 when it saw the R16 in the press, because the entire structure of its Project F was based on this welding principle! But Renault had patented the system, not Citroën! It was therefore impossible for the latter to use it without paying substantial royalties to the Régie. Citroën’s boss, Pierre Bercot, obviously refused!

Was it this legal problem that brought the F project to a halt in 1967, two years after the R16 went on sale? “The F project was halted even though all the tooling had been ordered and some was already in place at the Rennes-la-Janais plant,” Robert Opron told us in the 1990s. He added that “when we discovered the Renault 16, we were shocked, even if I didn’t find it very aesthetic. But I still found it interesting. As for the idea of the roof with the welded seam, it was an idea of Prost-Dame at Renault. He and Flaminio Bertoni at Citroën had the same idea, jointly. It happens all the time. Does this mean there were leaks from Citroën to Renault? You can always romanticize…”

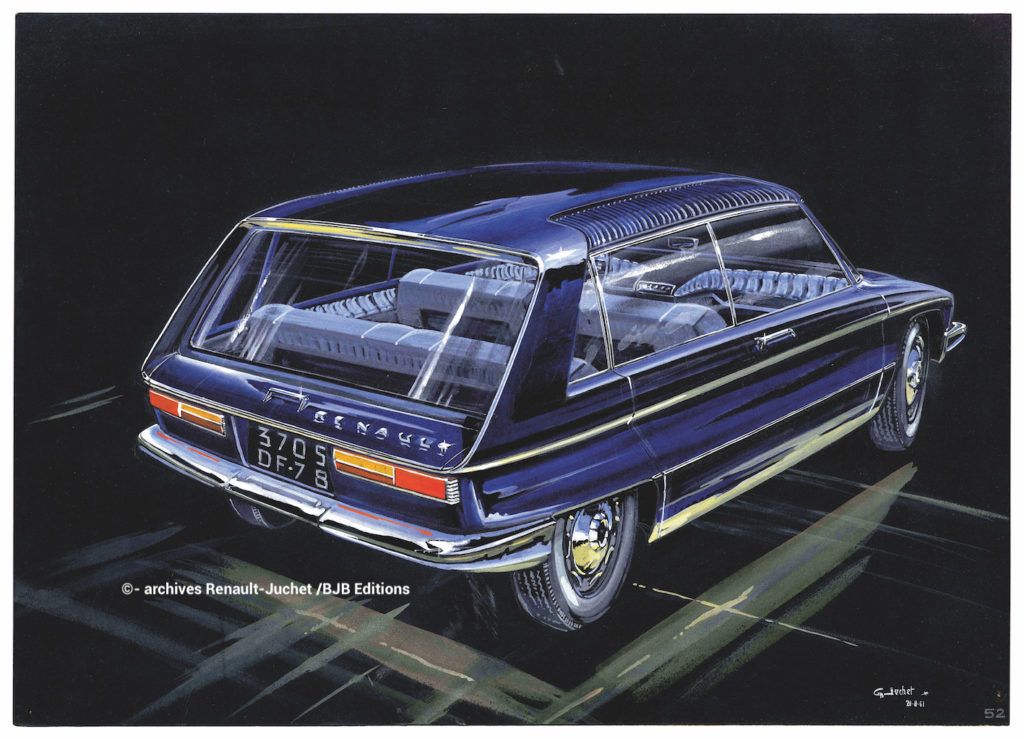

BONUS LIGNES/auto: the Renault 16 convertible and station wagon

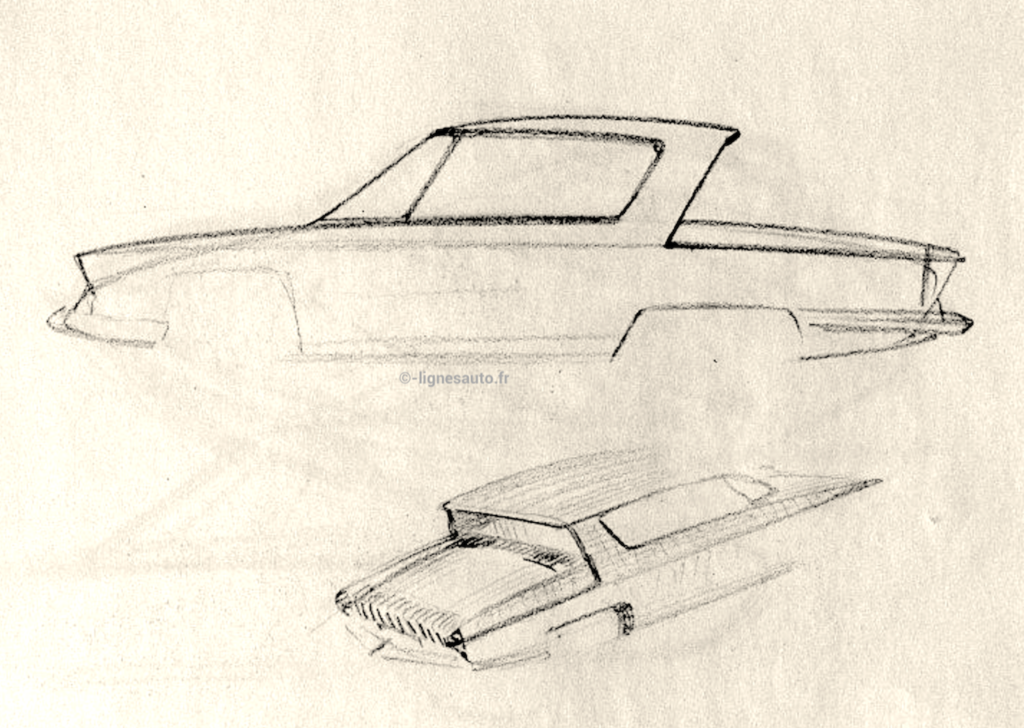

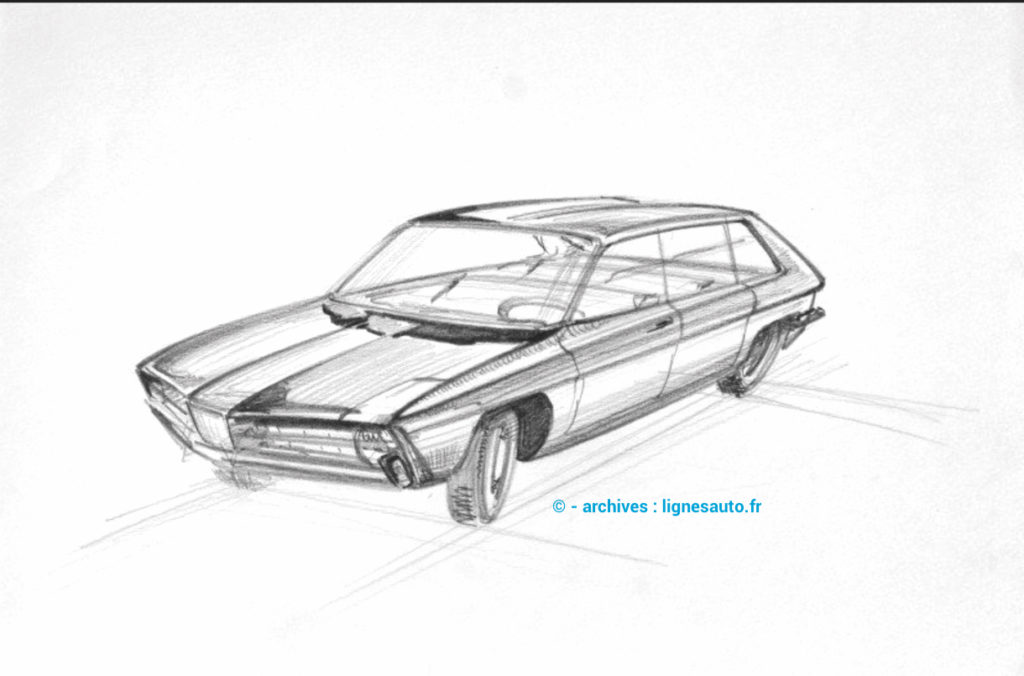

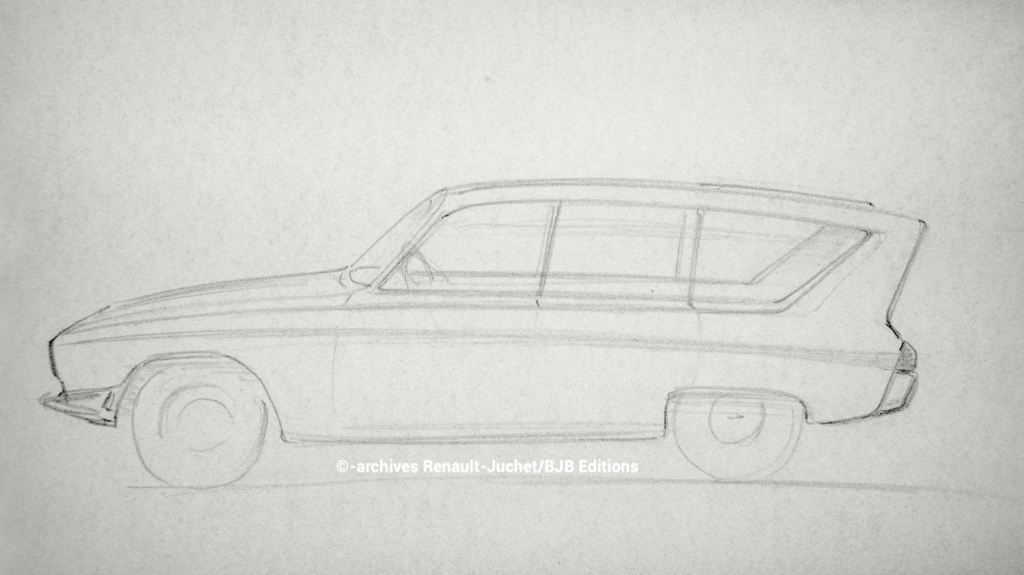

The station wagon silhouette based on the Renault 16 has not undergone extensive gestation. The 115 program mentioned it, but Renault was more interested in the coupé-cabriolet version. Nevertheless, Gaston Juchet proposed several sketches of this Renault 16 station wagon. Above, this proposal is very typical, with a characteristic ‘Z’ line, very Citroën Ami 6. The sketch below, more classical with the rear doors of the sedan, features vertical lights to better clear the loading entrance.

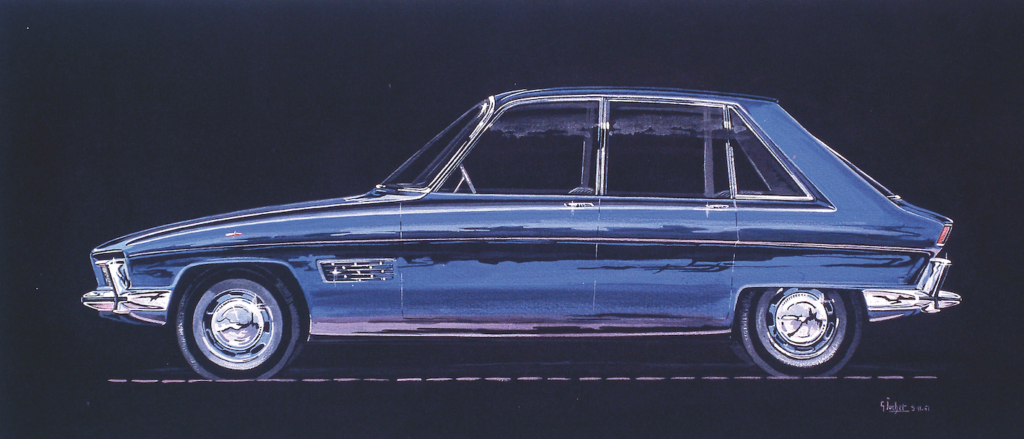

As early as April 1962, a year after the broad lines of the sedan had been defined, Gaston Juchet began thinking about a convertible version of the 115 project. On the paintwork, the stylist proposed four headlamps on the grille, foreshadowing those of the TX sedan. The latter will feature square headlamps, rather than the rectangular ones that Gaston Juchet wanted. This convertible project was soon transformed into a coupé, thanks to the study of a rigid hard-top in 1963 below.

This version initially appealed to management, who pushed the project through to the 1/1 scale model and prototype stage. Gaston Juchet’s drawings show a coupé with a long, rather horizontal trunk. His paintings reveal a cabin with two comfortable bench seats. Unfortunately, the Renault 16 coupé cabriolet did not compete with the Peugeot 404 coupé. It’s true that the Renault range relied on its Florida and Caravelle models, already present in the line-up.

BONUS LIGNES/auto: Gaston Juchet and the “Z” line

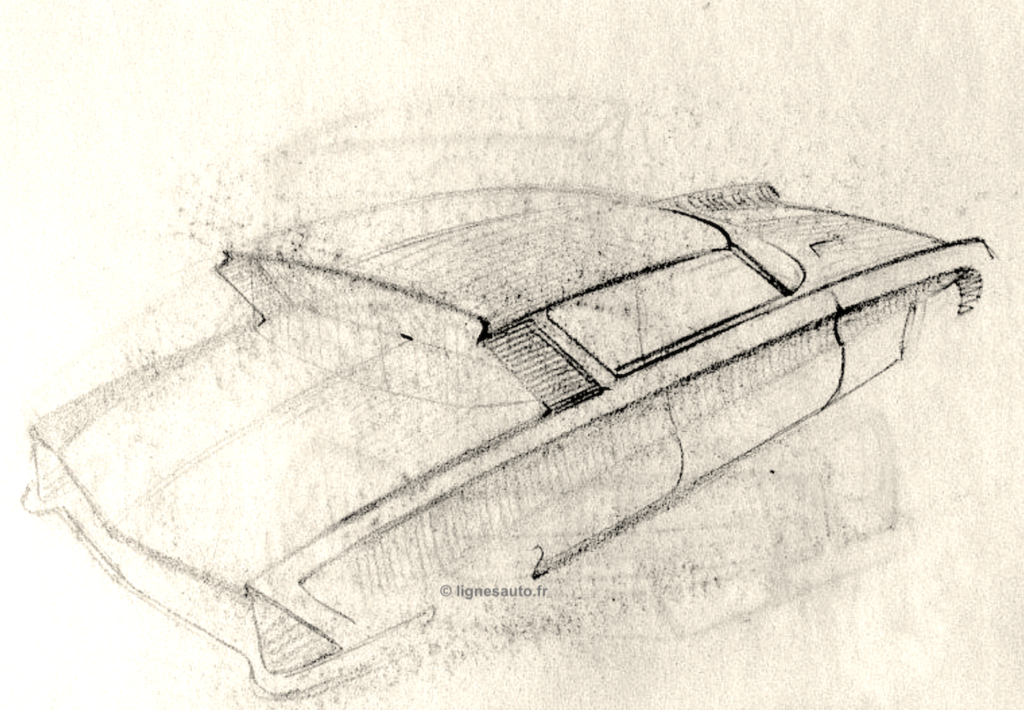

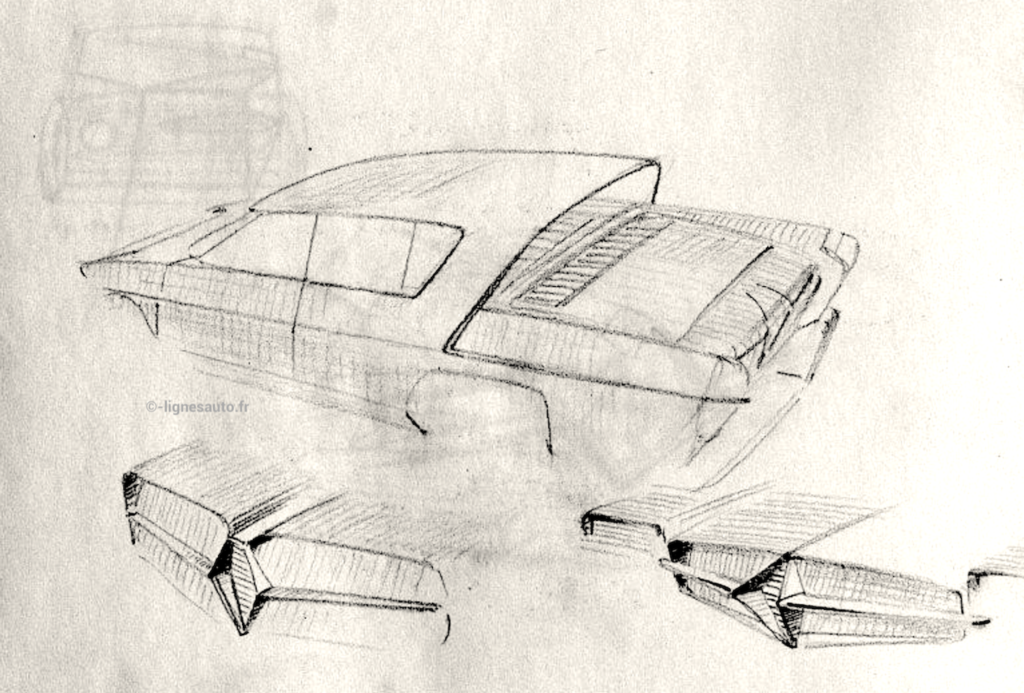

The famous “Z” line is well known in France thanks to Flaminio Bertoni’s Ami 6, although this was unveiled well after the Ford Anglia in our country. This Ford had already explored this stylistic theme. A theme that was obviously on (almost) every stylist’s mind, especially at Renault. At the end of the 1950s, Gaston Juchet was working on a 2-seater coupé above and a 2+2-seater below, in parallel with the Caravelle/Floride duo just launched on the market.

In addition to the above-mentioned integration of the Renault lozenge in the front grille (an approach that’s still relevant today, as demonstrated by the Emblème concept car), Gaston Juchet’s creation features a dynamic “Z”-shaped line at the rear, where the powertrain is housed, no doubt based on a Dauphine or the future 1962 R8. These sketches also show the well-integrated rear light clusters and the dynamic movement of the “Z” line extending over the rear wing.